This is the second part of a series on Ukraine’s historical association with Nazism. It is important to understand the history to be able to make sense of developments in the present. The story continues with Anglo-American recruitment of anti-Soviet collaborators.

US/UK Recruitment of Anti-Soviet Collaborators

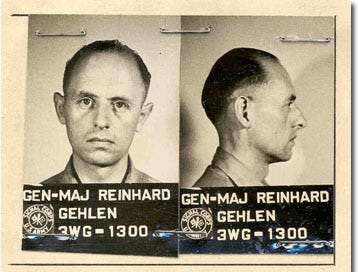

Office of Policy Coordination chief Frank Wisner sought to recreate SS underground networks in Eastern Europe, Byelorussia and Ukraine, to be activated in the event of a Soviet invasion of Europe (Loftus, 2011, pp. 80-81). To that end, he covertly made contact with senior ex-Nazis responsible for directing the activities of collaborators in Eastern Europe during World War II. These included Gustav Hilger, who worked with SS Intelligence late in the war to build an army of anticommunist collaborators; Friedrich Buchardt, SS head of Émigré Affairs and commander of Vorkommando Moskau; Gerhardt von Mende, head of the Caucasus division at the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territory; and Reinhard Gehlen, chief of the Wehrmacht Foreign Armies East military intelligence service. Through these contacts, Wisner was able to identify and recruit many leading Nazi collaborators in Eastern Europe, including Byelorussians Franz Kushel, Jury Sobolewsky, and Emanuel Jasiuk (Radoslaw Ostrowsky went to Argentina). He smuggled these fugitive war criminals to the United States to form “governments-in-exile,” misappropriating federal funds to purchase arms for them, and illegally providing shelter for them (Loftus, 2011, pp. 155, 194).

Gehlen surrendered himself, his staff, and his files to the U.S. Army, having avoided capture by the Soviets as a war criminal. Among the names of Nazi collaborators he produced were those of the Belarus Brigade who were hiding in refugee camps so as to evade war crimes investigators (Loftus, 2011, p. 82-83, 135-141). These included Ostrowsky, who was offered protection from prosecution for war crimes by the Americans in return for information collected from his network in the DP camps. Gehlen was interrogated in the United States, then sent back to Germany in July 1946 to head the U.S.-sponsored Organisation Gehlen, which included most of his wartime staff, ran the DP camps, and conducted espionage against the Soviet Union. Gehlen recommended that Franz Six, who had recruited Byelorussians for Operation Barbarossa, be hired to head the recruitment and training of the new Special Forces. The training was arranged by General Lucius Clay at the European Command Intelligence School near Oberammergau, with CIA funding for it being laundered through U.S. corporations (Loftus, 2011, p. 161).

Stanislaw Stankievich assisted the Nazis with the invasion of Byelorussia. Leading a police force of native volunteers, he massacred all 8,000 Jews in one town in a single day in 1941, ordering them to lie on top of each other in graves so that ammunition could be saved by shooting through two layers of Jews at a time; babies were buried alive to save bullets (Loftus, 2011, pp. 58-59). After the war, the State Department put Stankievich in charge of a refugee camp in the U.S. zone of occupation in Germany, where he was able to procure U.S. immigration visas for many of the Nazi collaborators with whom he had worked. Even when the U.S. Army Counter-Intelligence Corps (CIC) arrested and interrogated him, prompting a confession about his activities for the Nazis, the State Department had him released on the basis that he was an anti-communist organiser working for the British Secret Service. In 1946, Stankievich was placed in charge of an anti-communist propaganda organisation in Munich, and was later brought to the United States under his own name, given a job at Radio Liberty, and allowed to become a U.S. citizen (Loftus, 2011, p. 62).

The Gestapo-trained Mykola Lebed, whose SB (the Sluzhba Bezpeky, or secret police of the OUN/B) murdered tens of thousands of Poles, Jews and Ukrainians during the war, was referred to by the CIC as a “well-known sadist and collaborator of the Germans” (Dorrill, 2002, p. 236). That did not prevent the OPC, however, from using the SB in a postwar assassination programme against the Soviets codenamed REDWOOD (Loftus, 2011, p. 48). Allen Dulles in 1948 described Lebed as “of inestimable value to this Agency and its operations,” and the CIA engaged in operations for “the support, development, and exploitation of the Ukrainian underground movement for resistance and intelligence purposes” (cited in Breitman & Goda, 2010, p. 87). Under the CIA’s “100 Persons A Year Act,” which allowed entry into the United States for certain individuals who would otherwise be refused, Lebed was granted permanent US citizenship in 1949 by the DCI, with the approval of the Attorney General of the United States and the Commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, making him “arguably the highest-ranking Nazi war criminal ever to enter the United States” (Loftus, 2011, pp. 28, 39). Harry Rositzke, head of CIA covert operations against the Soviet Union, reflected: “It was a visceral business of using any bastard as long as he was anticommunist … [and] the eagerness or desire to enlist collaborators meant that sure, you didn’t look at their credentials too closely” (cited in Rossoliński-Liebe, 2014, p. 320).

Britain, through MI6, backed the Bandera/Stetsko faction of the OUN, which split from the Lebed/Hrinioch faction over whether there should be an ethnically homogenous, independent Ukraine led by Bandera as dictator. The Lebed/Hrinioch faction recognised the need to appeal to eastern Ukrainian nationalists of Russian descent. Stetsko was placed in charge of the Bloc of Anti-Bolshevik Nations (ABN), founded in 1946. In 1947, the Labour government of Clement Attlee secretly approved the repatriation of what remained of SS Galizien to Britain, i.e. 8,570 Ukrainian SS soldiers responsible for some of the worst atrocities of World War II (Goodman, 2000). In 1950, 2,000 of these men were sent to live in Canada, where they were joined by a further 1,000 SS men and Nazi collaborators from the Baltic states (Tugend, 1997). Other former Nazi-sponsored émigré assets were sent to South America, the United States, and Australia (Dorril, 2002, p. 240; Loftus, 2011, p. 60). Also that year, MI6 began training Bandera’s agents to provide intelligence from western Ukraine (Breitman & Goda, 2010, p. 81). Unbeknownst to MI6, however, double agent Kim Philby had been infiltrating right-wing exile groups, including the OUN, the Byelorussian Central Council, and the Russian NTS (National Alliance of Russian Solidarists) with Soviet agents (Loftus, 2011, p. 163), meaning that intelligence flowed both ways.

Rositzke concluded in early 1950 that the OUN/UPA guerillas could “play no serious paramilitary role” in the event of a Soviet attack on the West (cited in Dorril, 2002, p. 243), meaning that the guerillas were useful only for espionage purposes. The CIA’s AERODYNAMIC project, run by Lebed in New York to produce propaganda aimed at disaffected Ukrainian citizens, was formally incorporated as the non-profit Proloh (Prologue) Research and Publishing Association in 1956. Prologue was, according to CIA documentation, the sole “vehicle for CIA’s operations directed at the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and [its] forty million Ukrainian citizens” (cited in Breitman & Goda, 2010, p. 89).

Despite a secret visit by Bandera to Washington in 1950, the CIA warned MI6 against using him as an asset, noting that his Ukrainian support had declined markedly. Indeed, Bandera no longer had the support of the UHVR or the OUN leadership, and in 1951 he became stridently anti-American and worked against CIA Ukrainian agents, leading to the CIA’s desire to “politically neutralize” him (Breitman & Goda, 2010, pp. 81-82). With London finally breaking with him in 1954, he was left to create “an even smaller, more secret network” (Dorril, 2002, p. 247), notwithstanding a short-lived alliance with West German intelligence under Gehlen. Anglo-American intelligence officials were left to balance their desire to “quiet” Bandera with the need to make sure that the Soviets did not make a martyr out of him (Breitman & Goda, 2010, p. 83). CIA officials recommended in October 1959 that Bandera be granted the U.S. visa he had been trying to obtain since 1955, but ten days later he was dead, allegedly murdered by KGB assassin Bogdan Stashinskiy using a cyanide spray.

References

Breitman, R. & Goda, N.J.W. (2010). Hitler's shadow: Nazi war criminals, U.S. intelligence, and the Cold War. National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/files/iwg/reports/hitlers-shadow.pdf

Dorril, S. (2002). MI6: Inside the covert world of Her Majesty's secret intelligence service. Simon and Schuster.

Goodman, G. (2000, June 12). An unshown film. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2000/jun/12/freedomofinformation.uk

Loftus, J. (2011). America’s Nazi secret. Trine Day.

Rossoliński-Liebe, G. (2014). Stepan Bandera: The Life and Afterlife of a Ukrainian Nationalist. ibidem Press.

Tugend, T. (1997, February 7). Canada admits letting in 2,000 Ukrainian SS troopers. The Jewish News of Northern California. https://jweekly.com/1997/02/07/canada-admits-letting-in-2-000-ukrainian-ss-troopers/

Featured Image Credit: https://military-history.fandom.com/wiki/Reinhard_Gehlen?file=Reinhard_Gehlen_1945.jpg

After Stalin's artificial famine in the Ukraine, why would anyone greeting the Germans as "liberators" would be considered a war criminal? How about Katyn, when the Soviets massacred about 20 thousand Polish soldiers?

https://muzeum.szczecin.pl/en/exhibitions/temporary/1950-katyn-anniversary-of-the-crime.html

David, if you haven't already done so, I recommend this book: Weaponizing Anthropology: Social Science in Service of the Militarized State.