The Law vs. The Truth: Getting to the Bottom of the Richard D. Hall Case

Part 6 - Truth vs. Authority

Part 6 - Truth vs. Authority

Introduction

So far, this series has looked at some of the forensic evidence presented by Richard D. Hall, and later Iain Davis, in relation to the Manchester Arena incident of May 22, 2017. It has shown that all of that evidence was struck out from Hall’s defence by a Summary Judgment that was prejudiced, unreasonable, and unjust. It has demonstrated that not a single constitutive element of Hall’s conviction for harassment withstands scrutiny. And it has exonerated Hall of any abuse of media freedom.

This Part explores the ways in which legal appeals to authority have been used to close down critical inquiry into the Manchester Arena incident, thus suppressing the truth about what really took place.

The one thing that was never up for debate in Hall’s trial was what exactly occurred in the City Room on May 22, 2017. Instead, reality was decreed by a succession of High Court judges, so that the official version of events could not be challenged at trial.

Master Richard Davison in the Summary Judgment describes Hall’s “theory that the Manchester bombing was an operation staged by government agencies in which no one was genuinely killed or injured” as “absurd and fantastical” [25]. The idea that “the claimants were not there and were either not severely injured at all or acquired their injuries earlier and by a different mechanism than the bombing” is, for Davison, “simply preposterous” [37]. We saw in Part 3 why Davison’s findings lack any sound evidential foundation.

On April 15, 2024, Mrs. Justice Karen Steyn refused Hall’s application for permission to appeal Davison’s Summary Judgment, on the grounds that the conviction of Hashem Abedi had been “proved to the satisfaction of a jury, to the criminal standard” and that there was, therefore, “no real prospect of the appeal court concluding that Master Davison erred in his approach to s 11 of the Civil Evidence Act 1968.” Again, the flaws of relying on the Abedi conviction to establish what happened are laid out in Part 3.

On June 28, 2024, Mr. Justice Julian Knowles refused Hall’s renewed application for permission to appeal at an oral hearing, on the basis that the defendant’s evidence did “not come close to establishing any sort of case whatsoever” [36]. Knowles remarked that he would let the “ridiculous absurdity” of a section of Hall’s witness statement titled “summary of what I believe happened” “speak for itself” [37]. On what basis, then, did Knowles reach those conclusions?

Knowles’ Refusal of Hall’s Renewed Application to Appeal

Knowles refers to the Abedi trial and claims that it was “proved during the Saunders Inquiry” that “Salman Abedi blew himself up” [8]. As we saw in Part 3 , this is false. It was assumed, not proven, that Abedi blew himself up.

Knowles claims that Hall believes Abedi “was taken away from the Arena by the police” [8]. This, too, is false — as Knowles should have known, given that he cites Hall’s witness statement to the effect that Abedi “evaded the scene in a grey Audi vehicle, later being apprehended by regular police and subsequently cleared” [37]. Knowles’ ruling is, thus, sloppy.

Knowles states that he “did not really understand” Hall’s views regarding the potential motivation for staging the attack [8], yet two paragraphs later he cites Hall’s witness statement where those views could hardly be spelled out any more clearly or cogently:

Multiple motives underpin this orchestrated event. It served to tighten public control and facilitated the passing of legislation like Martyn’s Law. Furthermore, it bolstered security service budgets and justified heightened military actions in Libya. The incident also played into President Trump’s efforts to impose travel bans, particularly on Muslim-majority countries, bolstered by the narrative surrounding the Manchester incident.

Thus, it would appear that Knowles was feigning ignorance when claiming he “did not really understand” Hall’s views regarding possible motives for a staged attack.

Knowles finds Martin Hibbert’s witness statement plus his “corroborating evidence” (the Soni medical report) sufficient to demonstrate that Hibbert was at the concert. We saw in Part 3 why this is not the case.

Knowles refers to “much evidence given at the Inquiry about [the claimants’] presence and what happened to them. Mr Hibbert gave evidence to the Inquiry.” A video of Hibbert’s appearance before the Inquiry is indeed available, however, no accompanying evidence documents are (see the “Buried Evidence” section below). Hibbert’s sworn testimony to the Inquiry does not, by itself, prove that he was present at the concert.

Knowles finds that Section 11 of the Civil Evidence Act 1968 “was properly applied by [Davison] and by Steyn J. Its application here is so obvious as to require little explanation […]” [33]. Indeed, no explanation is given: Knowles simply repeats Davison’s position and agrees with it [34]. However, as we saw in Part 3, Davison’s application of Section 11 was highly selective and biased, especially in view of the evidence presented to him by Hall.

Thus, Knowles’ reasoning for refusing Hall’s renewed application for permission to appeal against the Summary Judgment proves to be sloppy, disingenuous, and biased towards Hibbert (whose word is accepted without question). Meanwhile, it amounts to little more than baseless condescension towards Hall.

Steyn’s Fallacious Appeal to Authority

In the Judgment, Steyn writes:

I have referred above to the various descriptions of the “ridiculous absurdity” of, and “far-fetched”, “absurd” “preposterous” and “fantastical” nature of, the narrative maintained by the defendant in this case, which have been given by the judges who considered his Defence earlier in these proceedings. Those epithets are apt […] [25].

Here, Steyn makes a fallacious appeal to authority. The fact that three senior High Court officials (Davison, Knowles, and Steyn) all agree that those insults are appropriate says absolutely nothing about the truth of the matter.

Steyn claims to have read or listened to “36 media files, 32 of which are video or audio files, and the remaining four are articles by Iain Davis” [30]. These include “the 2018 Video, the 2019 Video, the Film, the Statement Analysis Video, and the 2020 Video,” as well as the Book (see [11] for details). It is, therefore, impossible that she is unfamiliar with the evidence presented by Hall and Davis in relation to the Manchester Arena incident. Nevertheless, while describing some of it, she rejects the validity of all of it. Although this is her legal prerogative following Knowles’ ruling, to the hypothetical reasonable observer it may appear as unfair, unjust, and dishonest.

The fallacious appeal to authority is indeed the red thread in the Judgment. For example:

Mr Hall’s approach was to treat the statements of numerous ordinary people and professionals, including Mr Hibbert’s surgeon, as well as of an independent panel, and figures in authority, as of no value [188].

This is misleading. More accurate would be to claim that Hall finds such statements to be questionable or false, because they contradict primary empirical evidence, and that appealing to authority is fallacious when it comes to establishing the empirically verifiable truth. Hall’s primary evidence was excluded from the trial, however.

Steyn repeats the fallacy that Hashem Abedi’s conviction evidences “the facts that demonstrated the jury found proved to the criminal standard” [188]. This does not even make grammatical sense. Assuming it should read “the facts that the jury found proved to the criminal standard,” this tells us almost nothing concerning what empirically took place in the City Room on May 22, 2017 (see Part 3).

Prosecution barrister Price claimed in court that Hall’s behaviour was “dogmatic and unreasonable” and that Hall was “not able to accept the repeated judicial assertions.” But why should Hall accept repeated judicial assertions that dogmatically and unreasonably refuse to look at primary forensic evidence?

In the Judgment, Steyn laments that Hall shows no signs of abating in his heresy:

Since he first published each of the publications complained of, the Sentencing Remarks have been given, the Inquiry has reported, the inquests have occurred, and Mr Hall has obtained further information during these proceedings, yet he continues to publish them. [197(g)]

As was established in Part 3, the Sentencing Remarks in the Hashem Abedi trial tell us nothing useful about what took place in the City Room on May 22, 2017; they merely assume the official version of events is true.

The Inquiry will be dealt with at length below.

The inquests were originally to be conducted by Sir John Saunders, a retired High Court Judge, however, on October 22, 2019, they were rolled into the Inquiry, chaired by the same individual [131]. In Volume 2.2 of the Inquiry report, Saunders prefaces section 18 (“Fatal Consequences of the Explosion”) by stating “This is the information that, as a Coroner, I would have included in the record of inquest for each person” [18.5, my emphasis]. This is a tacit admission that formal inquests for each death were not concluded. Therefore, Steyn is being deliberately misleading when claiming that “the inquests have occurred” [197(g)]. They began but were never finished: there are no coroner’s reports.

How Does Steyn Know What Took Place in the City Room?

The opening paragraph of the Judgment draws on the inadequately evidenced findings of the Summary Judgment to assert:

On 22 May 2017, a terrorist caused a bomb to explode at the Manchester Arena, at the conclusion of a concert performed by Ariana Grande, murdering 22 people, injuring many others, and killing himself (‘the Manchester Arena attack’ or ‘the Attack’). The claimants, Martin Hibbert, and his daughter Eve, had attended the concert, and each suffered grave, life-changing injuries in the Attack. [1]

The second paragraph begins:

This case concerns a false narrative, published by the defendant, an independent journalist and broadcaster, that the Manchester Arena attack was an elaborate hoax — carefully planned by elements within the state and involving ordinary citizens (including the claimants) in the deception as “crisis actors” — in which no one was injured or died. [2]

Thus, the case has, for all intents and purposes, been resolved in favour of the claimants within the first three sentences of the Judgment: they are telling the truth, and Hall’s position is “false.”

Yet, how does Steyn know what took place in the City Room on May 22, 2017? On the one and only occasion when she tries to interpret primary empirical evidence for herself, it becomes painfully clear that she has no idea, empirically, what she is looking at. She finds that, in the 2018 Video, Hall

shows a photograph of the aftermath of the Attack, after paramedics had arrived and bodies of those [who] were killed had been removed, and compares it with video footage of an obviously staged bombing, said to be in Iraq, in which a car explodes and then several people run from out of shot to lie down and pretend to be injured. [53, my emphasis]

Here, Steyn is claiming that the Parker photograph was taken after paramedics had arrived and after bodies had been removed.

The Parker photograph. Source: Hall (2020, p. 26).

Yet, we know from Davis’ analysis that the Parker photograph was taken while the Barr footage was being filmed (four minutes after the bang, according to Barr, i.e. at 22:35), and that this was well before any bodies were removed from the foyer (beginning at 22:58, according to the Kerslake Report, pp. 59-60).

Pace Steyn, it is demonstrably not the case that “paramedics had arrived” [53]. The Parker photograph shows Showsec security staff (in yellow), plus TravelSafe staff from Manchester Victoria Station (in high visibility jackets) and Emergency Training UK (ETUK) staff in green (who provided first aid services at the concert), but no paramedics, who had not yet arrived.

Therefore, Steyn has taken liberties by imposing her own, false interpretation of events onto the evidence, while accusing Hall of presenting a “false narrative” [2]. This is unbecoming of a High Court judge, whose role is to deliver justice impartially. It goes to show how ridiculous it is for the judiciary to appoint themselves as arbiters of truth, when they cannot perform basic assessments of empirical evidence.

Suppression of Key Evidence by the Court

The Judgment against Hall relies on burying the truth to the maximum extent possible. One obvious indicator of this is the Court’s deliberate suppression of key evidence. In this context, Steyn finds that Hall

would be open to modifying his opinion if he were shown evidence such as the unredacted CCTV of what occurred at the Manchester Arena on 22 May 2017 and the full medical records of the claimants. His inability to comprehend why sensitive and graphic images of the deceased and seriously injured would not be shown to the general public, or to understand why Eve’s parents would be at pains to keep their daughter out of the public eye (which the Inquiry respected by not releasing footage of the claimants at the Arena), or to understand the claimants’ wish to maintain privacy in respect of their medical records (save to the limited extent that they have disclosed two reports) does not detract from my conclusion [...] [180]

Let us, then, consider the CCTV and medical evidence in question.

CCTV Evidence

The Judgment notes that

Mr Hibbert gave evidence [to the Inquiry] that there are photographs contained in his “Sequence of Events” put together by Greater Manchester Police for the Inquiry that show him and Eve entering the City Room at 20:03 and re-entering the City Room at 22:30:53 after the concert, just before the explosion. [19]

Both images would not have shown “graphic images of the deceased and seriously injured” [180], because both precede the detonation time, i.e., 22:31:00. However, the 22:30:53 image, coming just seven seconds before detonation, would show most, if not all, of the deceased in their final moments of life, and so could perhaps be deemed too sensitive for public release.

The 20:03 image, on the other hand, would have been captured nearly two and a half hours earlier, showing nothing more than some random people in the City Room, including the claimants. Why, then, has that image not been released? Hall made this point in his trial: “because this was at 8.00pm, hours before the alleged bomb, there is no reason why those images should not be in [...] the available section of the public [i]nquiry files.” There is no mention of this in the Judgment, however.

Better still, why not make public the CCTV footage showing the claimants walking through the City Room at 20:03? Assuming its authenticity could be verified, that would remove all doubt that the claimants were actually at the Manchester Arena that night.

As things stand, Hall has raised a troubling point, namely, that there is no irrefutable, publicly available evidence that the claimants were in fact present at the Manchester Arena on the night in question. For example, there were 14,000 concert-goers, the vast majority of whom would have had camera phones, yet not a single publicly available photograph (e.g. posted to social media) shows the claimants. The Saunders Inquiry released 806 CCTV images, showing hundreds of different people in many different areas, but not the claimants. The claimants are not identifiable in the Barr footage or the Parker photograph (see Part 2). They do not feature in other people’s witness statements. Absence of evidence may not be evidence of absence, but it is certainly enough to raise suspicion.

Given that providing irrefutable evidence of their presence at the Arena that night would have greatly bolstered their case, we have to ask why the 20:03 photograph was not shown to the Court at Hall’s request and why, instead, we are expected to take the word of Terry Wilcox that it exists, when Wilcox is a Manager at Hudgell Solicitors, the firm that represented the claimants (see Part 3)? Steyn accepts Wilcox’s “confirmation” that the Hibberts were “viewed on the CCTV pre- and post-detonation” [20] just as uncritically as Davison does in the Summary Judgment, ignoring the glaring conflict of interest involved.

Steyn claims that “Eve’s parents [were] at pains to keep their daughter out of the public eye,” and that the Saunders Inquiry respected this “by not releasing footage of the claimants at the Arena” [180]. But where is the evidence for this? For example, is there any evidence of Eve’s parents petitioning the Inquiry to block the release of footage showing the claimants? None is provided in the Judgment, nor was this mentioned when Hibbert gave evidence to the Inquiry.

Many of the CCTV footage images released by the Inquiry show scores of people milling around. It requires very hard work, of the kind that took Hall “about three months,” to look at every individual on all 806 images, and it seems unlikely that the Inquiry would have done so. Besides, had the claimants featured as two small figures among many on a CCTV image, that would hardly have counted as being in the “public eye.”

Medical Evidence

Prosecution barrister Price cited Hall’s witness statement in the trial:

According to Martin Hibbert, his daughter, Eve, suffered a single head injury from a bolt entering on one side and exiting the other side of her head, resulting in the loss of function in her left arm and leg. This suggests a totally catastrophic level of injury. However, this account given by Martin Hibbert entirely lacks medical documentation, medical imaging, scans, or even any images supporting the claimed injury caused by a bolt travelling at 90 miles an hour.

Instead of challenging Hall’s contention by providing even a single piece of medical documentation that would refute it, Price merely asked “Why do you not just believe Martin, Sarah, and Eve?”

Price appealed to the evidence provided by Hibbert’s consultant, BM Soni, in 2020, which is discussed in Part 3. We now learn that Soni wrote the following:

The initial referral information which was uploaded on the web, referral page on 23 May, stated: ‘Admitted to A&E 23 May 2017, 01.44 hours. Multiple penetrating injury.’

Yet, according to evidence given by Hibbert to the Saunders Inquiry, cited by Price in his opening remarks,

Martin Hibbert was taken out of the City Room at 23.21. Eve was taken out at 23.25. They were both taken to the Casualty Clearing Station. Eve left by ambulance at 00.18. He found it ‘baffling’ that she was not put straight into an ambulance. In those circumstances, he thought it was a miracle that she was still alive. He said he had ‘just no words for it’. Martin Hibbert left for hospital at 00.24, 1 hour and 53 minutes after the detonation. When he was placed in an ambulance, he was going to be taken to Wythenshawe Hospital. This was a 25- to 30-minute journey. The paramedic, however, went to Salford Royal Hospital, 10 minutes’ away. Martin Hibbert said that decision was ‘life saving.’

So, according to Hibbert, he left for hospital at 00:24, which was 10 minutes away. That places his arrival at the hospital at or around 00:34, which is an hour and ten minutes before the time given by Soni. Sophie Cartwright QC specified precisely during the Inquiry hearings that Hibbert arrived at hospital eight minutes after departure at 00:32:07, not 01:44. What explains that rather large (72-minute) discrepancy? Either Soni’s report, or Hibbert’s version of events, or both, must be wrong.

There followed an exchange between Price and Hall:

Mr Price: Now what that means is that Mr Sodhi [sic.], who is a surgeon, with no skin in the game, one would not have thought, had accessed A&E and/or paramedic records about Martin, and about Martin’s admission. And you are going to tell me that somewhere along the line someone’s invented something?

Mr Hall: Well, how do you know he has accessed them?

Mr Price: Because he says he has. He, he is relying on them.

Mr Hall: Ah, because he says he has?

Mr Price: Yes, I, I am relying on a signed witness statement by Mr Sodhi.

Mr Hall: Right. Well, I am saying that witnesses sometimes do not tell the truth.

Mr Price: Yeah. You think Mr Sodhi is lying?

Mr Hall: It would be far simpler for you to just [...] produce the medical records that he is referring to, rather than a report written three years after the events, which prove nothing. They do not prove presence at the concert.

Hall has a point. From what little we know about Soni’s evidence, it appears unreliable, because the A&E admission time does not make sense. Not only does it not match Hibbert’s evidence to the Inquiry, but it means that it took three hours and 13 minutes to get two of the most seriously injured victims — one with a bolt having passed through her head, the other having suffered 22 shrapnel wounds — to a hospital ten minutes away. Therefore, there is no reason to trust the validity of Soni’s report, let alone accept it as sufficient medical evidence regarding the causation of Martin Hibbert’s injuries. At the summary judgment hearing, Hall testified under oath, and was not challenged by the Prosecution, that the information contained in Soni’s report “does not provide evidence of the time and place when the Claimants suffered the injuries.”

Defence barrister Oakley cross-examined Hibbert on the lack of medical evidence regarding his and Eve’s alleged trauma:

Mr Oakley: If you are bringing a claim in court and you are alleging that you have suffered psychological trauma, in order to establish that you have to produce a medical report, and I am putting to you that there is no such medical report produced for the purpose of these court proceedings to say that either you or Eve had suffered from psychological trauma.

Mr Hibbert: “Not separately towards this, but obviously there are, you know, lots of medical, you know, data in my file but not conclusive to this, no.”

So, again, no primary medical evidence was adduced in the trial to support the claimants’ contentions regarding their injuries and suffering. Hibbert’s admission that he and Eve had no medical evidence of having sustained trauma as a result of whatever took place in the City Room on May 22, 2017, does not feature in the Judgment.

Steyn’s finding that “the claimants’ wish to maintain privacy in respect of their medical records (save to the limited extent that they have disclosed two reports)” [180] starkly contradicts Martin Hibbert’s book, serialised in the Daily Mail between April 20-22, 2024, in which he writes about seeing the “horrifying hole around her [Eve’s] right temple exposing brain tissue.” Further graphic details from Hibbert’s book are provided in Part 5.

In the trial, Hall cited orthopaedic surgeon Dr David Halpin, who examined the alleged X-ray of Hibbert published in LADbible in 2018:

Mr Hall: […] Dr David Halpin, who is an orthopaedic surgeon, […] looked at that X-ray image and said that […] the person in the image has no teeth. And he recommended that an expert dental witness look at that X-ray, whether to confirm this or not. Dr Halpin commented that there are photographs of Martin Hibbert in the media appearing to show that he does have a full set of teeth.

That evidence too, is omitted from the Judgment, presumably because Davison had already ruled in the Summary Judgment: “The witness statement of Mr Halpin FRCS (consisting of his observations on one x ray and one image of Mr Hibbert) does not take matters any further and does not contradict the claimants’ evidence” [38(iii)].

Why did the claimants not enter that X-ray into evidence? After all, it supposedly shows Hibbert’s injuries and would count as primary evidence if its authenticity could be verified. The fact that it was not entered into evidence, coupled with the discrepancies between what it shows and what Hibbert claimed about his injuries in LADbible (see Part 3), suggests it does not meet the evidential standards required for a trial and is probably fake. If it is fake, why did Hibbert agree to its publication? Such considerations do not arise in the Judgment.

How Can a Trial be Fair if One Side is not Allowed to Present Key Evidence?

With primary empirical evidence systematically excluded from the trial because of the pre-trial rulings, Steyn, in the Judgment, is free to assert “the central facts that a suicide bomber detonated a home-made bomb (surrounding the explosive material with nuts and bolts), killing 22 innocent people and himself, and injuring many others, including inflicting life-changing injuries on Mr Hibbert and his daughter” [182]. All of the forensic evidence summarised in Part 2, and explored in greater detail in Hall’s work and that of Iain Davis (which was entered into evidence), gets buried. No serious thinker can accept this modus operandi as valid.

While the Prosecution was not required to produce any irrefutable evidence of the claimants’ presence at the Manchester Arena on May 22, 2017, Hall was not allowed to present his key evidence at the trial. As Hall told Davison during the summary judgment hearing:

How could a trial possibly be a fair trial if I am not allowed to present the evidence which proves that my opinions are honestly held? It is grossly assumptive and wrong to suggest that my evidence would have no chance of success at a trial [...]. The evidence I have is solid. It is evidence which passes the test of suitability of any sort of trial and it is here in this [80-page] document for the public record.

The double standards on display were glaring. As Hall highlighted,

We are in a situation where the Claimants have not produced the evidence requested by me to establish that their claim is not true, yet at the same time they are applying to have my evidence excluded from a trial, which I believe shows that their claims may not be true.

Incredibly, the claimants somehow got away with producing no publicly available evidence to corroborate their claims, while ensuring that Hall’s publicly available evidence was rendered inadmissible at trial.

The Saunders Inquiry

The public inquiry into the Manchester Arena incident, chaired by former High Court judge, Sir John Saunders (“the Inquiry”), is cited as authoritative multiple times in the Judgment [4, 12, 16, 19, 25, 131-135, 180, 197, 206-207].

Hall told Davison that he had “spent years” sifting through 1,300 hours of footage from the Inquiry. As a result of his painstaking investigation, he found the Inquiry “at the very least, badly flawed.” Not only were there “extremely worrying omissions” of certain evidence, but, in Hall’s view, the Inquiry actively sought to mislead the public.

Hall condensed his key findings regarding the Inquiry into an 82-minute film titled Manchester on Trial (2023), which you can watch below.

Richard D. Hall, Manchester on Trial

Why Trust the Inquiry?

Hall in his skeleton argument for the summary judgment hearing set out the following generic reasons for scepticism:

Public inquiries are not trials. Public inquiries are initiated and funded by the Government and are tasked with providing recommendations to the Government so the Government can then set policies. Therefore, the purpose of a public inquiry is a political exercise. They do not have the same legal standing as a trial. In a public inquiry, one counsel asks all the questions. There is no mandate in a public inquiry to test or challenge each piece of evidence. Therefore, any findings of a public inquiry have not satisfied the burden of proof which would be expected in a trial. Merely by referring to the findings of a public inquiry to support a claim is wholly unacceptable.

Hall also made reference to the track record of flawed public inquiries in the UK, including the Widgery Tribunal, which “lied about the facts of Bloody Sunday, in order to exculpate the actions of the British Army, who shot and killed unarmed members of the public,” and the Hillsborough disaster of 1989, when it was found eight years later that “South Yorkshire Police changed 164 officers’ accounts of the disaster before sending them to the Taylor Inquiry.”

Hall noted that Janet Senior had told the Manchester Arena inquiry that police had continually changed her statements, which she consequently refused to sign, and asked how widespread that practice might have been.

Notwithstanding Hall’s reasons for scepticism, Steyn defers to Knowles’ claim that “The Inquiry’s Report is a multi-volume, meticulously detailed analysis of what happened that night, as well as many other matters touching upon the Bombing” [134]. This automatic acceptance of the Inquiry’s findings does indeed look more like a political exercise than a legal one.

Hall stated during the trial:

I would ask Julian Knowles whether he has read my book, and whether he has watched the eight hours of film that I have produced, and also read my full 100 […] page evidence document.

Given that Knowles, in his ruling, could not even get basic facts right regarding Hall’s claims, it is highly likely that Knowles has only minimal familiarity with Hall’s work — despite his central role in making sure that Hall could not present his main evidence at trial.

As point of fact, the Inquiry was not meticulous. As Davis observes,

Just like the High Court, the Inquiry completely ignored the Bickerstaff video, the Barr footage, and the police audio recordings — Abedi’s lower body was vaguely placed “near to the seat of the explosion” and his torso somewhere “close to the arena box office” or thereabouts. Contradictory witness accounts were brushed aside or left unexplored and the alleged “point of blast image” [see Part 2] was conspicuous only for its absence. No crime scene photographs, autopsy reports or CCTV evidence showing any fatalities or injuries were entered into evidence.

Five months before the Inquiry hearings began (on September 7, 2020), Hall wrote to the Inquiry (on April 2, 2020, less than a week after his book was published), enclosing five copies of the book for the assistance of Saunders and Counsel [132-133]. However, the Inquiry failed to consider the key evidence presented in Hall’s book (as laid out in Parts 2 and 3). Thus, once again, we find key evidence being suppressed.

Ongoing Suppression of Inquiry Evidence

It is incumbent upon the chairperson of a public inquiry in the UK to make the evidence and documents given at the inquiry publicly available. According to the Public Inquiries Act (2005), section 18,

(1) Subject to any restrictions imposed by a notice or order under section 19, the chairman must take such steps as he considers reasonable to secure that members of the public (including reporters) are able —

[…] (b) to obtain or to view a record of evidence and documents given, produced or provided to the inquiry or inquiry panel.

The Manchester Arena Inquiry hearings concluded in March 2022 [133]. The third and final volume of the Inquiry report was published in March 2023 [134]. Yet, in 2024, it is remarkably hard for the public to find the evidence and documents presented to the Inquiry.

The original Inquiry website (https://manchesterarenainquiry.org.uk), to which all the footnotes in the Inquiry reports link, is no longer active. One instead has to go to the National Archives website for information. Only after undertaking a convoluted, time-consuming, and counter-intuitive navigation of that website did one anonymous commentator manage to find a page titled Evidence, which features 177 results. Even then, however, searching the evidence by witness returns broken links, and the red search bar at the top of the page, which is for the entire National Archives site rather than just the Manchester Arena Inquiry, proves more useful.

When the anonymous commentator pointed out these problems to the Home Office in April 2024, the problem was not resolved.

Evidence Given by Martin Hibbert

Searching for Martin Hibbert on the National Archives website reveals that he gave evidence on July 22, 2021, yet clicking on the “View Evidence” button returns “No evidence brought up in court.” Unlike for every other day of the Inquiry, no documents are downloadable. Why not?

The plot thickens when one views the National Archives evidence chronologically:

For some reason, the day when Hibbert gave evidence is the only day that appears chronologically out of order. Why is this?

The Inquiry’s YouTube channel, which at first glance appears to contain complete footage of each day’s proceedings, omits July 22, 2021, when Hibbert gave evidence, from its “Videos” section (although it can be found in the “Live” section). The morning and afternoon sessions for that date can be found here and here. Hibbert gives evidence between between 32:50 and 1:20:00 in the video for the morning session. The transcript for Hibbert’s testimony (which was very difficult to locate) can be found on the National Archives website here.

The morning session of the Inquiry on July 22, 2021, when Martin Hibbert gave evidence.

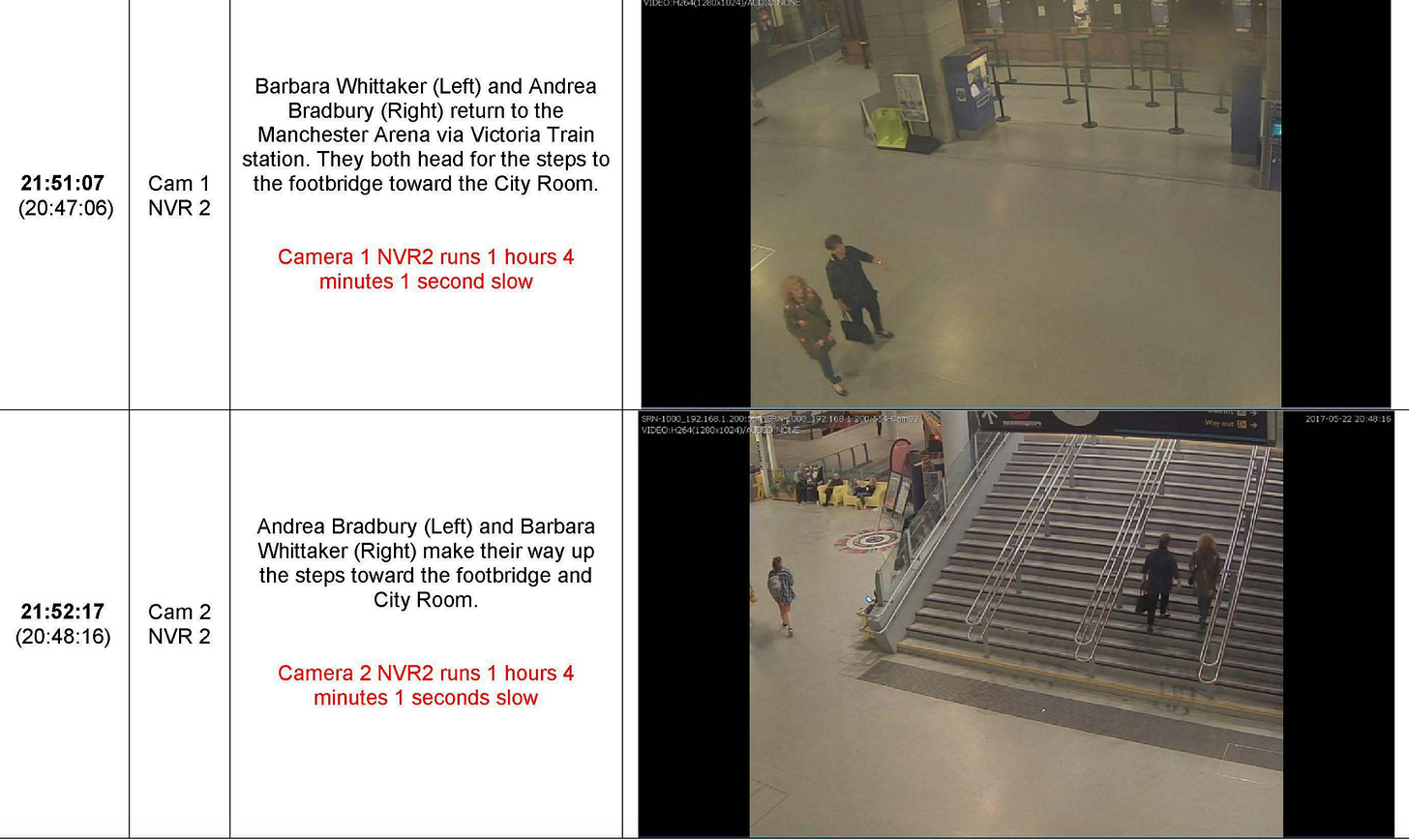

In contrast, the evidence given by Andrea Bradbury, Janet Senior, and Josephine Howarth (all classed as survivors, like Hibbert) includes a variety of documents, including CCTV images in the case of Bradbury:

Given that CCTV imagery showing Andrea Bradbury in the City Room a significant time before the blast is publicly available, why is the same not true of the claimants?

Other Missing Evidence

Much of the evidence that is provided on the National Archives website in relation to the Manchester Arena Inquiry is incomplete. For example, many witness statements include just the first page, viz. this one by Showsec Managing Director Mark Harding. The “Statement” by Suzanne Atkins, who was classed as a survivor, only includes a map placing her next to the completely undamaged merchandise stall at the moment of detonation; the statement itself is missing.

Does the missing evidence have to do with restriction orders placed in accordance with section 19 of the Public Inquiries Act (2005), which, according to subsection 5(b) can be imposed for reasons of “national security,” among other things? We know that certain restriction orders were made by doing an online search for “Manchester Arena Inquiry” and “Restriction Orders.” The following results come up:

From these results we know that “operationally sensitive content” shown to “core participants” was not disclosed to the public, and that Greater Manchester Police applied for at least one restriction order. Presumably, “operationally sensitive” refers to Operation Manteline, the GMP investigation into the Manchester Arena incident.

It would be interesting to know which content was deemed “operationally sensitive” and why. For example, the 20:03 and 22:30:53 CCTV images that Hibbert claimed GMP had shown to him appear to fall in that category:

Mr Hall: Now, at the public inquiry, these images were not shown, right? It was stated at the public inquiry that the Claimant had been shown the images but no image was present, so Sophie Cartwright [QC, counsel to Sir John Saunders] stood up and said:

“Mr Hibbert, you have been shown these images.”

So what is the point of a public inquiry doing that, showing, showing the victim images in private? Surely a public inquiry is for the evidence to be shown to the public, not something […] that the witness is already aware of.

What makes the 20:03 CCTV image in particular “operationally sensitive”? Is it because it does not exist? What exactly is the nature of the operation: to investigate what happened, or to cover it up? There seems to be no good reason why the 20:03 image has not been made publicly available.

Because mancheseterarenainquiry.org.uk is defunct, and because there appears to be nothing about restriction orders in relation to the Inquiry on the National Archives website, the public cannot find out anything more about the restriction orders that were made.

Did the Inquiry Seek to Mislead the Public?

At the summary judgment hearing, Hall claimed to have uncovered “evidence that the inquiry attempted to mislead the public about the facts and the evidence.” This relates primarily to CCTV footage, police radio communications, and the type of device detonated.

CCTV Images

A primary example relates to the CCTV still image which is time-stamped 22:30:59, i.e., one second before detonation:

We saw in Part 2 why this image is inconsistent with the Barr footage and the Parker photograph, which were taken approximately four minutes later and do not show anywhere near the number of bodies, body parts, blood, etc., that one would expect to see had a massive TATP shrapnel bomb just gone off in the middle of the room.

Hall contends that the above image was, in fact, captured “30 seconds before the blast,” and that “they have covered some activity up in the 30 seconds leading up to the blast, which I suspect is a preparation for the drill.” For example, we know from two witness testimonies that the doors to the concourse were sealed off by Showsec personnel shortly before the bang (07:55-09:10). In contrast, Volume 1 of the Inquiry report states that “Eleven of those who were killed came through the Arena concourse doors into the City Room after 22:30.” There is an obvious tension that needs to be resolved.

There were three CCTV cameras in the City Room, two fixed, one moveable. Hall observes that the Inquiry did not show moving CCTV footage from any of them leading up to the blast. Doubtless this will be attributed to sensitivity to the victims and their families, but it does mean that vital evidence that would definitively clear up what was taking place in the City Room at the key time has not been shown to the public.

Although Volume 1 of the Inquiry report (§1.6 and §1.24) mentions that Abedi was in a CCTV blind spot, the Inquiry did not map the CCTV blind spots, as Hall did below. Note that the merchandise stall is in a CCTV blind spot: were it not for the Barr footage, there would have been no evidence of it surviving undamaged.

C = camera spot, the blue lines mark out each camera’s field of vision, green = CCTV blind spot. Source: Hall, Manchester on Trial (03:20).

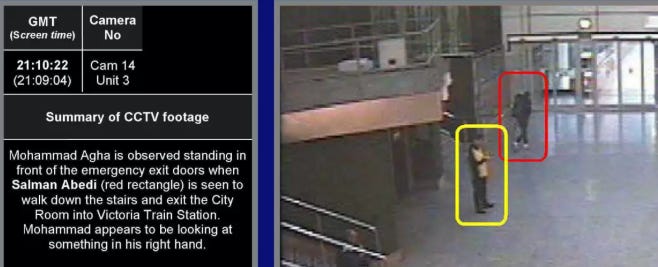

The Inquiry’s failure to map the CCTV blind spots is especially important when it comes to the movements of Salman Abedi. We know from CCTV evidence as well as witness testimony at the Inquiry (see below) that Abedi entered the City Room carrying a large rucksack around 20:51:40, left again around 21:10:22, and returned around 21:33:13 before heading up the stairs next to MacDonald’s:

Source: Richplanet.net.

As shown below, the top of those stairs places Abedi in a CCTV blind spot (compare with the diagram above):

Source: Hall, Manchester on Trial

The cross marks Abedi’s location at 22:12, according to Volume 1 of the Inquiry report (Figure 3).

That said, the CCTV camera near the merchandise stall was moveable, and 21:43:30, its operator pointed it in the direction of the McDonald’s steps. Note the Inquiry’s accompanying comment on the image, namely, that “Salman Abedi is not observed on the upper Mezzanine level”:

Source: Richplanet.net.

Abedi was then not captured in a publicly disclosed CCTV image again until 22:30, when he crossed the City Room with a rucksack on his back (see Part 2). As Hall and Davis have argued (see Part 2), there is good evidence to suggest that Abedi deposited his rucksack directly below the CCTV camera near the merchandise stall, which is in another CCTV blind spot, before running off.

Therefore, it is notable that most of Abedi’s key activity in the City Room took place in CCTV blind spots. Either this is an astonishing coincidence, or, if non-coincidental, does not comport with the idea of a suicide bomber who presumably would not have cared who saw what.

From witness testimony given to the Inquiry, Hall deduces that it was possible to establish the following with respect to Abedi’s movements:

Source: Hall, Manchester on Trial (04:44).

Note that once Abedi was in position at the top of the stairs, he was identified in seven witness testimonies covering a half hour period. On average, he was spotted just over once every four minutes. Yet, between 21:33 and 21:52, a 19-minute period confirmed by the 21:43:30 CCTV image, he was not seen at all, and does not appear on publicly available CCTV, strongly suggesting that he was not present in the City Room.

The “five SMG staff members from merchandising in the foyer” (p. 106), who from the merchandise stall would have had a direct line of sight up the McDonald’s steps to Abedi’s location all night long, were not called to give evidence at the Inquiry.

Police Radio Communications

At the summary judgment hearing, Hall told Davison that a whistle blower concerned about the police investigation had sent him a USB memory stick containing a copy of police radio communications from some time between 21:30 and 22:30 on the night in question. Listen to the key sections for yourself in Manchester — The Night of the Bang (19:20-23:26), or in full here. Hall was able to confirm the authenticity of the recordings, because certain sections were played at the Inquiry and were identical to his copy.

Damningly, Hall told Davison, the Inquiry neglected to play the most important sections of the recordings, thereby “covering up critical evidence which may have been able to prove that the alleged terrorist fled the scene.” In particular,

The recordings reveal that a member of the public reported to the police that, shortly before the explosion, an Asian male got out of a grey Audi vehicle [licence plate FV05 OPO] next to the arena, got a rucksack on to his back and then ran towards the arena.

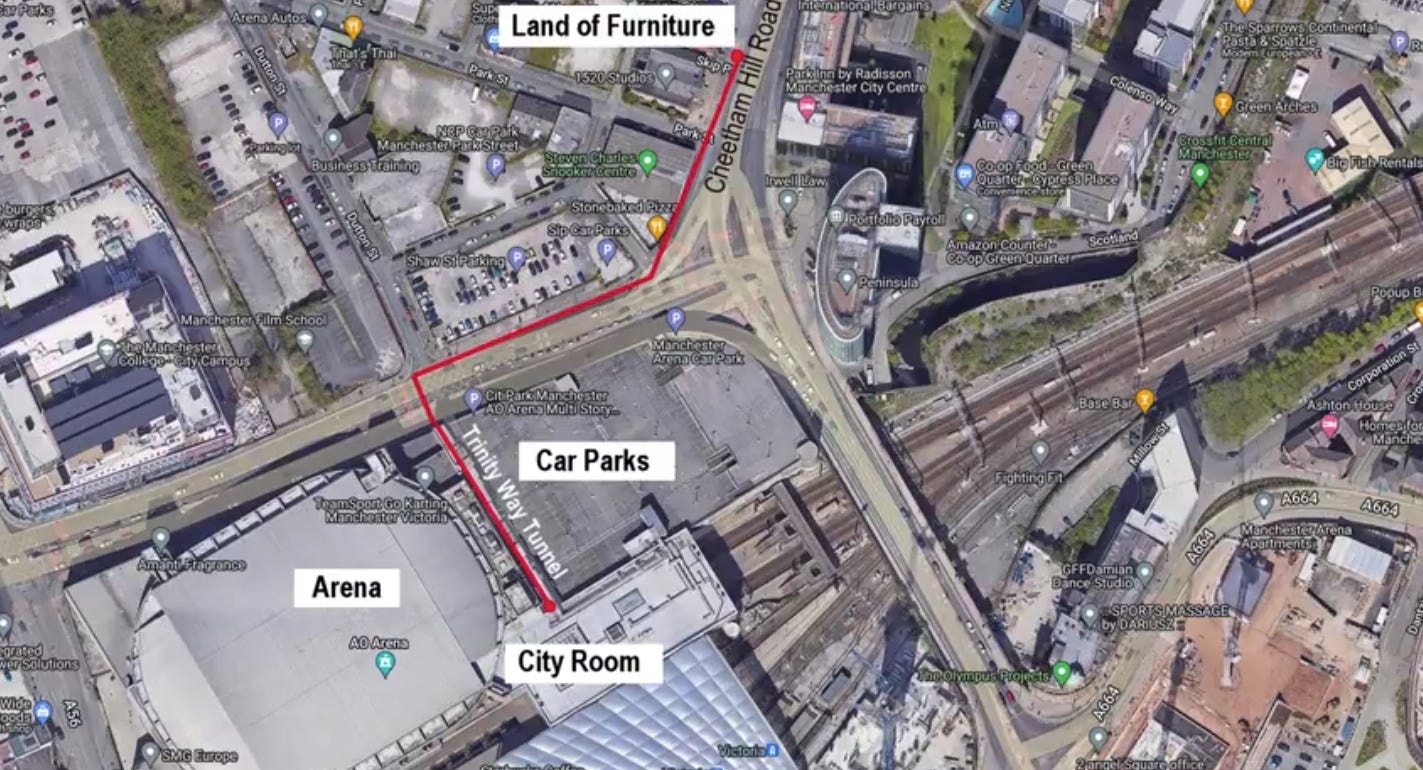

The vehicle was parked next to Land of Furniture on Cheetham Hill Road, only 250 metres away from the foyer and easily accessible via the Trinity Way tunnel:

Source: Hall, Manchester on Trial.

Hall proposes that between 21:33 and 21:52 (a time period that is consistent with both police radio communications and evidence from the City Room), Abedi left the City Room, fetched a grey Audi (most likely from the Arena car park), parked it illegally outside Land of Furniture, and then returned with his rucksack to his hiding place at the top of the stairs near MacDonald’s.

To reiterate, police radio communications recorded some time between 21:30 and 22:30 on May 22, 2017, unmistakably indicated that an Asian male illegally parked a grey Audi 250 metres from the City Room, and then ran with a rucksack on his back in the direction of the Arena. The Inquiry neglected to mention this obviously critical piece of evidence.

The illegally parked grey Audi not was a minor incident. As the police radio communications reveal, it was parked opposite a hotel, and police advised the manager to stop anyone from leaving while trying to get everyone away from the windows facing the vehicle. The surrounding area was to be sealed off. The Audi was eventually driven away, however, and the police pursued their “possible suspect” (01:16:53) for a considerable distance. As Hall goes on to show, this may even have culminated an armed arrest (22:15).

Source: Hall (2020, p. 17)

None of this evidence, which the Inquiry had at its disposal, was made public. The closest it came to appearing in the Inquiry was when Paul Greaney QC summarised various points, omitting any mention of the grey Audi, and Inspector Dale Sexton, the Force duty officer who directed operations from the control room, added “and a person in an Audi car.” To which Greaney replied “And a person in an Audi car. But that was quite short-lived, was it not?” There was no further discussion of the issue.

Failure to Debunk Hall’s Hypothesis

Now let us couple this suppressed evidence of a possible getaway vehicle with two other pieces of evidence that Abedi fled the scene after depositing his rucksack. The first again comes from police radio communications, which, thanks to Hall, you can listen to first-hand by clicking on the time stamp links below:

BTP [British Transport Police] Sergeant 2202 has been approached by a male, and who said it was an Asian male, put down a rucksack and ran out of the area. Can I give you a description? [...] It’s [...] an Asian male [...] described as wearing glasses, black baseball cap, and it was a large, black rucksack, which he said was hidden by the wall. (09:55, my emphasis)

Salman Abedi was the only person present in the City Room matching that description, and according to the member of the public who reported him, he “ran out of the area.”

From the BBC documentary, “The Night of the Bomb,” BTP PC Dale Allcock recounts:

There was a gentleman, family man, he was with his daughters. I asked him, I said what’s happened, and he said erm there’s a guy, I knew there was, I knew, I knew, there was something wrong with him. He said he threw his bag and there was a large explosion and he ran off. I’m thinking right he’s at large. (10:22, my emphasis)

So, there were at least two reports by members of the public of someone (in one case matching Abedi’s description) setting down a rucksack/bag (which in the other case exploded) and running off.

Hall’s hypothesis that Abedi set up a getaway vehicle, returned with a large rucksack containing some kind of device, and waited out of view of CCTV for 38 minutes before depositing that device at the corner of the wall next to the merchandise stall and running away is, thus, perfectly consistent with the available evidence.

It should be straightforward to debunk Hall’s hypothesis by producing the remaining CCTV footage relating to Abedi. For example, why not release the footage from the Trinity Way tunnel? As Hall told Davison, “Now if you will, if you could get the CCTV from the public inquiry, you would, you would see, if indeed it happened, him going along the Trinity Way Tunnel.” That would settle the matter once and for all. The footage exists, and there is no good reason not to release it. The fact that it has been kept secret is highly suspicious.

The Type of Device Used

In Manchester on Trial, Hall claims that the Inquiry “deliberately misled the public” about the type of device used. The Inquiry was categorical that Salman Abedi detonated a TATP shrapnel bomb (see, for instance, §17.1 of Volume 2.2 of the Inquiry report). Like the Sentencing Remarks in the Hashem Abedi trial, the Inquiry focused attention on Salman Abedi sourcing the components necessary to make such a bomb, in keeping with its terms of reference.

TATP creates an entropic explosion which generates blast but no heat. A video by Gerard Harbison, who holds a Chemistry Ph.D. from Harvard, appears to show that a TATP explosion emits neither heat, nor light, nor smoke, only blast. Hall notes that 14 Inquiry witnesses reported heat, a bright flash, and smoke when the blast occurred (24:48-28:50), implying that whatever went off in the City Room was not a TATP bomb.

Hall contrasts the two CCTV images below, which show the same location at 22:04:20 and 22:36:31. Five minutes after the blast, there is evidently smoke in the City Room:

Source: Hall, Manchester on Trial (28:34).

As argued in Part 2, there is evidence that a smoke machine may have been used to simulate the after-effects of a bomb. But this could not have been a TATP bomb.

Redactions

CCTV imagery post-detonation was so heavily redacted that almost nothing remained visible. For example, Hall contrasts two images from same CCTV camera from just before and soon after the blast:

Source: Hall, Manchester on Trial (1:01:50).

The official reason for this is that the scene was one of carnage and the content was too graphic to show to the public [180]. This logic was mirrored during the Inquiry hearings, when all witnesses who were present in the City Room were told explicitly that they would not be asked to describe what they witnessed (so as not to cause distress to anyone) and that images of the City Room would not be shown.

This meant there was a blackout on primary empirical evidence.

Even if one were to accept the official reasoning for the CCTV blackout, however, Hall raises an interesting question, namely, why was the coloured area below, which would not have been affected by the blast, redacted by the Inquiry?

Source: Hall, Manchester on Trial (1:02:25). (The red dots mark the approximate locations of unharmed victims.)

The last unredacted CCTV image of that area was captured at 22:09:50:

Source: Richplanet.net

What took place in this tucked away area during the 21 minutes and ten seconds leading up to detonation? Why was the moving footage for this seemingly innocuous area not made publicly available?

After the blast, all CCTV images of that area have the same large area redacted. Why?

Source: Richplanet.net

The image above is the last available image of the area in question. Who is the GMP officer talking to in the image above, and why have they been redacted? What is in front of the lift that the public must not be allowed to see? There is no evidence that dead bodies or body parts found their way to this location.

Conclusion

Summary of the Argument

The Richard D. Hall case has been one long exercise in using the power of the law to suppress the truth.

The official “reality” of what took place in the City Room on May 22, 2017, rests on the flimsiest of intellectual foundations, namely, the fallacy that Hashem Abedi’s conviction “proves” that Salman Abedi detonated a TATP shrapnel bomb, plus the additional fallacy that a succession of High Court judges agreeing on that proposition makes it true.

As we have seen, Steyn’s false interpretation of the Parker photograph makes it obvious that these High Court judges cannot be trusted to perform the most basic analysis of primary forensic evidence, yet still they arrogate unto themselves the right to decree the truth about what took place in the City Room on May 22, 2017.

Wherever the primary evidence regarding the Manchester Arena incident collides with official “reality,” it gets suppressed. The official version of events was rendered infallible for the purposes of the trial, and Hall was not allowed to present his evidence which challenged it.

Conversely, the claimants were allowed to get away with producing no publicly available evidence to corroborate their claims, such as the 20:03 CCTV image which they claim exists, or any medical proof that their injuries were sustained in the City Room.

The result was an unfair trial in which one side was prevented from presenting publicly verifiable evidence, while the other side was not required to do so.

In his post-ruling statement, Hall told the press:

This court has refused consistently, and repeatedly, to examine any primary evidence from the Manchester Incident, which I put forward in my defence. It has also refused my applications to obtain further evidence, which we know exists and would be easy for a court to obtain. I contend, therefore, that this was not a fair trial.

Based on the evidence presented above, who could disagree?

Similarly, the Inquiry had buried key evidence, such as the Barr footage, the Parker photograph, the Bickerstaff video, key sections of police radio communications, and other evidence described in Hall’s book, which he had sent to the chairman plus four counsel of the Inquiry months before the hearings began. They chose to ignore his evidence.

Autopsy reports, crime scene photographs, and other primary evidence of injuries and fatalities were not shown during the Inquiry. Instead, the public has been expected to take Saunders’ word for it that all this evidence exists in the way he claims it does. This is a lot to ask, however, in view of the Inquiry’s provable omissions and distortions of evidence, as well as the retrospective effort to make evidence submitted to the Inquiry inaccessible to the public.

Hall’s contention that the Inquiry deliberately sought to mislead the public cannot easily be dismissed, given his legitimate concerns surrounding the CCTV imagery, the suppression of key sections of police communications audio, and the fact that the effects of a TATP explosion are inconsistent with the accounts of 14 Inquiry witnesses.

No Place for Truth

In a 64-page Judgment, Steyn refers to the truth only once, to underscore that, had the claimants brought a defamation claim, “any attempt [by Hall] to rely on the defence of truth would inevitably have failed” [193]. Similarly in two items of case law cited at [171], the truth appears powerless as a legal defence:

“In many cases of alleged harassment by publication the truth or falsity of what is said may not be of great consequence […] Truth is not a defence to harassment” (Warby J in Hourani);

“Even if there were evidence that the allegations were true, the conduct of the Defendant could still not even arguably be brought within any of the defences recognised by the PHA” (Tugendhat J in Law Society v Kordowski [2011]).

The only other mentions of the truth in the Judgment are by Hall. We can see from this that the trial was never fundamentally about getting to the truth of anything. On the contrary, it was about using lawfare to shut down the truth.

In that context, Hall’s steadfast defence of the truth, in the face of the Prosecution’s barrage of attempts to make him submit to authority at the High Court of Justice, warrants deep admiration:

Mr Price: You say the Kerslake enquiry did not get to the truth of what happened?

Mr Hall: No.

Mr Price: The Saunders enquiry did not get to the truth of what happened?

Mr Hall: No.

Mr Price: The Abedi trial did not get to the truth of what happened?

Mr Hall: I do not believe so. I, I am not as well informed on the Abedi trial. I have not, that is something I have not studied in depth. But there are very unusual anomalies within that trial.

Mr Price: Master Davidson got it wrong?

Mr Hall: In my opinion, yes.

Mr Price: Her Ladyship got it wrong?

Mr Hall: In that particular instance, yes.

Mr Price: Julian Knowles J got it wrong?

Mr Hall: Yes.

Mr Price: And, and not only have they got, got the wrong end of the stick, but they have completely bought a lie, each of these processes?

Mr Hall: Well, millions of people have completely bought a lie. The majority of the population. Having said that, 28% of the population have not bought the lie, as was discovered by King’s College London in their survey. So […] there is no negative or criticism for someone believing what they have seen in the media and, and basing their opinion on the limited information that they have been given. There is no criticism. The majority of people believe a lie, in my opinion, in regards to this issue.

As I have sought to show, in this Part and others, Hall is correct on all counts. The Kerslake and Saunders Inquiries, and the trials of Abedi and Hall, did not get to the truth of what happened in the City Room on May 22, 2017. On the contrary, upon closer examination, they only raise more questions.

The KCL survey from October 2022, to which Hall alludes, reveals that, based on a sample of 4,500 people,

28% of the public say they think the real truth about the Manchester Arena bombing is being kept from the public, and a similar proportion – 26% – feel the mainstream media and government are involved in a cover-up relating to the attack.

This is in a wider context in which 35% of those surveyed thought they had not been told “the whole truth about UK terror attacks that have happened over the past couple of decades.”

Is the fact that over a third of the population does not believe the mainstream media and government about major terror attacks the reason why the British state went after Hall? Remember, in the same month the KCL survey came out, the BBC vilified Hall as a “disaster troll” in a piece starring Martin Hibbert. A few weeks later, Hibbert began his legal action against Hall. The aim appears to have been to bolster the official narrative around the Manchester Arena incident while sending out a clear message that dissent around this politically sensitive topic will not be tolerated.

If this entire travesty of justice has indeed been about trying to put a lid on mounting public scepticism, however, then it is almost certain to backfire. The sceptical proportion of the public will be higher now than it was in October 2022, precisely because of the publicity the Hall case has generated and the interest it has attracted.

Well done David, that was a very thorough analysis.