The Law vs. the Truth: Getting to the Bottom of the Richard D. Hall Case

Part 7 - Witness Reliability, Anxiety and Distress

Part 7 - Witness Reliability, Anxiety and Distress

Introduction

So far in this series, it has been established that:

Richard D. Hall presented credible forensic evidence calling the official account of the Manchester Arena incident into question;

the Summary Judgment passed by Master Richard Davison unjustly prevented Hall from entering any of that evidence in his defence while being sued for harassment by Martin and Eve Hibbert;

Hall was unjustly found guilty of harassment;

Hall did not commit a grave abuse of media freedom;

the power of the law has been used to suppress evidence and close down critical inquiry into the events of May 22, 2017.

This article returns to the harassment issue explored in Part 4 and addresses one of four main issues for trial agreed by the parties, namely, “Have the claimants suffered from anxiety and/or distress as a result of the defendant’s conduct?” [31(d)]. The first two of those issues were analysed in Part 4 and the last will be discussed in Part 8.

In a long section [214-44], Steyn considers witness statements from Martin Hibbert, Hibbert’s friend Steven Lloyd, Sarah Gillbard, and Daisy Burke (Eve’s Teaching Assistant and Support Worker and formerly her home carer). All four are uncritically regarded as “honest and reliable witnesses” [214, 230]. They all attest to the anxiety and distress suffered by the claimants.

Thus, there are two main issues to be unpacked here: (i) witness reliability, and (ii) the extent of the alarm and distress suffered by the claimants. Self-evidently, there is no reason to accept the claims of unreliable witnesses.

Let us begin, then, by assessing the reliability of Martin Hibbert as a witness, before turning, in the second half of the article, to an assessment of the anxiety and distress allegedly caused by Hall to the claimants.

Was Martin Hibbert an Honest and Reliable Witness?

Hibbert’s False Recollection of the 2018 Video

In his witness statement, which he had time to prepare and verify, and which was presented under oath to the High Court of Justice, Hibbert claimed:

Lee Freeman, who had done the Great Manchester Run that year, was accompanying me to media interviews. On the journey home from an interview with Good Morning Britain in early May 2018 Lee was scrolling through his social media accounts and came across a Youtuber who stated that the arena bomber had never happened as it was a carefully orchestrated exercise carried out by the government to enable them to introduce more stringent restrictions of public rights. He told me the person’s name was Richard D Hall.

[….]

According to the videos, all of the ‘survivors – including Eve and me – and deceased victims had been actors, paid for our services.

Oakley asked Hibbert to verify this information:

Mr Oakley: So, you were fully aware of not only conspiracy theorists but specifically Richard D Hall and his works in May 2018 were you not?

Mr Hibbert: I believe so, yes.

Hibbert added of his exchange with Lee Freeman “I remember it well” and “the one bit I, I remember of it was Richard seemed to have an issue with me talking about the number 22, which I, I found quite funny today bearing in mind what day we started the trial on today.”

However, as the Judgment records, “the 2018 Video does not refer to the claimants by name or show any images of them” [63]. It also came out on June 15, 2018, one month after Hibbert’s exchange with Freeman. So it is not possible that Hibbert heard about a video by Hall matching the description he gave. His recollection was false, his testimony unreliable.

Did Hibbert Have Any Proper Familiarity with the Content of Hall’s Videos?

Hibbert only includes four of Hall’s videos in the conduct complained of [11], yet he evidently did not know that the first of those videos (the 2018 Video) mentions neither him nor Eve.

As for the latter three videos, Defence barrister Paul Oakley was keen to stress in court:

Mr Oakley: [...] Your Ladyship will not need to be reminded, but he who asserts must prove and certainly in respect of the later videos it appeared to me that Mr Hibbert really did not know what was in them, so what is he complaining about?

This is damning. Given that the claimants were suing for harassment, Hibbert should have been able to point out specific evidence of harassment in relation to each element of the conduct complained of [11]. Why was he not able to do so?

The impression of Hibbert’s lack of familiarity with Hall’s work is confirmed by a passage from Hibbert’s 2024 book, Top of the World: Surviving the Manchester Bombing to Scale Kilimanjaro in a Wheelchair, which Oakley read out in court:

A cold hard fury welled inside me. ‘He has done what?’ With trembling hands I did some Googling and discovered that Hall had more than 16 million views and 80,000 subscribers on YouTube.

This, according to Hibbert’s book, was in 2021. But as Davis points out,

What need would Martin Hibbert have of “Googling” Hall in 2021 to discover details about his YouTube channel if this channel was allegedly a source of his “alarm, fear and distress” in 2018? Furthermore, none of Hall’s Manchester Arena work was hosted on YouTube in 2021.

This is yet another reason why Hibbert’s testimony cannot automatically be treated as “honest and reliable” [214].

Why Did Hibbert Keep Changing His Story?

It is not only Hibbert’s statements to the Court that prove unreliable. Ever since going public a month after the Manchester Arena incident, he produced a stream of self-contradictory and demonstrably false claims.

For example, as Hall told the Court (and this was omitted from the Judgment):

Mr Hall: And in particular the [...] Claimants’ statements in particular have been woefully unreliable. Martin Hibbert’s first account of what happened, similar to Josie Howarth, is at complete odds with [...] what has been proven to be true. He said that the bomb went off in the auditorium. […] He said he saw the terrorist going into the auditorium. He said that he was in the auditorium when the bomb went off. It went off in the city room, 50 to 60 metres away. The city room is not an auditorium and it could not be mistaken for an auditorium.

The Manchester Arena auditorium — hardly mistakable for the City Room. Source: ilovemanchester.com

In the summary judgment hearing, Hall told Davison:

Mr Hall: Now, in chapter 2 of my document [...] I analyse many of the inconsistencies made by [...] Martin Hibbert in his interviews. And this is just a very brief summary. It is in detail in […] this evidence, but I just want to summarise it. Martin Hibbert says a terrorist went into the auditorium. This is untrue. He said he brushed shoulders with a terrorist. This is untrue. He said he bumped into the terrorist. This is untrue. He said the bomb went off in the auditorium. This is untrue. He said he saw his daughter being taken away first. This is untrue. He said that his daughter had been covered up with a towel. This is untrue. It has been claimed that he was 2 feet from the blast, 6 metres from the blast, 30 feet from the blast and 10 metres from the blast. At first, he said he was in a coma for 4 to 5 weeks. This then changed to a couple of weeks. He has also claimed that he woke up after a couple of days, although claims not to remember this. The Hibberts do not appear to be in any of the public inquiry released CCTV images nor in the John Barr video nor in the Chris Parker photograph.

All of these claims can be verified with reference to Hall’s evidence document below, and in his video, Table For Two.

For example, in Hibbert’s first public interview about Manchester, with the Sunday Times on July 22, 2017 (available here), he claimed:

We had come out of the box and gone into the main auditorium. But I brushed shoulders with him, the terrorist, and the trajectory of that took me thankfully away from him. He was going in as we were coming out. We got about half-way down the auditorium, going towards the exit and that’s when the bomb went off.

The alleged bomb did not go off in the auditorium, however. It went off in the City Room, which was separated from the auditorium by the concourse. Notwithstanding Hibbert’s alleged injuries, this seems like a major fact to have got wrong.

A headline in the Sunday Times, July 22, 2017

Hibbert, in his Sunday Times interview, claims

there was a lot of blood. At that point I knew I was dying because the blood pool was just so big and I started shaking and going cold.

The Barr footage and the Parker photograph do not show any large pools of blood, and it is a mystery, under those circumstances, why it took over two hours for the claimants to be taken to hospital (see Part 6 and Part 20) and how they were still alive (see the section on injuries below).

In an interview with LADbible on May 22, 2018 (the first anniversary of the Manchester Arena incident), Hibbert claimed:

I bumped into him [Abedi], actually. The police told me afterwards. Apparently as I rushed through some doors, you see us on CCTV coming together. [...] A few moments later the explosion happened.

So, now the location has been corrected from the auditorium to the foyer, and Hibbert is no longer relying on his own faulty memory, but, rather, on what CCTV footage shows, and what the police have told him based on that footage.

Yet, as Hall observed, that claim, too, can be debunked:

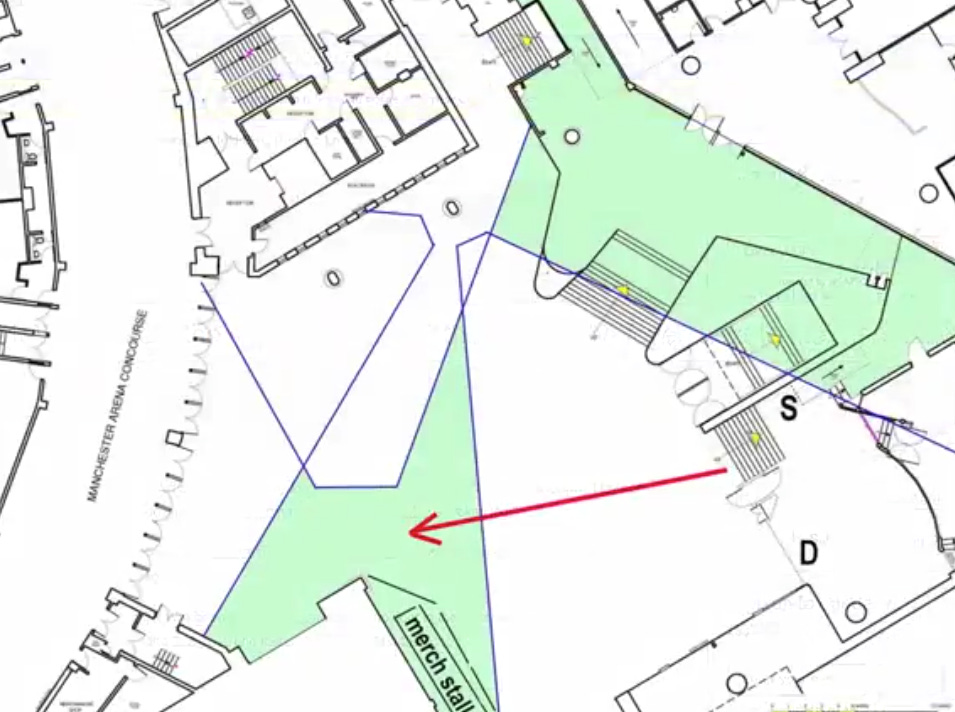

[Hibbert’s] amended claim still seems dubious because Abedi sat near the McDonald’s steps for a long period before walking into the centre of the foyer where he set off his device. He [Abedi] did not go near the City Room doors. Hibbert could not have come together with the terrorist as he went through the City Room doors.

Thus, familiarity with the primary empirical evidence is sufficient to prove Hibbert wrong, again.

Point S marks where Salman Abedi hid at the top of the MacDonald’s steps before moving towards the detonation site as shown by the red arrow. The doors to the concourse are on the left of the picture. Source: Hall, Manchester on Trial.

The LADbible article is obvious propaganda. In it, Hibbert claims “My body was full of golf-ball sized holes. There wasn't a part of me that wasn't bleeding” and “I was there maybe 45 minutes,” Yet, miraculously, he did not bleed out.

PC Jason Hague, of British Transport Police, adds to the misimpression of blood everywhere: “Whenever I think back to that night, my overwhelming memory is of the colour red. Blood was everywhere. In puddles on the floor, all over the walls, drenching the injured. There was literally a red tint in the air.” Yet, here is the Parker photograph, taken approximately four minutes after the alleged blast:

Where are the “puddles of blood,” the blood “all over the walls,” the “drenching” of the injured in blood, or the “red tint in the air”?

Hibbert’s position shifted again with his second witness statement in the application for summary judgment, where he claimed:

At first, I was only using the information I was given by the family liaison officer. It was the family liaison officer that said I’d brushed shoulders with Abedi. Later, the FLO explained they simply meant it as a figure of speech that I had been very close to Abedi.

This is Hibbert rewinding from his 2017 Times interview claim that he had literally “brushed shoulders” with Abedi, but it still does not explain why he reiterated the “bumping into” Abedi claim on May 22, 2018, unless we are to assume that the FLO explained herself after that date (for which no corroborating evidence has been provided).

More serious is Hibbert’s apparent U-turn on the CCTV footage. Hibbert claimed in the LADbible interview that “as I rushed through some doors, you see us on CCTV coming together.” Hall’s unchallenged testimony in the summary judgment hearing, however, was that “they [the claimants] are now saying that that did not happen on CCTV. They are saying there was no contact on CCTV.” If there was no contact on CCTV, then on what basis can the claims made in the LADbible interview be sustained?

Thus, entering the trial, Hibbert rolled back on both his 2017 and 2018 claims regarding his alleged physical contact with Abedi. First the alleged physical contact with Abedi occurred in the auditorium, then it did not but was captured on CCTV near the City Room doors. Then it was reduced from a literal event to a “figure of speech.” Then it was not recorded on CCTV after all. Is there any part of Hibbert’s recollection of events that is reliable?

Unreliable Injury Accounts

In Part 3, we saw that Hibbert’s account of his injuries in LadBible in 2018 did not match the supposed X-ray of him that had been released by the media. His description read as follows:

My feet, legs, arms and jaw were all smashed. One had severed my spinal column. My throat had a part missing. There was one bolt in my face.

In his testimony to the Inquiry in July 2021, Hibbert’s account of his wounds had changed. There were now additional shrapnel wounds to his buttocks and ankles but he did not mention his jaw being smashed or the bolt embedded in his face. In addition to the two most serious wounds (to the spinal cord and neck), Hibbert testified that

All the other 20 shrapnel wounds were all over my back, my buttocks, my legs. My tibia and fibia were shattered, my ankles.

The inconsistency between his 2018 and 2021 descriptions of his injuries offers further reason to question his reliability as a witness.

Martin Hibbert giving evidence to the Inquiry on July 22, 2021.

Despite having suffered 22 close range shrapnel wounds to seemingly every area of his body apart from his internal organs, and despite being able to “see her [Eve’s] brains” while lying critically injured on the floor, Hibbert testified to the Inquiry that “I wasn’t in any pain. I wasn’t panicking” (43:15). Although there is no way of disproving this claim, it does seem counter-intuitive, to say the least. If Hibbert sustained his injuries as a result of standing six metres away from a TATP shrapnel bomb, perhaps his claim is trauma-induced. At any rate, there are obvious reasons why it should not automatically be treated as reliable.

Hibbert told the Inquiry that he had been left paralysed from the belly button down by the blast, with a complete T10 spinal cord injury. However, video footage exists from March 2018 showing him using weights machines with his legs (47:39-48:50), and in a BBC article from November 2019 he claims to be able to stand up and lift up his leg to put a shoe on.

Hibbert told the Inquiry that his second most serious injury involved a bolt that hit him in the side of the neck, severing two main arteries. Yet, even though it only takes 2-5 minutes for arterial bleeding to become fatal, he managed to stay alive for over two hours before arriving at hospital (see Part 6).

More astonishingly still, he told the Inquiry,

for some unknown reason, that bolt didn’t go straight through my neck. I swallowed it, and it ended up in my stomach, which again baffled the experts [given the speed of the bolt and Hibbert’s proximity to the blast epicentre], and nobody can give an explanation of how that has happened, but it did. (44:10)

It is difficult to see how this could be possible. For instance, what stopped the bolt in Hibbert’s neck? Without seeing any primary medical evidence to support this claim, there is no obvious reason to believe it.

No less “baffling” is the fact that, with two severed arteries and 22 shrapnel wounds, and with Eve lying next to him “almost as though she had been shot through the head” (43:15), Hibbert and his daughter managed to survive for almost two hours before being taken to hospital. They only reached the casualty clearing station at 23:25:54 and 23:29:49, respectively, and were only taken to hospital at 00:24 and 00:18, respectively. Thus, Hibbert testified:

It’s just baffling why she wasn’t put into an ambulance straight away. It’s a miracle that she is still with us, given the extent of her injuries [...] Given the amount of blood that I had certainly lost, and given Eve’s injuries, the fact that we are still in the vicinity nearly two hours later… There’s just no words for it. (55:20)

Not only did Eve survive, but she was also “the only person to survive that injury [a bolt through the brain] in the world,” according to her father. Hibbert himself used the language of “Guardian Angel” and “miracle” in tacit recognition of how implausible his account sounded.

Even after two hours, and despite tourniquets being applied, Hibbert told the Inquiry that he was “still bleeding quite heavily” in the ambulance, where he started to vomit blood and was given a blood clotting medication. Is it possible for someone with two severed main arteries plus 21 additional wounds to bleed heavily for two hours, and then vomit blood, without dying?

Paramedics Paul Harvey and Michal Walczak (Inquiry ref INQ020129), according to Hibbert, defied instructions to go to Wythenshawe Hospital, knowing that he would not survive the journey, and instead went to Salford Royal, which was closer (56:20). This adds to the drama, but are we really to believe that after losing large amounts of blood for two hours, all of a sudden the difference between life and death came down to a few additional minutes in an ambulance?

Martin Hibbert’s Claimed Anxiety and Distress

In light of Hibbert’s dubious reliability as a witness, let us turn to his claims that Hall caused him and Eve anxiety and distress.

Was Hall a Threat to the Claimants?

Hibbert testified that, after the police notified Gillbard of Hall’s visit to her home, he worried “What if he [Hall] came to me? What if he tried to harm a member of my family? The ‘what if’ just wouldn’t stop going round and round in my mind” [220].

For context, this was fully 22 months after Hall’s one and only in-person visit to a home that was not Hibbert’s. Hibbert had never met Hall, or exchanged any words with him, and was apparently unaware of the one short, politely worded Facebook message that Hall sent him on August 24, 2019 (see p. 222 of the Book).

Up to that point, Hibbert had not deemed Hall’s conduct to be sufficiently serious to warn his ex-wife about him:

Mr Oakley: So what I am trying to get at is between May of 2018 and the summer of 2021, did Martin raise any concerns with you about the activities of Mr Hall?

Miss Gillbard: When I was notified in the summer ’21, yes.

Mr Oakley: So that was the first time that he raised

Miss Gillbard: Yes.

Mr Oakley: Any concerns with you. [...]

As established in Part 4, there is no evidence that Hall has ever “tried to harm” anyone [220]. Therefore, Hibbert’s concerns were unfounded.

Online Harassment?

Hibbert testified that “Sometimes Mr Hall’s followers would ‘tag’ me in the videos” on social media [222] and complained of five years of relentless online “trolling.” This introduces a new element of perceived threat: not Hall himself, but other people who find his work credible.

“Disaster trolls”: the BBC propaganda term for those who ask evidence-based questions about suspected false flag terrorist events.

Hall is not responsible for the conduct of other people, however. There is no evidence that Hall has ever encouraged anyone to harm anyone else. The words “incite,” “instigate,” and “foment,” for example, do not appear in the Judgment. In all the time that Hall released material on Manchester, none of his “followers” ever tried to harm Hibbert. “Tagging” on social media is not evidence of harm or intent to harm.

Yet, for Hibbert, “It feels as though no one in my life is safe from Mr Hall and his followers” [225]. Even if Hibbert feels this way, there is no reason to regard his feelings as commensurate with objective reality.

No Evidence of Threat to Hibbert’s Physical Safety

Hibbert himself confirmed under cross-examination that there never was any threat to his physical safety or that of his family:

Mr Oakley: “Well all the threats to your physical safety at paragraph 37, those are entirely in your own mind, are they not? There was no objective evidence of any such threat to you or your family, is there?”

Mr Hibbert: “No but I think you have got to the, you know, these videos, the trolling, you know, five years of that. This is not just a one off video that he did in 2018. This is constant, you know, video after video after video, you know, constantly ripping apart my interviews, things that I have said, constant for five years, you know? I think that would bring anybody down, and it does, it changes the way that you think, you know, to the point where I was even scared of going back to my car on my own. I am a 48 year old man and I am scared to go to the car on my own.”

There is only despondency here on Hibbert’s part that the things he has said publicly, over the course of numerous voluntarily given interviews, have been repeatedly challenged, if not discredited (“ripped apart”), by Hall. Hall had every right to challenge those publicly made statements. If Hibbert feels scared to go to his car on his own, that is not because Hall or his “supporters” pose a threat to him; it is because a man in his late forties, who embraces X’s description of him as a “media personality,” cannot handle public criticism.

Steve Lloyd’s Testimony

Hibbert’s friend, Steve Lloyd, under cross-examination, provided no evidence that Hall or his “supporters” represent a “threat” to Hibbert:

Mr Oakley: [...] In respect of those incidents there are no threats of any kind which have been made either by Mr Hall or his supporters, to Mr Hibbert in connection with these concerns that you raise. None at all.

Mr Lloyd: That is correct.

Moreover,

Mr Oakley: [...] Martin’s concern at that time was entirely in his own head, there was no objective evidence of any threat was there?

Mr Lloyd: No, it was, it is, it is the, the feeling. There was no actual –

Thus, even according to Hibbert’s chosen witness, Hall posed no safety threat.

Hibbert and Panorama

In his witness statement, Hibbert claimed that the “huge reaction” to the BBC Panorama programme, which smeared Hall as a “disaster troll” in October 2022, left him feeling “increasingly worried for the safety of myself and Eva [sic].”

Yet, as Oakley argued for the Defence, it is evident from Hibbert’s own words here that his safety concerns arose following his own conscious decision to appear on Panorama, and indeed his subsequent choice to appear on TV to discuss that programme. Hibbert’s choices, Oakley noted, had “nothing do with Mr Hall.”

Martin Hibbert, speaking to BBC Panorama. Source: Daily Mail.

It is worth contrasting the actions of Hibbert and Hall with respect to Panorama:

Mr Oakley: [...] my client [...] was contacted by Panorama 11 times to take part in their programme, and he declined to take part in their programme. You too [...] could have declined to take part in the podcast, Panorama, and in TV shows in the aftermath could you not?

Mr Hibbert: Of course.

Had Hibbert turned down Panorama, he would have drawn far less attention to himself, thereby decreasing the purported risk to his and Eve’s safety that he claims was generated by the “huge reaction” to the programme. Instead, he chose to appear on television repeatedly, and was, therefore, himself responsible for any perceived increase in risk to his and Eve’s safety.

Hibbert complained that his application for summary judgment was met by “approximately 50 of Mr Hall’s followers [who] had travelled to support him in court. I was intimidated.” Perhaps he should not have taken Hall to court in that case, and it is hardly surprising that the public was on Hall’s side, given the spurious nature of the claims being made against him.

Oakley reminded Hibbert of the principle of open justice: “people are perfectly entitled to come into court in most cases and see what is going on, are they not?” Oakley also asked Hibbert “Did you or your legal team complain to Master Davison that you felt intimidated and ask him to clear the court?” To which Hibbert replied “I am not aware.” He himself evidently did not express his intimidation at the time.

Nevertheless, according to Price, “the Court was cleared.” As throughout the legal proceedings, everything just so happened to work in Hibbert’s favour. Davis is correct that “The claimants were supported and protected—favoured—by the High Court at every stage of the litigation.”

The Impact on Eve

Daisy Burke’s Testimony

Steyn finds that

the impact on Eve flows from the defendant’s course of conduct. It is plain that his course of conduct has caused her, as Ms Burke said, “real, lasting and persistent anxiety, and enormous distress” [244].

Omitted from the Judgment, however, is Defence barrister Oakley’s response to Burke’s allegation in cross-examination:

Mr Oakley: If you turn to page 1092. We can see this is the last page of Mr Hall’s letter, and under the heading:

“Remedies”

It says:

“I am not currently, nor do I intend to in the future process your client’s personal data. I am not currently, nor do I intend to in the future pursue any activity that could amount to a harassment of your clients.”

To the best of your knowledge did Eve’s parents tell her that Mr Hall had said quite clearly that he was not going to pursue any activity that could amount to harassment of her?

Miss Burke: I am not sure.

Mr Oakley: So, it is fair to say, is it not, that even though Mr Hall has set out his position very clearly, Eve’s parents have not passed that information on to Eve, have they?

Miss Burke: I am not sure.

[….[

Mr Oakley: Right. I am suggesting to you that if her parents had informed her of what Mr Hall has said in his letter, perhaps not using the exact words, but if they had said something along the lines of Mr Stalker Man is not going to come anywhere near you, there is nothing to worry about, that would have reassured her, would it not?

Miss Burke: Yeah.

Thus, when exposed to new information, i.e., Hall’s proposed remedies in January 2023, Burke conceded that those remedies would have reassured Eve, had she known about them.

The claimants had no idea that Hall had visited Eve’s home in September 2019 until July 2021. It is, therefore, not possible that Eve suffered any anxiety or distress caused by Hall before July 2021.

By Burke’s implicit admission, any anxiety and distress allegedly caused could have been mitigated in January 2023. There was no need for it to be dragged out beyond that point.

Therefore, Steyn is twisting the evidence when using Burke’s testimony to claim that Hall caused Eve “lasting and persistent anxiety, and enormous distress” [244].

Gillbard’s Lack of Awareness of Hall’s Proposed Remedies

Burke was not the only one who was unaware of Hall’s proposed remedies. Incredibly, it emerged at trial that Eve’s mother, Sarah Gillbard, had also not been made aware of them, either by Hibbert, or by Hudgell Solicitors, representing the claimants. When this fact came to light, it drew an audible “wow” from Defence barrister Oakley.

Gillbard was Eve’s “litigation friend,” legally acting on her behalf. It follows that one of the two claimants was unaware of Hall’s pre-action attempt at reconciliation. Any possibility of mitigating Eve’s anxiety and distress was thereby squandered, not by Hall, but, rather, by Hibbert and Hudgell’s. There was never any need for the case to come to court, if serving Eve’s interests really were the primary consideration.

The N161 Form

Omitted from the Judgment is Gillbard’s claim, in her witness statement that “the Defendant sent a letter to our house one day, which caused [Eve] to have flashbacks despite being on these medications.” The aim here was to provide evidence of Hall causing Eve anxiety and distress.

Davis, however, provides some necessary context:

Hall initially appealed the summary judgement barring him from presenting his evidence [...] to the High Court. In order to proceed with the appeal, Hall was required to complete an N161 form and serve notice of the appeal to the claimants. At the time, Hall did not have any legal representation and, when advised by court officials to send copies to the claimants, Hall mistakenly thought this meant he had to send the N161 notification directly to Miss Gillbard and Mr Hibbert. In fact, a reply to the claimants solicitor would have been sufficient.

As Oakley observed, none of this would have happened “had the court case not been initiated,” and Eve, who has the reading age of a nine-year-old, would not have understood it even had she read it. Under cross-examination by Oakley, Gillbard stated that Eve only knew about the letter because she overheard her furiously telling Hibbert about it on the telephone. This implicates Gillbard in Eve’s distress, because Eve did not have to hear about it.

Were Hall or His “Followers” Ever a Threat to Eve?

According to Gillbard’s testimony, Eve “does not like the fact that he [Hall] has been at our home which is meant to be her safe space where no one could get to her and he has made her feel unsafe” [237].

To reiterate: Hall made one visit to Eve’s home, in which he sought to speak with her mother, not Eve, and spoke with neither. He never tried contacting the claimants (or Gillbard) again. He never went near their home again. There is no credible sense in which Hall can be deemed a threat to Eve’s “safe space.”

According to Gillbard, “This is one of the most concerning and unsettling thoughts of all; that one of the Defendant’s followers might start doing what he was doing and investigate and secretly film us” [237]. The logic here is the same as in Hibbert’s testimony above, i.e. appealing to Hall’s “followers” as a perceived source of threat.

In over four years since Hall first mentioned Eve in his Book, there is no evidence that any of Hall’s “followers” has visited Eve’s home or secretly filmed her. Why would they? Certainly Hall has never suggested that anyone should do this. The fear of it happening is unfounded.

“Stalker Man”

After learning of Hall’s one and only visit to her home 22 months earlier, Gillbard encouraged her daughter to be “vigilant” regarding Hall [234], referring to him as “the stalker man” and, like Hibbert, telling Eve about his activities [242]. Gillbard “acknowledged that Eve refers to the defendant as ‘the stalker man’ because that is how she refers to him” [238].

According to Burke’s witness statement, Eve “refers to [Hall] as the stalker man because that is how Sarah [Gillbard] has described him to her. She says things like, ‘he has made a lot of money from the book, and I cannot live my life, it is unfair.’” It is clear that these ideas, which are false (Hall’s income is “only sufficient to enable him to continue his work” [189]), have been planted in Eve’s mind by her mother.

Oakley submitted that any harm to Eve had thereby been caused, not by Hall, but by what her parents had been telling her about him [242].

This was rejected by Steyn on the grounds that

Ms Gillbard first told Eve about the defendant when she learned from the police about his visit. She wanted Eve to be on her guard, and it is unsurprising that Ms Gillbard perceived what he described doing in his video as stalking [...Eve’s] parents [cannot] properly be criticised for explaining to her, in simple terms, what he has done, and what they are seeking to do about it to safeguard her [243].

So, in Steyn's interpretation, “stalker man” is a simple safeguarding term, and not, as Davis contends, “a completely irrational, pejorative interpretation of [Hall’s] behaviour.”

Stalking may have been Gillbard’s perception of Hall’s behaviour, but Hall’s actions do not meet the definition of stalking as defined by Police.uk:

“Stalking and harassment is when someone repeatedly behaves in a way that makes you feel scared, distressed or threatened” (my emphasis).

According the Police.uk definition, stalking may include:

regularly following someone

repeatedly going uninvited to their home

checking someone’s internet use, email or other electronic communication

hanging around somewhere they know the person often visits

interfering with their property

watching or spying on someone

identity theft (signing-up to services, buying things in someone's name)

Hall is guilty of none of these things with respect to Eve or anyone else. As discussed in Part 5, secret recording does not count as spying; it is a routine part of investigative journalism (plus Hall only did it once). A High Court judge must surely know this. Yet, for some reason, Steyn sides with Gillbard in finding it “unsurprising” that Hall should be perceived as a stalker [243].

The kind of image that “stalking” conjures up. It is wholly inappropriate and indeed defamatory to associate Hall with stalking. Source: Protection Against Stalking.

Martin Hibbert wrote in his witness statement: “I worry about her [Eve] worrying about Mr Hall, who she calls the stalker man. She has so much going on she should not have to deal with this as well. It is exhausting having to look over my shoulder all the time.”

Oakley challenged Hibbert on this:

Mr Oakley: Well we looked at the police letter from 5 July 2024 and they do not record any other incidents. You do not mention any other incidents of actual stalking, visiting your respective homes, letters sent in the post by Mr Hall or anything of that kind do you?

Mr Hibbert: No [...].

Thus, police evidence does not support allegations of stalking made against Hall.

There is no reason whatsoever to regard Hall as a “stalker.”

Gillbard and Panorama

The Judgment records that Gillbard “showed the BBC Panorama programme [broadcast on October 31, 2022] to Eve so that she was aware of its contents in case it was mentioned at school” [236]. Oakley described this decision as “very unwise,” given the potential distress it could cause to Eve [242].

Nevertheless, Steyn ruled that there was “no sound basis” for questioning Gillbard’s decision, given that “she knows her daughter better than anyone” (hardly a sound criterion, lest all parental decisions be automatically accepted as valid). The legal force of her ruling, however, is that the Panorama programme was “not adduced in evidence” [243]. Legally speaking, this means that any points relating to it can be disregarded.

Thus, Steyn wants to defend Gillbard showing the Panorama programme to Eve, on the one hand, while ruling out its admissibility as evidence when the Defence raises it, on the other. This is evidence of favouritism.

Interestingly, the “Panorama programme” (a term used nine times in the Judgment) is not referred to as a “documentary” there, other than once in testimony from Burke, even though Panorama is described on its website as an “investigative documentary series.” According to the Cambridge English Dictionary, a “documentary” provides “facts and information about a subject.” So, by not labelling Panorama’s “Disaster Deniers: Hunting the Trolls” episode a “documentary,” the Judgment allows scope for interpreting it as non-fact-based, i.e., as propaganda.

Does Steyn Know What Caused Eve Distress?

Steyn contradicts herself when seeking to specify the cause of Eve’s distress. On the one hand, she finds that

Eve has not learned of his [Hall’s] activities directly, from his publications, but from what she has been told by her parents or overheard, and from the Panorama programme [238].

But, on the other hand,

Eve’s knowledge of what he had done was brought about by his own activities by visiting and then talking about the visit in his publications [243].

So, did Eve learn of Hall’s activities from his publications, or not? Such a contradiction should not be present in a High Court judgment.

Parenting

Not recorded in the Judgment is the contrast drawn by the Defence between the parenting of Eve, who has a reading age of nine, and Hall’s parenting of his son, who had just turned nine. The primary responsibility of parents is to protect their children.

On the one hand, Eve, whose vulnerability is emphasised in the Judgment, has been left anxious and distressed by unfounded stories about the “stalker man” (an appropriate motif for a horror movie), whereas Hall chose not to disclose a single fact about his trial to his son.

As Hall testified,

He does not know I am here. He has never seen any Manchester material. He [...] does not know about my book, and he skips out of school with a big smile on his face. And this, this has affected me, this trial, obviously. But he is completely unaffected [...] by it, because [he] does not know a thing. And I think that is good parenting.

Who could possibly disagree? This is what protecting children really looks like. Children are to be shielded from harm at all costs.

Evidence of Judicial Bias

Evidence of Favouritism Towards the Claimants

We saw in the first half of this article that there is no good reason to treat Hibbert, as Steyn does, as “undoubtedly an honest witness” [62]. Hibbert’s recollections are shifting, self-contradictory, and sometimes demonstrably false. Some of his key claims appear wildly exaggerated and implausible.

Nevertheless, Steyn not only appears willing to accept everything Hibbert says without question, she even makes his case for him when his statements prove false. For example, Steyn gives Hibbert a pass on his false recollection of the 2018 Video:

it seems probable that his recollection of when he first heard of Mr Hall and the content of the first video that he saw is, understandably, in some respects disordered. [62]

Hibbert’s recollection was not “understandably [...] disordered.” It was false. Given that he gave demonstrably false testimony while under oath, Hibbert cannot be described as “undoubtedly an honest witness” [62]. Perhaps he made an honest mistake. Or perhaps he was lying, which would constitute contempt of court. We do not know.

Steyn claims that “It is possible that [...] the video that was drawn to Mr Hibbert’s attention in May 2018” was Hall’s one and only prior video mentioning the Manchester Arena incident [62]. That video is described elsewhere in the Judgment as follows:

On 12 August 2017, Mr Hall published a video in which he said that “in recent months the UK has seen three alleged terrorist attacks”. Mr Hall said:

“I would state that at this point in time, I have no opinion on Westminster or Manchester other than I don’t trust the mainstream media and I wouldn’t trust an inquest. That’s my only opinion at this point in time because I haven’t done a personal investigation.” [47]

The 2017 video was an interview with Dr Nick Kollerstrom about his new book on European false flag terrorism. It was not Hall putting forward his own views, and as the Judgment records, Hall had no opinion on Manchester at that time, having not yet begun his investigation [47].

This is incompatible with Hibbert’s description of Freeman telling him about a video by Hall claiming that “the arena bomber had never happened as it was a carefully orchestrated exercise carried out by the government to enable them to introduce more stringent restrictions of public rights.”

Therefore, Steyn’s suggestion that the 2017 video was the one drawn to Hibbert’s attention in May 2018 cannot be true and shows favouritism towards the claimant.

Steyn continues:

I accept Mr Hibbert’s evidence that it was in 2018 that he first heard of Mr Hall and saw one of his videos, but the content of the video he recalls seeing in December 2018 more closely matches those which were published in 2020, and it is probable that he has misremembered the content of the first video he saw, confusing it with content that he saw later. [64]

There is no good reason to accept Hibbert’s claim that he first saw one of Hall’s videos in 2018. Therefore, why give Hibbert the benefit of the doubt, especially given that he had 20 months to prepare his witness statement accurately and incurred £260,000 of legal costs, mostly in barrister fees, which should have ensured that his evidence was completely accurate?

Consider also Steyn’s reasoning to sustain her finding that Hall caused Eve anxiety and distress:

She accepts Burke’s testimony that Hall caused Eve “real, lasting and persistent anxiety, and enormous distress” [244], without mentioning Burke’s implicit admission that this could have been mitigated in January 2023.

She tacitly sides [188] with Gillbard’s description [238] of Hall as a “stalker,” even though, as a High Court judge, she must have known that Hall’s behaviour in no way met the criteria for stalking.

She defends Gillbard showing the Panorama programme to Eve, while ruling out its admissibility as evidence in relation to the Defence raising it [243].

In each instance, Steyn is not applying the law impartially. Rather, she is consistently skewing her findings in favour of the claimants.

Dame Karen Margaret Steyn KC. Source: Daily Mail

Evidence of Bias Against the Defendant

While Steyn bends over backwards to accommodate the claimants, even making their arguments for them where necessary, she does the opposite in relation to the defendant.

For example, she appears to misrepresent the Defence’s position in the following paragraph of the Judgment:

Mr Oakley submits that Mr Hibbert “has come to the ‘harassment’ and not the converse” by reason of having actively sought to uncover the existence of Mr Hall’s publications, and by making a positive choice to engage with the mainstream media to the extent that he is described as a “media personality” by X on his X profile. [195]

Yet, unless this was in a written submission by Oakley, there is no record in the trial transcript of him using the phrase quoted.

Nor is there any evidence in the trial transcript of Oakley arguing that Hibbert actively sought to uncover the existence of Hall’s publications. For example, a search of the trial transcript for the terms “seek,” “sought,” and “publications” does not reveal that information.

The only “active choice” that Oakley highlighted in relation to Hibbert was the latter’s decision to take legal action against Hall in October 2022, having claimed in May 2018 that words would never hurt him and that he was happy to let sleeping dogs lie.

Oakley established from Hibbert that he was happy for X to describe him as a “media personality” on his profile, but said nothing in this context about “coming to the ‘harassment.’”

The second half of paragraph 195 reads as follows:

He [Oakley] also contended that it was “very unwise” of Ms Gillbard to allow Eve to watch the Panorama programme, which related the narrative that Mr Hall was putting forward in his publications. As I understand it, the legal submission underlying both contentions is that the course of conduct was not harassment because it was not targeted at the claimants. [195]

This is a straw man. In fact, Oakley was arguing that Hibbert, as a “media personality,” cannot “control how people talk about him” and that the source of Eve’s alarm and distress was not Hall but, rather, her own parents.

As Davis notes, the role of a judge in a bench trial (not involving a jury) is to “ensure proper procedures are followed and oversee a fair trial before making a judgment on the basis of the evidence presented and legal arguments made at trial.” It is not to make the case for one side or the other; that is the role of the respective barristers. Based on the evidence above, though, Davis is correct that Steyn “appears to have overstepped the remit of a bench judge.”

Conclusion

One of the main issues for trial agreed by the parties was “Have the claimants suffered from anxiety and/or distress as a result of the defendant’s conduct?” [31(d)]. All four witness statements given on behalf of the Prosecution attest to the anxiety and distress suffered by the claimants, and all four witnesses are treated by Steyn as “honest and reliable” [214, 230]. Hibbert receives the special distinction of being “undoubtedly an honest witness” [62].

As demonstrated above, however, there are numerous reasons — from shifting, false, and self-contradictory recollections of Hall’s work and of what took place in the Arena, to unlikely claims of privileged access to CCTV footage, to inconsistent and occasionally improbable accounts of his injuries — why Hibbert should not automatically be regarded as an honest and reliable witness. If anything, he seems consistently unreliable.

Therefore, Hibbert’s account of the anxiety and distress allegedly caused by Hall to him and Eve must be treated with scepticism. For example, despite his paranoia that Hall might try to harm him or a member of his family [220], there is no evidence that Hall or his “followers” ever posed a threat, either online or physically.

Far from Hall causing Eve “real, lasting and persistent anxiety, and enormous distress” [244], to quote Burke, Eve did not know anything about Hall until July 2021 and would not have known anything about Hall had her parents not told her about him.

As soon as Hall learned of the claimants’ alleged distress, he proposed a remedy that should have provided the necessary reassurances, but neither Hudgell Solicitors nor Hibbert thought it worth making Eve and her mother aware of that proposed remedy.

Instead, both of Eve’s parents made their daughter unnecessarily anxious and distressed by repeatedly referring to Hall as “the Stalker man.” Hibbert volunteered to appear on Panorama and in the media, and Gillbard then showed the Panorama programme to Eve. None of this was Hall’s fault.

Although these are the objective facts of the case, Steyn, in her Judgment, bends over backwards to skew those facts in favour of the claimants, while misrepresenting and straw manning the Defence’s position.

It is, therefore, beyond reasonable doubt that Hall’s conviction represents a miscarriage of justice.

Thank you for this superb detailed series analysing the case of Hibbert vs Richard Hall. This has helped me greatly to understand the important forensic investigation work of Hall and the disgusting way in which he has been treated by the U.K. state apparatus in an attempt to cover up their crimes against the people. It is so important that this is getting attention when the rest of the alternative media has largely ignored the implications of this verdict.

While I have always believed MI5-6 orchestrated this event, I don't accept the idea that a giant bomb in a major English city in a huge concert venue didn't happen. Yes, I'm sure he was stitched up at the trial also. It was a false flag and this is an easy way to convince the world it wasn't.