Part 20 - The Casualty Clearing Station

Introduction

After five months of hard work, I am relieved to announce that this is the final Part of the series.

Part 19 explored the theme of medical treatment, arguing that there is very little hard evidence of seriously injured people being treated.

This Part focuses on one very important element of the care said to have been provided to casualties, namely, the Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), which is where 38 of the most seriously injured individuals were officially taken before they left for hospital in ambulances.

I begin by showing where the CCS was located and what it looked like. Essentially, it was just an area of the train station concourse next to the War Memorial entrance to Station Approach, the road where ambulances arrived.

North West Ambulance Service’s triaging system is then explained, from P1 (the most urgent type of casualty) to P3 (the “walking wounded”). It is not clear that it worked effectively on the night.

What medical treatment was provided at the CCS? Here, surely, there should be extensive evidence of paramedics treating casualties, yet, once again, this proves not to be the case.

For some reason, the Inquiry report does not provide a list of the 38 casualties who were taken to the CCS. Yet, at least 25 of the 38 casualties can be identified from Inquiry documentation alone, and a further two are easy to identify by cross-referencing that documentation against legacy media reports.

I name the 27 whom the Inquiry helps us to place at the CCS, list others who could theoretically have been present, and rule out “survivors” who definitely were not.

Although it is possible that 38 alleged casualties is too high a figure, 38 seems reasonable based on the evidence.

Based on official sources, questions arise concerning what happened to Freya Lewis and Ruth Murrell at the CCS. As Pighooey has demonstrated, they disappear from CCTV long before their official departure times to hospital. Where did they go?

The plot thickens regarding Ruth Murrell. In Part 18, I questioned whether she was the woman at the bottom of the steps in the City Room, and Iain Davis has since published a welcome and thoughtful response on the matter. I advance the conversation further below.

As observed by Pighooey, Lewis and Murrell are not the only casualties in the War Memorial entrance who disappear ahead of time. Four of those seven casualties mysteriously vanish when they should still be present.

I draw attention to a hitherto unexamined source of evidence, namely, ambulance loading officer Matthew Calderbank’s notes. They give the total number of casualties taken to hospital as 59 (the same figure given by Prime Minister Theresa May in her announcement on May 23, 2017), and they break down the casualties according to P1, P2, and P3 status. But they also note that 14 casualties were taken to hospital by bus, something for which there appears to be very little corroborating evidence.

Why were casualties who allegedly were critically injured not taken to hospital sooner? Instead of taking those casualties straight to hospital, many were officially left to lie on the cold floor of the station concourse for hours and could have died from their injuries. There was easily enough capacity within the Greater Manchester hospital network to deal with a mass casualty event, and enough ambulances were available by 23:15.

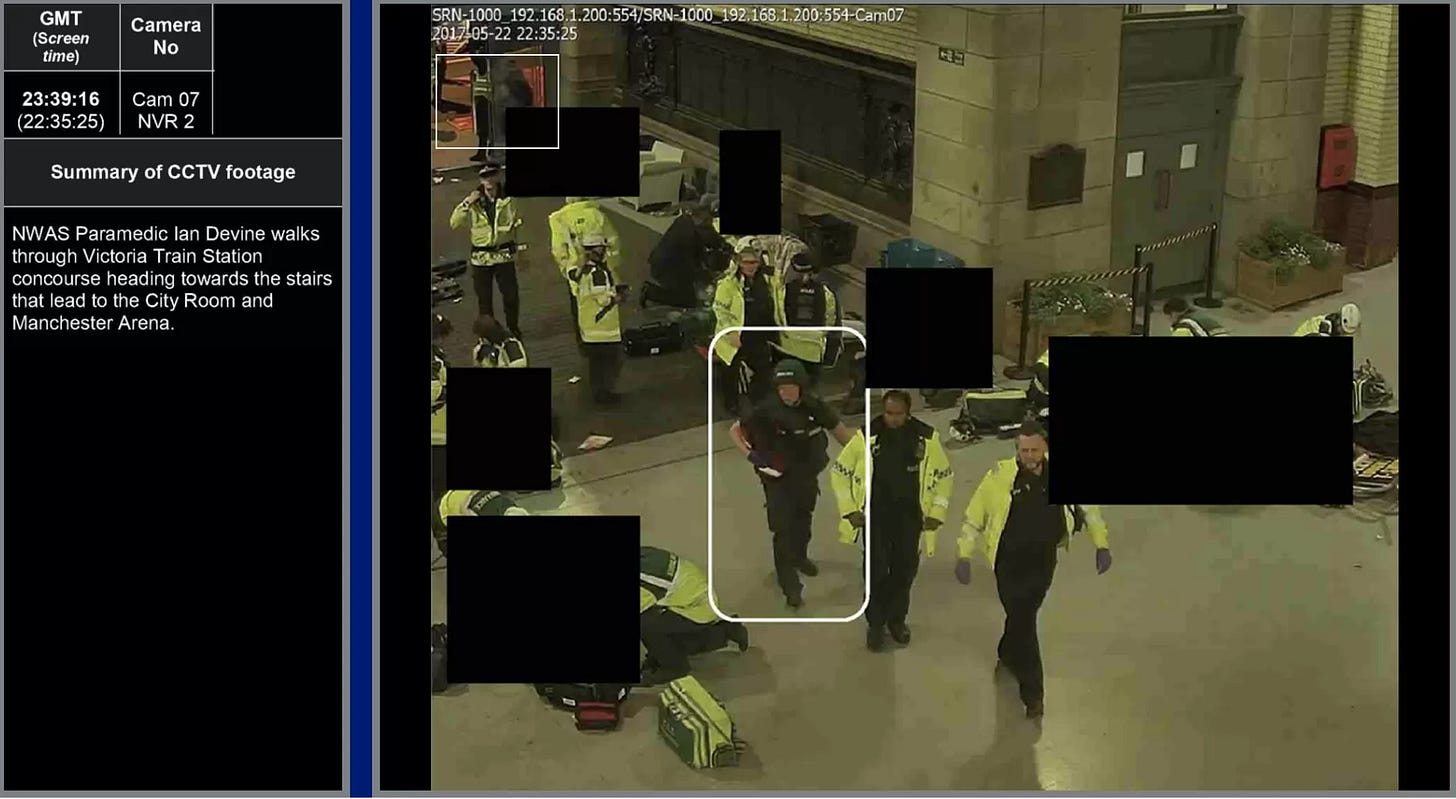

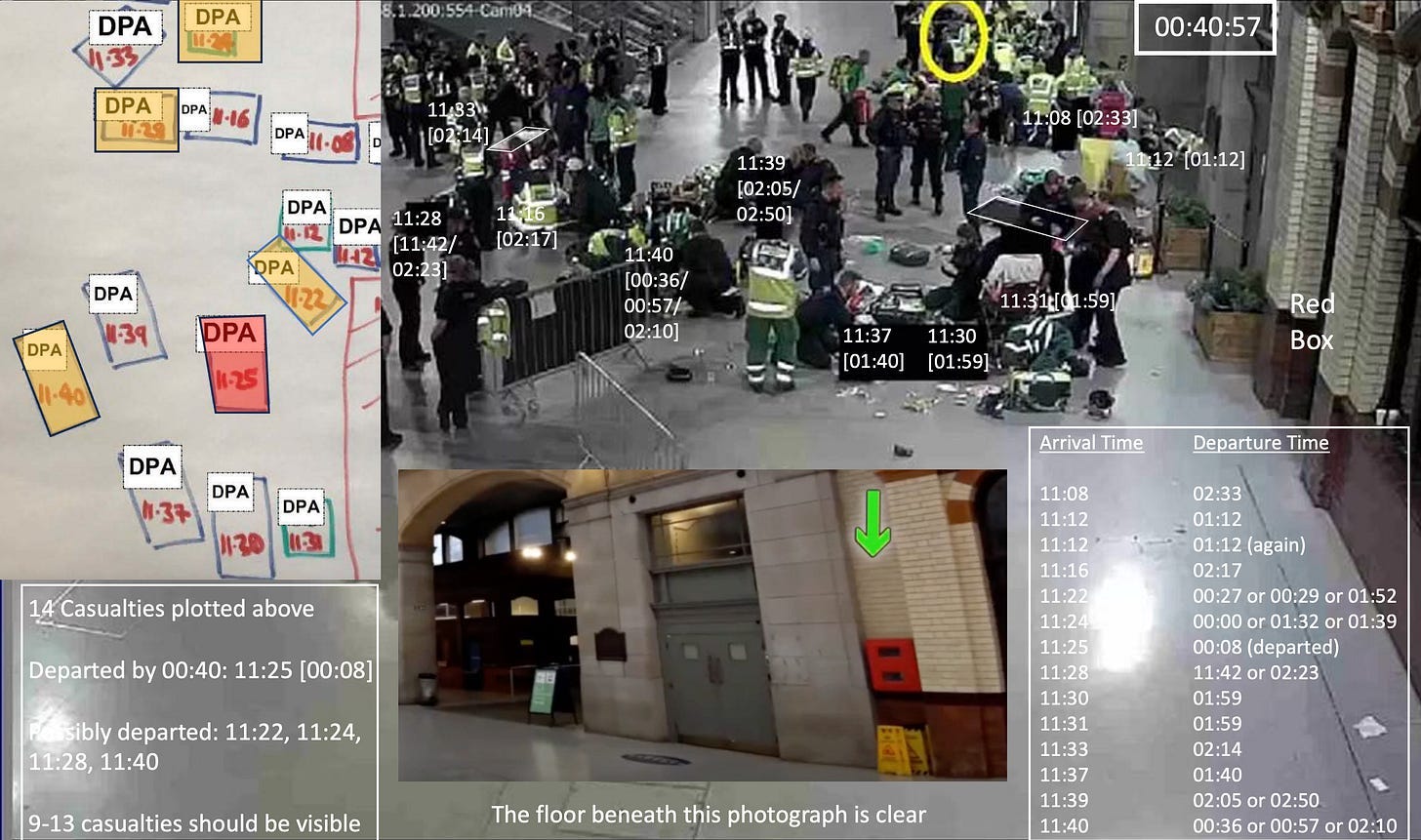

Finally, I offer some observations on the 00:40:57 CCTV Image of the CCS, because no one so far has paid close attention to this particular CCTV camera view of the area. A few minor novel insights emerge.

Locating the Casualty Clearing Station

A Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) is an area in which casualties receive treatment before being moved to hospital in a mass casualty situation (§10.169). NWAS Bronze Commander Daniel Smith decided to set up the CCS by the War Memorial entrance to Manchester Victoria train station (§10.169).

The location of the CCS — next to Station Approach (the road alongside the old station building) where ambulances could pull in, but away from City Room — meant that casualties had to be taken across the footbridge in Victoria station, down two flights of steps at the end of the footbridge, and across the station concourse.

Source: New York Times

The photograph below shows the bottom of the steps from the footbridge.

Source: Pighooey (14:59)

The bottom of the steps can also be seen bottom left in the image below, with the lift to the footbridge visible behind it and the station concourse visible in the foreground.

Source: Pighooey (16:08), with my annotation in white

I have circled the War Memorial, which proves to be a prominent marker, and highlighted the exit to Victoria Station Approach with a white rectangle.

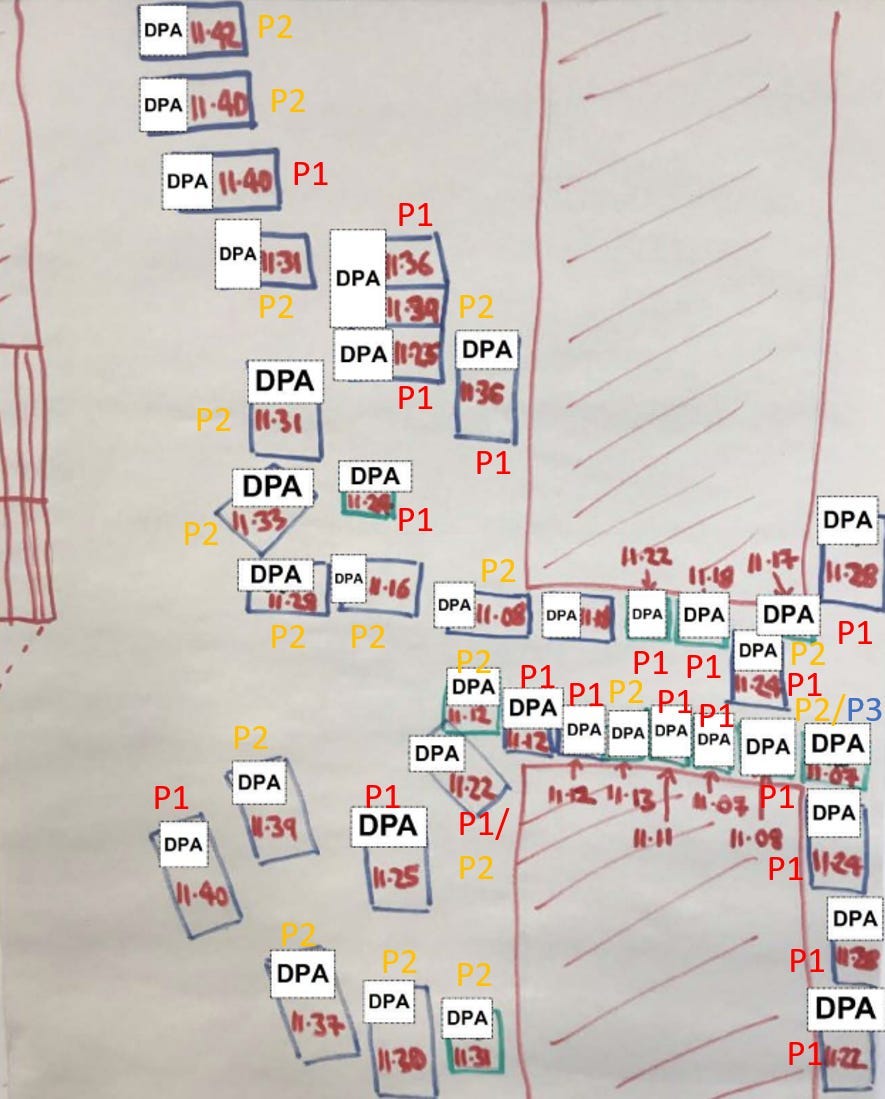

The same exit is marked as “War Memorial Entrance” in the hand-sketched diagram below, whose provenance is uncertain, but which, according to the Inquiry, shows where the 38 casualties who were taken to the CCS were located and what time they arrived.

Source: Volume 2.1 of the Inquiry Report, Figure 38 (§14.428) [INQ041266]

To give an idea of what the CCS looked like in action, below is a CCTV image captured at 00:54:39.

Source:Richplanet.net

Triaging

North West Ambulance Service’s (NWAS) triaging system had three priority levels: P1, P2, and P3:

P1 casualties require immediate life-saving interventions. P2 casualties require surgical or other interventions within two to four hours. Treatment for P3 casualties [a.k.a. the walking wounded] can safely be delayed beyond four hours. (§12.404)

There was also a P4 category (“Expectant”), which relates to anyone expected to die, and was not used on the night (§12.404). This appears to be because NWAS’ Major Incident Response Plan states that only the Forward Doctor may categorise people as P4, yet Daniel Smith failed to appoint a Forward Doctor (§14.233). Still, it seems odd that no one was classified as expected to die, given that 22 people were declared dead over a period of approximately one and a half hours.

HART paramedics Nick Priest and Simon Beswick co-ordinated the arrival of patients at the CCS:

We had a section with P1 patients indicated with red sheeting, and yellow sheeting for P2’s — P3’s were sent across the road and were dealt with by others members of staff. (p. 5)

If this is true, then the only CCTV evidence of it indicates that some red sheeting may have been placed outside. There is no evidence of red and yellow sheeting inside.

Source: Richplanet.net, with my annotation in white in the top left

38 P1 and P2 casualties were taken to the Casualty Clearing Station (§10.170). It is evident from the spreadsheet of arrivals at the CCS (which is not included in the Inquiry report) that P1 casualties were not prioritised ahead of P2 casualties:

Source: National Archives

At the end of the “golden hour” (the critical first hour of emergency response time), i.e., by 23:31, there were still four P1 casualties in the City Room (§10.219).

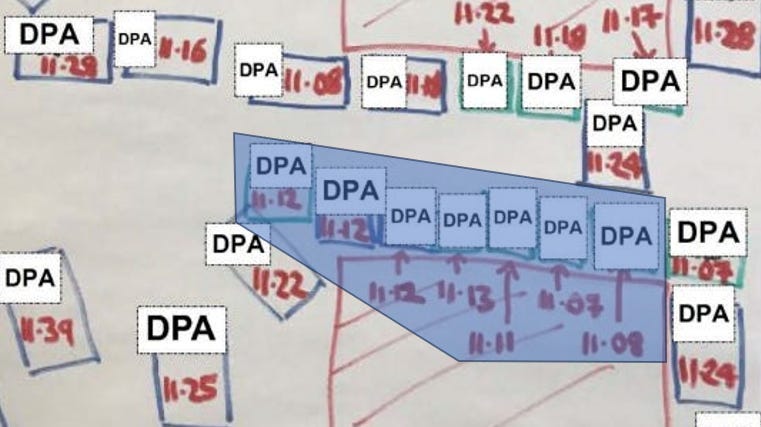

The P1 vs. P2 distinction can be broadly seen in my annotated version of the CCS map below, which is based on information from the spreadsheet. As is to be expected, most P1 patients are located near the exit, or centrally, with a few late-arriving exceptions, while most P2 are spread along the station concourse.

Source: National Archives, with my annotations of P1 and P2 status

For some reason, ten of the 38 boxes in the above diagram are drawn in green, whereas the other 28 are drawn in blue. The Inquiry report does not explain why this is, but it appears to be deliberate. For example, at 11:12, there is one green box and two blue boxes next to each other. Why change pen inside the same minute?

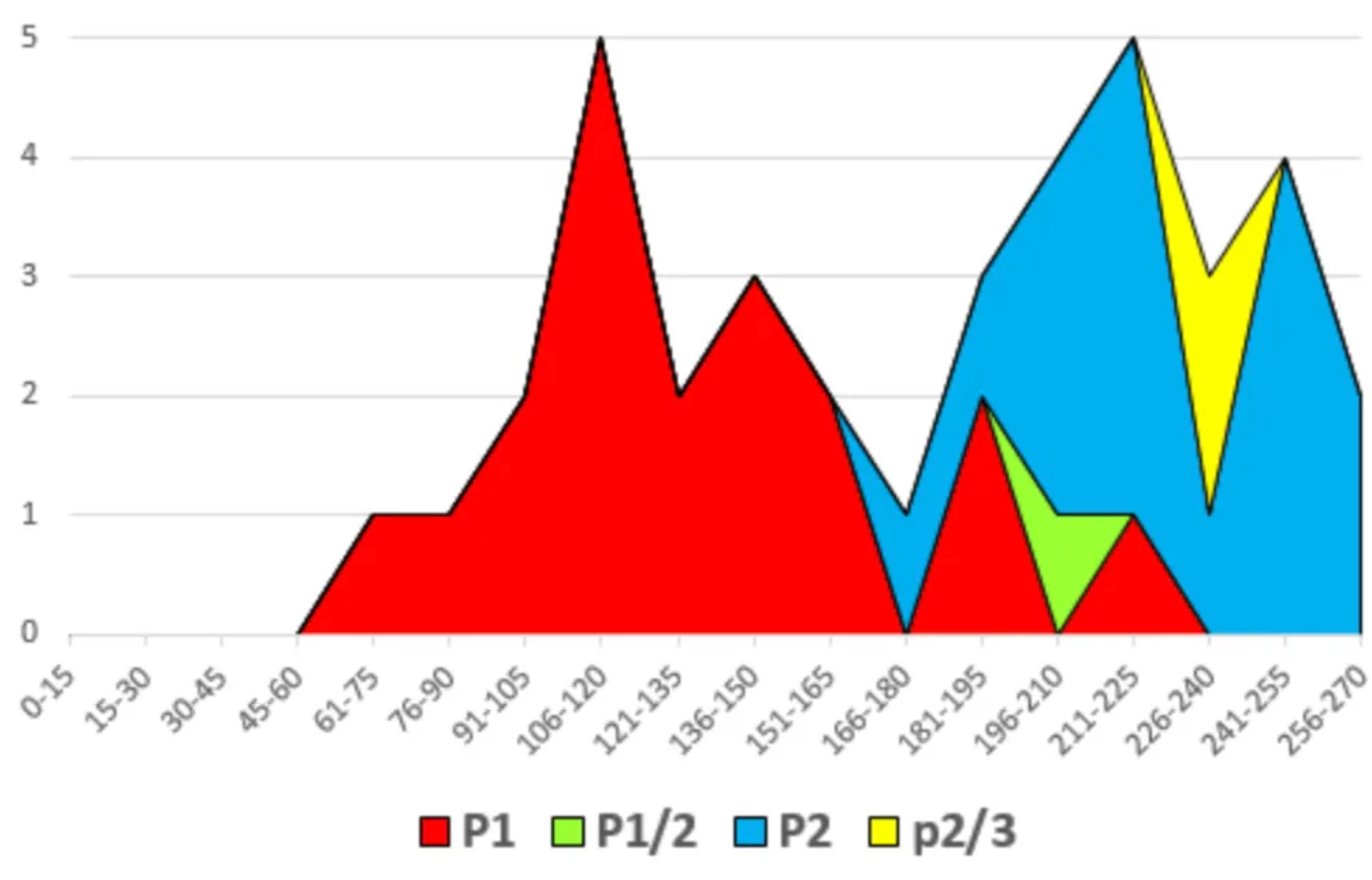

P1 casualties were generally taken to hospital before P2 casualties, as one would expect. The graph below shows how many minutes casualties had to wait (by priority status) from the moment of detonation to their departure time for hospital.

y-axis = number of casualties; x-axis = number of minutes from official detonation time to departure from hospital. Graph submitted by a subscriber

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that Casualty No. 34 on the CCS spreadsheet (a P2) had apparently deteriorated to P1 status by the time he/she was put into an ambulance (see Loading Officer Matthew Calderbank’s notes), yet was the last to leave for hospital at 02:50 am, i.e., four hours and 20 minutes post-detonation. We seem to be dealing here with yet another miracle survivor.

What Treatment Was Given at the Casualty Clearing Station?

It is remarkably hard to find evidence of treatment being given to patients at the CCS.

For example, NWAS’ Daniel Smith told the Inquiry that, in his capacity as Bronze Commander,

Part of my job at scene is not necessarily — and I totally appreciate that this will seem strange to people — is not necessarily to direct immediate care and treatment, but to start setting up the system to enable us to manage all treatment […] (48:58).

Hall notes that the following paramedics, in their statements to the Inquiry, either “did not treat anyone or their role was not to treat anyone”: Patrick Ennis, Christopher Hargreaves, Daniel Smith, Joanne Hedges, and Helen Mottram, plus NWAS associate medical director Edward Tun (§4.10.3), who self-deployed with his son Joe, a HART paramedic.

Hedges and Mottram went round triaging patients in the CCS (as P1, P2, or P3). Hedges assigned ambulance crews to treat them and brought the crews bandages and equipment (pp. 50, 56). However, when Saunders asked Hedges “But you wouldn’t personally be doing the treatment?,” she replied “No” (p. 93). And when Saunders asked Mottram “So did you actually treat any of these casualties?,” she replied “No, I did not” (p. 67; 45:30).

Hedges stated “I don’t recall any issues being brought to my attention of pain relief being required, apart from when an advanced paramedic had turned up to speak to me regarding ketamine” (p. 78; 47:00). Student paramedic Simon Butler claims to have administered ketamine to one patient (p. 134). Were the other 37 victims of a TATP shrapnel bomb not in pain?

Sophie Cartwright QC told Tun “You did not need to provide any hands-on medical assistance to any casualty,” and he replied that this was “very much by design” in his triaging role (45:37).

Simon Beswick claimed in his witness statement:

Once the CCS was established and patients were being brought downstairs to be treated further, my role remained fairly hands off to ensure that I was able to supervise my team and others with direct interventions within the CCS, alongside other senior members of staff present. The CCS quickly filled up with numerous NWAS staff members, ranging from Paramedics to MERIT/ BASICS Doctors. I was reassured by the amount of senior clinicians on scene that casualties would be receiving sufficient care and attention. The only hands on care I recall providing during this time, was performing chest compressions on a female patient whilst the team caring for her were moving her from the CCS to an ambulance vehicle.

So, in period of approximately three hours, Beswick performed chest compressions on one patient. One is reminded of Butler’s claim not to have seen a patient actually actively bleeding at the CCS in over three hours (pp. 122-123; 44:50).

HART paramedic Lisa Munro claimed in her witness statement to have inserted a cannula and administered TXA to a girl, before being sent to re-triage P3 casualties, who were across the street.

What about all the other paramedics who treated casualties? Were none of them called to give evidence at the Inquiry? Apart those who dealt with Atkinson, Callander, and Roussos (see Part 19), I cannot find any additional evidence of paramedics telling the Inquiry that they treated anyone. Perhaps I have missed someone: after all, hundreds of witnesses gave evidence, but the £31.6 million Inquiry did not produce an index of witnesses, making it hard to perform a comprehensive check.

All in all, it is easier to find evidence of medical personnel not treating patients at the CCS than it is of them treating patients. Obviously, it should be the other way around.

Hiding The Identities of Those Taken to the Casualty Clearing Station

As well as failing to produce an index of witnesses, the £31.6 million Inquiry failed to specify who was taken to the CCS. A simple list of 38 names would have sufficed.

In places, the Inquiry report seems willing to identify those who died but not those who were taken to the CCS. For example, Showsec’s Megan Balmer

checked on Wendy Fawell, but found there was nothing she could do to help. She sought to provide assistance to Kelly Brewster. She also helped a casualty down to the Casualty Clearing Station. (§16.141)

In another example, John Clarkson and Paul Worsley transported “a young and seriously injured casualty” to the CCS and “stayed with her until an ambulance arrived” (§16.129). It would have been easy enough to name the casualty from legacy media reports, i.e., Lucy Jarvis.

CCTV imagery released by the Inquiry is similarly cautious to maintain the anonymity of those taken to the CCS:

Two unidentified casualties are accompanied down the steps. Source: Richplanet.net

The CCS map and spreadsheet of arrivals redact the names of all casualties. Sophie Cartwright QC noted this at the Inquiry but made no attempt to explain why, nor did Saunders seek an explanation (p. 71). “DPA” on the spreadsheet refers to the Data Protection Act, so presumably the idea is that private medical information (i.e., attendance at the CCS) must not be disclosed.

Yet, as shown in the next section, the identities of 12 (inferentially 14) casualties taken to the CCS are given in different places of the Inquiry report, and the identities of at least a further 13 casualties are evident from the Inquiry transcripts and evidence documents. In that context, the Inquiry itself seems guilty of any potential DPA breaches, and its failure to publish a simple list of who was taken to the CCS (and when) seems like yet more deliberate obfuscation (cf. Part 6 and also Pighooey).

What is the point of such obfuscation? One possibility is that it has to do with provable falsification of evidence at a later date.

In terms of the hard evidence shown to the public, virtually all of it appears to be true (with the exception of the fabricated building damage discussed in Part 12). For example, there is a close correspondence between the evidence summaries provided by Operation Manteline and the CCTV imagery (which does not appear to have been modified).

The problems with the official account come mostly through missing evidence: the lack of primary empirical evidence supporting the explosion of a TATP shrapnel bomb, the redacted areas on CCTV imagery, the omission of Inspector Smith’s claim to have discovered Salman Abedi’s body through the doors to the Arena concourse, failure to play the police radio communications relating to the grey Audi, the lack of hard evidence placing most “survivors” at the scene, etc.

Where demonstrably false information arises in the context of the Inquiry, it tends to be found in dubious witness testimonies, rather than the hard evidence provided to the public.

If the Inquiry had provided all the names of those taken to the CCS, and it were later proven that one or more of those individuals was somewhere else at the time, this would be proof of a cover up and falsification of evidence. The fact that avoiding that risk seems to be the most likely reason for not naming the 38 is very suspicious.

Who Was Taken To The Casualty Clearing Station?

We can work out who most of the 38 casualties taken to the CCS were, based purely on information contained in the Inquiry report and the Inquiry transcripts, with some additional detail to be found in legacy media reports.

The Inquiry Report

The CCS is mentioned 192 times in the 716 pages of Volume 2.1 of the Inquiry report, yet the only names mentioned of those treated at the CCS are two eventual fatalities, Georgina Callander and John Atkinson (§14.444-14.449).

Callander was carried out of the City Room on a makeshift stretcher at 23:27:13 (p. 28), and departed Victoria Station in ambulance number 347 at 23:42:34; she was the first casualty to depart by ambulance (§14.445).

Atkinson was evacuated from the City Room at 23:17, and entered the CCS on a makeshift stretcher at 23:24:55 (§14.446).

Volume 2.1 makes additional mention of “an injured girl and, later, a second injured girl” helped to the CCS by Philip and Kim Dick (§16.171). According to legacy media reports, those girls were Freya Lewis and Aliya Rule; a photograph of Lewis at the CCS was published by the Irish Sun,

Volume 2.2 names Lucy Jarvis (§17.28; cf. p. 64), Janet Senior and Josephine Howarth (§17.50), Martin and Eve Hibbert (§17.58), Paul Price (§17.70), Claire and Hollie Booth (§17.84), Bradley Hurley (§17.102, cf. p. 113), and Lisa Roussos (§17.108) as having attended the CCS.

The CCS is not mentioned in Volumes 1 and 3 of the Inquiry report.

By my reckoning, therefore, the Inquiry report identifies 14 casualties in total being taken to the CCS, 12 of whom are named, and we know who the other two are.

The Inquiry Transcripts

From the Inquiry transcripts we additionally find that:

Eilidh MacLeod’s unnamed friend, who we know to be Laura MacIntyre, was “evacuated from the City Room at 23.36.43” (pp. 65-66);

Robby Potter was carried out on a makeshift stretcher, supposedly down the stairs to the CCS (p. 11), although he appears to have only made it as far as the footbridge, according to Sophie Cartwright QC (p. 61); he was initially treated at Wythenshawe Hospital;

Potter’s partner, Leonora Ogerio, was “transferred down to the station” (p. 22);

Joanne McSorley claimed “I was put on a makeshift stretcher, a board, and I was taken to Victoria Station” (p. 25);

Gary Blamire was triaged as P2, but appears to have been forgotten about as teams moved on to P3, meaning that he had to shout for their attention despite his injuries (p. 74); he was taken to Manchester Royal Infirmary;

Emily Murrell was miscategorised as P2 when she should have been P1, and she “lay in Victoria Station until after 2 am in the morning” (p. 74);

Joanne Haslam’s witness statement places Ruth Murrell with Emily at the CCS (p. 4), and Ruth can also clearly be seen at the CCS in a photograph published in the Irish Sun (cf. Part 16);

Linda Carter was one of the last to be evacuated from the CCS, at or around 02:00 (pp. 74-75);

Lewis Brunton put in his witness statement that two armed police officers “picked me up with my arms round their necks and they helped me down the stairs from the foyer […] I was put on the floor near to an exit and I was handed a card with a number on” (p. 47);

Millie Robson “was taken to a casualty station” and triaged as P2, according to her father, David Robson; and

Pauline Healy (Sorrell Leczkowski’s grandmother) was carried out of the City Room at 23:38:47 (p. 77), presumably making her the penultimate evacuee before Bradley Hurley.

This takes the total number of nameable casualties at the CCS to 25. We are still 13 short of 38, however.

Other Possible Candidates

Revisiting the list of 40 named “survivors” in Part 17, it is possible that some of them were taken to the CCS, although I have no evidence that they were. They are:

Adam Lawler, who “walked across the City Room” with Olivia Campbell-Hardy at 22:30:51 (p. 17), and was reportedly taken to Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital (16:26);

Evie Mills and Amy Barlow, who both met the Queen at Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, having allegedly sustained serious injuries (see Part 17);

Samantha Leczkowski (Sorrell’s mother), who reportedly told the Hashem Abedi trial “I don’t care that my leg doesn’t work”;

Caroline Davies, who was reportedly “injured in the blast”;

Thomas McCallum claimed to have been “significantly injured” and was assisted out of the City Room in a wheelchair (pp. 9-10). Assuming I have identified him correctly, he can be seen on CCTV being wheeled to the War Memorial entrance at 23:00:20. However, his arrival there was seven minutes earlier than anything recorded on the CCS spreadsheet.

According to a GMP summary of CCTV footage, a female evacuee left the City Room on a makeshift stretcher at 23:02:37, with her husband walking alongside. She may have been the first casualty to arrive at the CCS, but I cannot identify her.

Student paramedic Leigh-Sa Smith referred to “a young female who was lying on a makeshift stretcher which I think was some sort of advertising boarding.” She was “to the left of the steps that go up towards the Arena foyer” and “with her dad” (p. 4). Other than Eve Hibbert, I cannot think of any girl who was present in the CCS with her father, but the positioning next to the steps rules out the Hibberts.

Candidates Who Can Be Ruled Out

There are some casualties who we know did not attend the CCS:

Saffie-Rose Roussos was taken to hospital in an ambulance from Trinity Way (p. 33);

Lily Harrison (p. 73) was transported directly to Manchester Royal Infirmary Children’s Hospital in a British Transport Police van, along with Lauren Thorpe and Adam Harrison (p. 22);

Julie Whitley was driven directly to hospital by Christopher Wild (p. 51);

Lisa Bridget exited via New Bridge Street (Trinity Way) and was put in a police vehicle on Great Ducie Street, before being transferred to an ambulance for onward travel to Manchester Royal Infirmary.

The Burke family went across the street to the P3 area (Q. “Was there any stopping in the station area before Catherine was taken across to the Chetham’s School of Music area? A. No” [p. 69]).

Yvonne Clayton was taken to hospital by a policeman (p. 57).

Susan Smith was “taken elsewhere until help arrived. Two people helped me out. I saw the seriously injured being taken out. I waited until Joanne [McSorley] was taken out and travelled in the ambulance with her to hospital” (p. 43).

Suzanne Atkins was eventually “reunited with her daughter outside the station” (§17.68).

Amelia Tomlinson was taken directly outside and was driven to hospital by a man called Rob (pp. 14-15), who seems to be ETUK’s Robert MacFarlane.

Sarah Nellist drove herself home.

Andrea Bradbury and Barbara Whittaker took a taxi to GMP HQ.

Ashlee Bromwich was a P3 casualty who ended up outside Chetham’s School of Music.

Gemma O’Donnell was escorted out via the steps to the Fifty Pence area.

Summary

At least 25 of the 38 casualties who were taken to the Casualty Clearing Station can be identified from evidence published by the Inquiry.

It is possible that Adam Lawler, Evie Mills, Amy Barlow, Samantha Leczkowski, Caroline Davies, and Thomas McCallum accounted for some of the missing 13, but I have no evidence to confirm this.

It is also possible that a female evacuee with her husband was the first to arrive at the CCS, and that a girl with her father (not Eve Hibbert) was present at the CCS. If so, however, their identities are currently unknown.

It is frustrating only to be able to identify 25 of the 38 casualties who were taken to the CCS. This shows how successful the Inquiry has been in obfuscating key information. Hopefully, in due course, other researchers will be able to help fill in the 13 missing pieces of the puzzle.

Is the “38 Casualties” Figure Consistent With the Narrative?

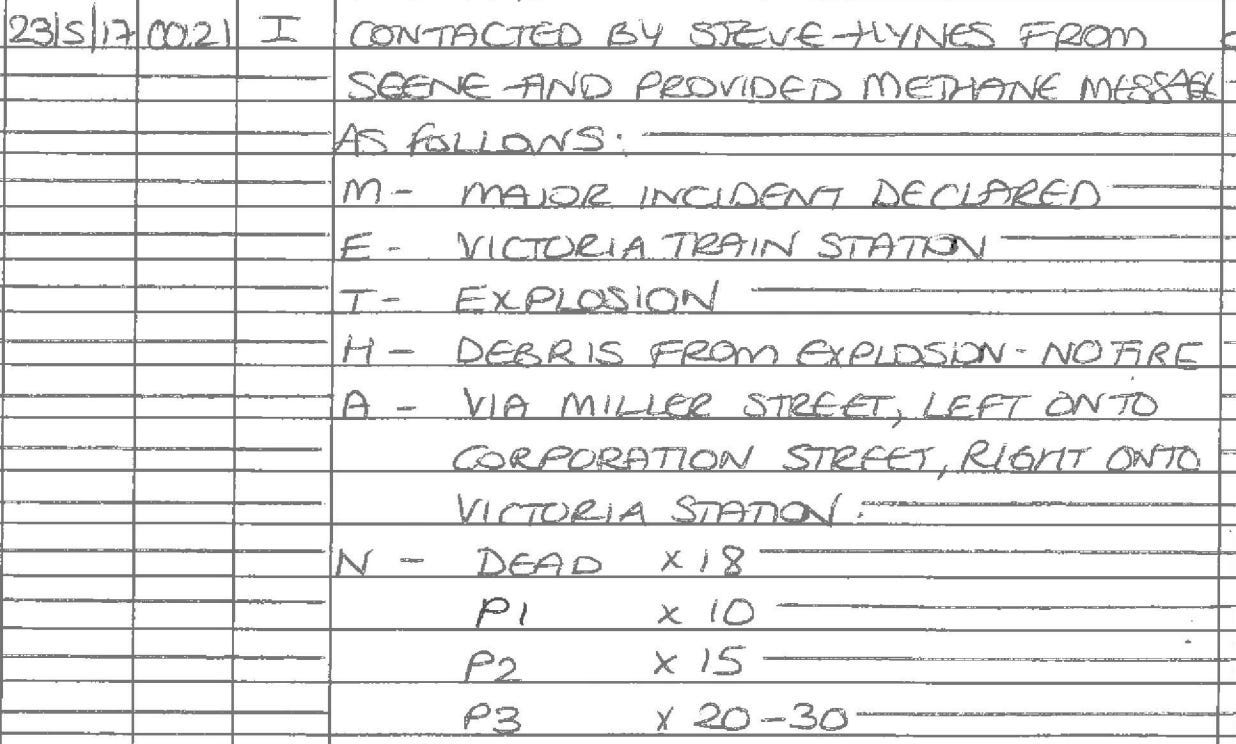

Paramedic Helen Mottram entered the Victoria Exchange Complex at 23:17:44. Having triaged all casualties, she counted “ten P1s and 15 P2s” and passed that information to Derek Poland, who was acting as loggist (pp. 33-35).

The CCS spreadsheet shows that the first 25 casualties did not arrive until 23:30. It is plausible that it took Mottram 13 minutes to complete her first round of triaging, at a rate of approximately two casualties a minute, given that she did not treat anyone.

That information appears to have made its way to NWAS Silver Commander Annemarie Rooney, who recorded the same figures in her Incident Decision Log at 00:21:

Source: National Archives

Rooney’s 18 “dead” figure makes sense at 00:21, given that Atkinson, Callander, and Roussos had been taken to hospital and Megan Hurley was not officially confirmed dead until 01:02.

Presumably, the “P1 x 10” and “P2 x 15” figures in Rooney’s log had not been updated to reflect the casualties who arrived at the CCS between 23:30 and 23:42.

In sum, it does appear that the above figures are consistent with the official narrative. Therefore, we might reasonably expect to be able to find out who the missing 13 casualties are.

Where Did Freya Lewis And Ruth Murrell Disappear To?

In terms of primary empirical evidence, only four casualties can definitely be located at the Casualty Clearing Station, namely, Claire Booth and Hollie Booth (see Pighooey (01:19:50) and Ruth Murrell and Freya Lewis (thanks to an Irish Sun article). There are plenty of redactions on the CCTV evidence encouraging us to believe that other casualties are present, but no actual evidence that they were.

In terms of Murrell and Lewis, questions arise regarding their time at the CCS, as Pighooey has demonstrated.

Freya Lewis

Freya Lewis was brought down to the CCS on a red trestle table:

Source: Irish Sun

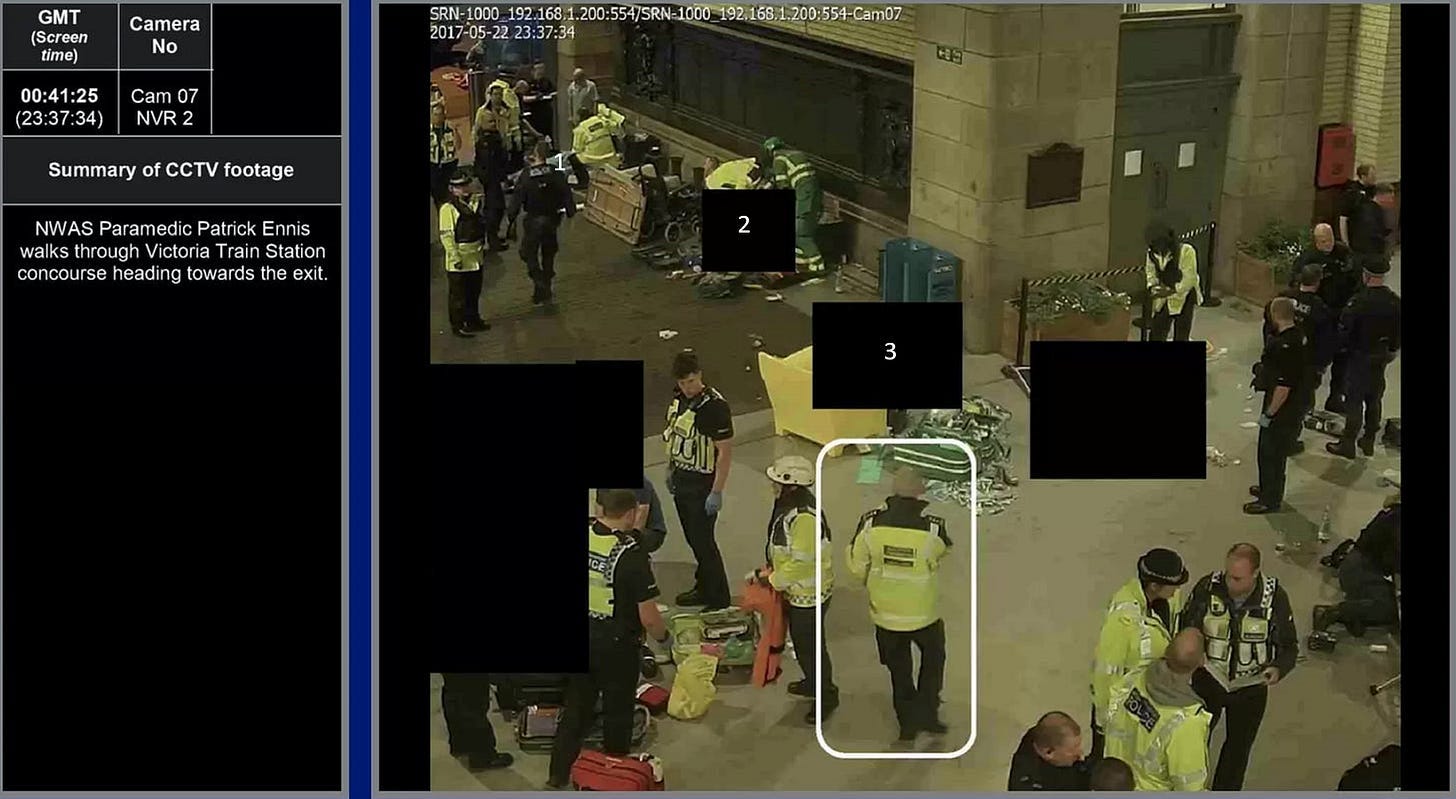

Pighooey (21:00) marks where the trestle table had been on the 00:41:25 CCTV image below.

Source: Pighooey (21:00)

Here, we see that Lewis, who was reportedly seriously injured having been close to Salman Abedi at the moment of detonation (see Part 18), had departed the scene by 00:41:25.

Yet, Pighooey demonstrates that Lewis’ departure time to hospital was 01:12. It seems unlikely, in an emergency situation, that it would have taken half an hour to load Lewis into the ambulance and for the ambulance to depart. Therefore, what happened to Lewis in the intervening half hour?

Ruth Murrell

Ruth Murrell is visible directly behind Lewis in the Irish Sun photograph above, yet is not visible in the same position at 00:41:25. It is possible that she had moved to one of the redacted areas.

By 00:57:50, however, there is definitely no sign of Murrell in the area seen in the Irish Sun photograph.

Source: Richplanet.net

We know from Pighooey’s analysis (13:44) that Emily and Ruth Murrell are Nos. 8 and 9 on the CCS spreadsheet, meaning that they did not leave for hospital until 02:35. This was one hour and 38 minutes later than the image above. So, where were they for that entire time?

Pighooey observes that, at 02:18 on May 23, 2017, Ruth Murrell spoke to Joanne Haslam at NW Fire Control and asked her to pass on a message to brother-in-law, Tim Murrell, as follows:

She [Ruth Murrell], and his niece Emily, were okay and were about to go into an ambulance. She told me that they were both hurt but being well looked after.

Where was she when that phone call was made? And where was Emily?

Ruth Murrell: The Plot Thickens

The same woman who I suggested may or may not be Ruth Murrell at the foot of the JD Williams steps in Part 18 seems to reappear in a similar location to Murrell at the CCS at 23:24:37.

Source: Richplanet.net, with my rectangular annotation in white

Here is the close-up:

Here is a reminder of the woman on the JD Williams steps:

To me, this looks like it could be the same woman, and thus it is tempting to identify her as Ruth Murrell. After all, what are the odds that a woman with a similar hairstyle to Murrell, wearing a similar outfit to Murrell (i.e., light top, trousers, beige shoes with a high heel), should be located — twice — in very similar locations to Murrell?

However, look carefully at the footwear. The footwear of the woman on the steps cannot be seen, because of the woman standing in front of her. But the woman in the chair appears to be wearing footwear with thick black soles.

Contrast that with the Barr footage showing Ruth Murrell walking around in footwear that has thick white soles:

Source of composite image: Hall (2020, p. 49)

Even though the foot of the woman in the chair is in shadow, one would have thought that a thick white heel cannot be made black, or at least darker than the rest of the shoe (unless there is some strange feature to do with cameras and lighting that I am unaware of).

We see the woman in the chair from her left, whereas the Barr footage captures Murrell from her right — could Murrell’s shoes have had soles that were white on the inside but black on the outside? It seems unlikely.

The woman in the chair only appears to have one foot on the floor, indicating that she may be sitting with legs crossed. But even if her right shoe were visible, which I do not think is the case, we would expect to see an obvious chunk of white, or at least a lighter colour than the rest of the outfit, judging by Murrell’s heel. We do not see this, however.

Finally, look at how high the heel comes up the foot of the woman in the chair: about half way to where the shoe meets the trouser leg. Then perform the same check on Murrell: the white heel comes up almost to her jeans. Therefore, we do not appear to be looking at the same shoes, or indeed the same woman.

The Empty Wall Area

Pighooey notes that, despite the clutter along the wall in the 00:41:25 CCTV image, there are few signs of any casualties there — I would say three at the most.

Source: Richplanet.net, plus my numbering in white

According to the CCS spreadsheet, only 10 casualties had left for hospital at that point, and they were the ones with the arrival times of 23:22, 23:22, 23:24, 23:25, 23:25, 23:28, 23:28, 23:36, 23:36, and 23:40.

Below is the same area according to the CCS floorplan.

Source: National Archives (snippet, with my annotation)

We can see from the floorplan that the wall seen in the 00:41:25 CCTV image is lined with some of the earliest casualties who arrived at 23:12, 23:12, 23:12, 23:13, 23:11, 23:07, and 23:08.

All of those casualties arrived before 23:22, which is the earliest arrival time of any casualty who had left for hospital by that point. Therefore, we should expect to see all seven P1 and P2 casualties still lining the wall.

Instead, we see only three. Where have the other four (including Freya Lewis and Ruth Murrell) gone? The 23:11 casualty arrived in a wheelchair, and there is an abandoned wheelchair in shot.

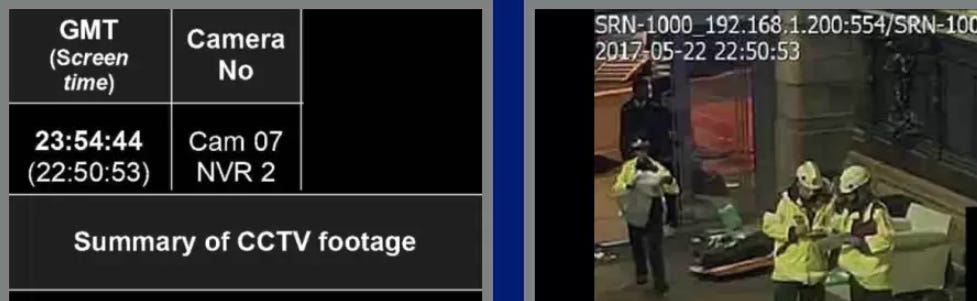

By 00:57:50, only one casualty remained by the wall.

Source: Richplanet.net, plus my numbering in white

I am confident that this last remaining casualty was Lucy Jarvis. We know from the Inquiry report (§17.26) that Jarvis was (alone on the night) placed on a stretcher. As shown on the CCS spreadsheet, the only casualty to arrive at the CCS on a proper (not “makeshift”) stretcher arrived at 23:08, and the floorplan places that casualty next to the entrance. CCTV imagery at 23:54:44 also shows a casualty on a stretcher next to the entrance. Who else could it be, if not Jarvis?

According to the CCS spreadsheet, the only additional departures to hospital between 00:41 and 00:57 were at 00:42 (arrived 23:18) and at 00:57 (arrived at 23:40). Their arrival times, judging by the floorplan, mean they were not by the wall. Therefore, where did two further casualties by the wall disappear to? All seven should still be present.

A peculiar feature of the CCS spreadsheet is that the first casualties to arrive at the CCS were among the last to leave. For example, of the first 13 patients to arrive, seven departed after 02:00. Of the remaining 25 patients, six departed after 02:00. It is not clear why this should be case, but it means that those lining the War Memorial entrance were, as a rule of thumb, officially among the last to depart.

In light of the evidence presented above, it is tempting to wonder whether some of them simply got cold/bored after an hour and a half of being on the floor and wandered off. To refute this suggestion, it is necessary to show where they went.

Loading Officer Matthew Calderbank’s Notes

One important evidence source that I have not seen anyone draw attention to are the notes made by ambulance Loading Officer Matthew Calderbank on the night.

Calderbank’s notes are significant for several reasons. For example, they give the total number of casualties taken to hospital as 59, which was the same figure given by Prime Minister Theresa May in her announcement on May 23, 2017.

Calderbank broke down the 59 hospitalisations, showing how many casualties, triaged as P1, P2, or P3, were taken to which hospitals:

Source: National Archives (INQ023259/3)

Calderbank’s notes include 21 casualties who do not appear on the CCS spreadsheet but who nevertheless were taken to hospital on the night. They are summarised below, according to their departure time to hospital, conveying ambulance call sign, and hospital (Hope is the old name for Salford Royal):

In sum, Calderbank’s notes help us to expand our horizons beyond the 38 who were taken to the CCS to the 59 who were taken hospital by ambulance or bus. We see that of the 21 additional casualties, 17 were P3, which makes sense.

According to the CCS spreadsheet, as worked out by Pighooey, Ruth and Emily Murrell were taken together in ambulance A544. Yet according to Calderbank’s notes, only one casualty was taken in that ambulance. What accounts for the discrepancy?

Like Claire and Hollie Booth, Ruth and Emily Murrell were, officially, both taken to Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital. Although both pairs were mother and daughter, would the mothers actually have been taken to RMCH, which claims to be “only for children and young people”?

It is reasonable to assume, in line with Calderbank’s notes, that a few P2s, and even a P1, could have ended up at the P3 collection area outside Chetham’s School of Music, particularly as they deteriorated over time. For example, Catherine Burke was upgraded from P3 to P2 while waiting there (p. 78).

Calderbank’s notes raise interesting questions around the “Stagecoach bus” that was allegedly used to transport 14 P3 casualties to hospitals in Bolton and Oldham. Jean Forster, in her witness statement, claims that she and her partner’s daughter’s friend, Laura, “were informed the walking wounded were to be taken to hospital by bus.” This appears to refer to Laura Anderson, friend of Millie Robson, who claimed to have been taken to hospital by bus. Student paramedic Simon Butler referred to “three double−deckers” that he thought took the walking wounded to hospital (pp. 125-126), although he was working on the station concourse and would not have seen them. Aliya Rule was reportedly taken to hospital in a “minibus” rather than an ambulance.

It is unclear which bus company (if any) was contracted to take P3 casualties to hospital. As far as I am aware, no bus company has taken ownership of having done so (which would be good for PR purposes), making it questionable whether any casualties were, in fact, taken to hospital by bus.

It is unclear when exactly the photograph below was taken, or what else would be seen were the camera to pan left or right, but the scene outside Chetham’s School of Music, where P3 casualties were sent, hardly appears drastic. At most, there are three or four casualties being attended to (not by paramedics), and they could have been injured in the stampede rather than in the City Room (see Part 15).

Source: Daily Mail

Why Was The Wait To Be Taken To Hospital So Long?

By 23:31 on May 22, 2017, i.e. at the end of the “Golden Hour” when the most critical interventions are made in an emergency, no casualty had departed for hospital.

By 00:01 on May 23, 2017 — i.e., one and a half hours post-detonation — only two casualties had left the Casualty Clearing Station for hospital (Callander and Atkinson).

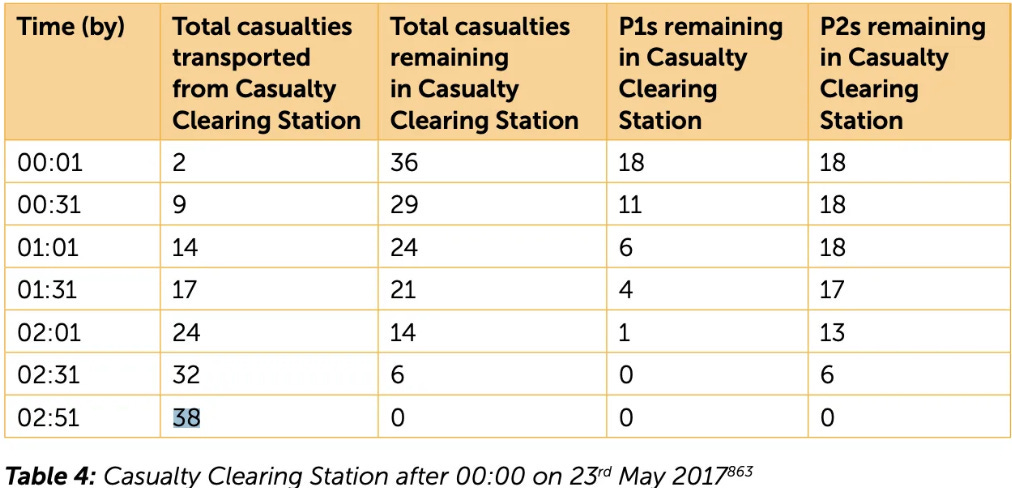

This rose to nine by 00:31, two hours after the bang. However, 11 P1 casualties (requiring immediate life-saving intervention) and 18 P2 casualties (requiring life-saving treatment within hours) still remained (§10.242).

Given that seven hospitals were 17-35 minutes away (North Manchester General Hospital 12 minutes, Manchester Royal Infirmary (MRI) 17 minutes, Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital 17 minutes, Salford Royal Hospital 18 minutes, Royal Oldham Hospital 29 minutes, Royal Bolton Hospital 30 minutes, and Wythenshawe Hospital 35 minutes, the fact that 11 P1 casualties and 18 P2 casualties had still not left the CCS two hours post-detonation requires explanation. Those times, which are ordinary drive times gleaned from Google Maps, can be cut by nearly two thirds for an ambulance with blue lights on: it took only six minutes, for instance, to transport Atkinson from the CCS to MRI (pp. 29-30). It took less than ten minutes to transfer 24 of the 38 CCS casualties (i.e., 63%) to hospital.

The final casualty, who was P2, did not leave the Casualty Clearing Station until 02:50, i.e., four hours and 19 minutes after their injuries were allegedly sustained (§10.242). On average, casualties remained at the CCS for two hours and four minutes before being taken to hospital. The average gap between the moment of detonation and arriving at hospital was three hours and ten minutes.

Average times, as calculated by a subscriber

The Inquiry report shows the flow of casualties from the City Room, via the CCS, to hospital as follows:

Source: Volume 2.1 of the Inquiry report

Saunders expresses concern about “the time it took to get patients to hospital” (§21.34), but he ignores the fact that 11 top priority patients — supposedly including Martin Hibbert, who claimed to have been bleeding everywhere, and his daughter, Eve, who he claims had a bolt pass through her head (see Part 7) — would likely not have survived a wait of over two hours (nearly three hours in their case) before being transferred to hospital.

When asked at the Inquiry how it could be that patients were waiting for hours to be taken to hospital, paramedic Joanne Hedges speculated that “it’s waiting for the hospitals to be cleared. It’ll be the only reason why any patient would have to wait” (p. 83). In other words, the hospitals first had to be ready to receive the casualties, and this may have involved mobilising additional resources (including extra doctors) in the middle of the night.

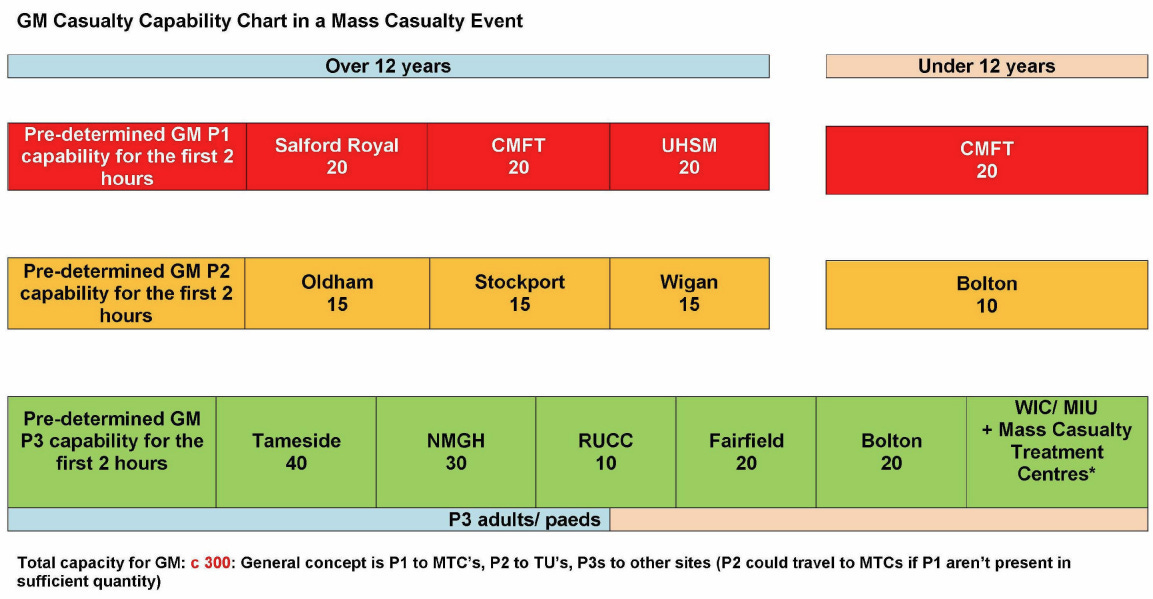

However, a certain “Ms Blackwell,” the barrister representing NHS England, made a pertinent point by drawing attention to a document by the Greater Manchester Combined Authority that shows the “framework for dispersal in a mass casualty event” (INQ008124/2). The second page of that document shows, in Blackwell’s words, “how many patients each of those hospitals could take at any point without any further advance notification” (p. 108).

Source: National Archives. CMFT = Central Manchester Foundation Trust (including Manchester Royal Infirmary and Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital). UHSM = University Hospital South Manchester (which operated Wythenshawe Hospital). RUCC = Rochdale Urgent Care Centre.

The key point to note is the “total capacity” figure in the bottom left, i.e. 300. The Greater Manchester hospital network was set up to be able to cope with 300 patients should a mass casualty event occur.

Only 59 patients were taken to hospital from the Manchester Arena, according to Calderbank’s notes, plus a few others who were taken by car. Therefore, there was ample capacity for hospitals to receive patients. So, again, why the long wait before casualties departed for hospital?

According to NWAS Medical Director, Edward Tun, only seven ambulances were free to treat people at the time of the incident, while 76 ambulances were responding elsewhere in Greater Manchester. By 23:15, he told the Inquiry, there were 25 ambulances available.

Yet, according to the CCS spreadsheet, the first 10 casualties departed by ambulance at 23:42, 00:00, 00:07, 00:08, 00:18, 00:24, 00:25, 00:27. 00:29, 00:36. Why, if seven ambulances were immediately available and 25 ambulances were available by 23:15, were casualties not being loaded straight into ambulances following triage?

Remember, the HART paramedics in the City Room had conducted primary triage of all casualties by 23:27. Helen Mottram at the CCS had triaged “ten P1s and 15 P2s” by 23:30. By then, ambulances had had one hour to arrive and must have been ready and waiting on Station Approach, despite Daniel Smith’s instruction that ambulances rendezvous at Manchester Central Fire Station two miles away, where they arrived between 22:50 and 23:02 (§10.83-10.84), before redirecting.

So, why did the flow of departures to hospital only begin in earnest around midnight, and why had only ten casualties left the scene by 00:36? Medically speaking, it makes no sense. Patients with supposedly life-threatening injuries were being left on the cold floor (not even given stretchers to lie on), and although Joanne Hedges claimed to have been pairing them up with ambulance crews (p. 50), those paramedics do not appear to have displayed any great urgency to get them to hospital. Why not?

The spectacle served up to the public by the legacy media. But why did the ambulances not depart sooner? Sources: Daily Mail, Manchester Evening News

Observations on the 00:40:57 CCTV Image

To my knowledge, no one so far has tried analysing any of the CCTV imagery captured by the camera below, which shows a significant section of the CCS along the station concourse (but not the sections in the War Memorial entrance or outside).

Below I have tried to match the 00:40:57 CCTV image to the relevant section of the CCS map, taking into account the fact that some of the casualties would already have left for hospital by then. I have retained the floorplan’s use of “11:39” instead of “23:39” etc. for ease of comparison.

Using the CCS spreadsheet to connect and arrival and departure times, the 11:25 arrival (highlighted in red on the floorplan) would already have departed, and it is possible that up to four more casualties (highlighted in yellow) may also have departed by then.

A few observations are worth making.

One of the 11:12 arrivals is sitting in a yellow chair, as the close-up below reveals. Could this be the first black casualty we have encountered? Or are lighting and pixelation playing tricks?

The other 11:12 casualty (not visible) is probably Freya Lewis, who we have established had vanished by around this time.

The stretcher where the 11:22 casualty was is empty, so that casualty probably departed at 00:27 or 00:29.

Pighooey has established that the 11:30 and 11:31 casualties are Hollie and Claire Booth, respectively.

Based on relative positioning, it looks as though the 11:40 casualty may still have been there, in which case the 02:10 departure time suggests it was Pauline Healy.

The four casualties in the top left of the CCS floorplan section above appear to have been drawn in the wrong position in front of the steps, rather than to the side of the steps, which would have placed them to the left of the other casualties had the floorplan been drawn right.

Below is a close-up of the area near the steps. There is one redacted area in the bottom left, suggestive of a casualty, and three people appear to be leaning over a potential second casualty. There is no evidence of additional casualties in this area, just an empty stretcher in the centre which may have been brought to move one of the two casualties.

If there are only two casualties in the image above, then the 11:24 and 11:28 arrivals must already have left for hospital, leaving the 11:16 and 11:33 arrivals present. The 11:24 and 11:28 arrivals would then be Atkinson and Callander, although this would contradict DCI Russell’s claim that Atkinson was “carried over to the war memorial” (p. 53), which is on the opposite side of the concourse.

A CCTV image from 00:54:39 appears to confirm that a casualty who was on a metal barrier was lifted onto the stretcher shown in the image above and wheeled out:

Finally, the full CCS floorplan shows some casualties above the white line below, which marks the end of the steps. I am particularly interested in the four casualties that I have highlighted, which arrived 11:42, 11:40, 11:40, and 11:31. There is no sign of the 11:31 arrival who, according to the CCS spreadsheet, should still be there, and the limits of the CCTV camera frame mean that the presence of the other three cannot be verified. They include Bradley Hurley, who officially arrived at 11:42.

Conclusion

Evidence regarding the Casualty Clearing Station further complicates the official version of events. Why was there no obvious distinction between P1 and P2 casualties in terms of who was taken to hospital first? Why is it so hard to find any evidence of casualties receiving medical treatment at the CCS? Why did the Inquiry try to conceal the identities of those taken to the CCS, even though 25 of the 38 can be identified from Inquiry documents alone (plus two others through cross-referencing against legacy media reports)? Why, after a three-year Inquiry, does the public still not know the identities of the other 11? Where did Freya Lewis and Ruth Murrell (plus two others) disappear to, long before their ambulances departed for hospital? Was there really a bus/buses that took casualties to hospital? Why were supposedly critically injured patients left to lie on the cold floor for hours?

At the end of this series, it seems reasonable to conclude that Richard D. Hall was persecuted by the British State for daring to conduct real investigative journalism into the Manchester Arena incident. His trial was clearly instigated by the Establishment, with the BBC leading the way. Martin Hibbert served as an entirely unconvincing vehicle through which to wage lawfare, and the High Court of Justice delivered a preposterous judgment that makes a mockery of the British legal system. The point of this was to intimidate other investigate journalists into not looking at the Manchester Arena incident and, indeed, into not questioning state power in general.

The only appropriate response to such tyranny is to keep the spotlight on Manchester. I am not an investigate journalist, but my open source analysis has confirmed that Hall had very good reasons to question what really happened on May 22, 2017.

The emergency service response looks like a coordinated stand down which could only have been orchestrated by the intelligence agencies. The fingerprints of MI5 and Counter Terrorism Policing are not difficult to detect across multiple aspects of the Manchester Arena incident, including potential operatives on the night.

The police investigation, Operation Manteline, appears to have doctored evidence, covered up other evidence, changed witness statements, and provided a narrative to the Inquiry based on highly selective “Sequences of Events.”

The Inquiry itself was anything but a “full, fair and fearless” investigation of the circumstances that led to the deaths of 22 people, as Saunders promised it would be [33]. Instead, it was a whitewash that kept the most important primary empirical evidence at arm’s length and worked to rubber-stamp a pre-determined narrative.

Primary empirical evidence does not support the official claim that there were 58 seriously injured people in the City Room, 51 of whom had to be carried to the CCS, or that Salman Abedi blew himself up. There is no credible way of locating where the 22 fatalities fell.

There is remarkably little official evidence relating to injuries. A statistically insignificant number of casualties can be found for whom significant injury detail is provided, yet the public has seen no primary empirical evidence to confirm those injuries, only a narrative containing multiple interlocking witness testimonies. This does not change the fact, however, that a TATP shrapnel bomb, by the logic of the Inquiry’s own “Blast Wave Panel of Experts,” would have caused far worse injuries, in terms of nature and scale, than those reported.

Correspondingly, evidence of active bleeding and pools of blood is extremely difficult to find, despite legacy media reports of the event having been a bloodbath. At most, there were a few faint “blood” trails on CCTV, plus evidence of certain casualties apparently bleeding through clothing (which could have been fake). But for some reason, barely anyone seems to have witnessed an active bleed, and even the witness testimonies in relation to John Atkinson, who officially bled to death, raise more questions than answers.

The Inquiry heard evidence from relatively few “survivors,” who appear to form a public-facing cadre, and it accepted uncritically any and every claim made by those individuals. The Inquiry offered scant indication of where those “survivors” were at the moment of detonation, and only six “survivors” can be found on CCTV imagery. Instead, the “survivors” were much more visible in the media afterwards, serving as a constant reminder to the public of the supposedly ever-present danger of terrorism.

The “survivors’” testimonies to the Inquiry appeared scripted and generally unconvincing. There were some peculiar commonalities among their testimonies that one would not expect to find, such as lack of pain/panic, highly unlikely physical feats, and a miraculous cheating of death. Ruth Murrell was not called to give evidence at the Inquiry, but her accounts elsewhere are starkly at odds with what we see her doing in the Barr footage.

Evidence of medical treatment being administered to scores of casualties is hard to find. First responders were not trained to deliver such treatment, the three paramedics who entered the City Room appear only to have triaged (and not treated) patients, and defibrillators were not use to shock anyone. Instead of treating seriously injured people, they were recklessly placed on metal barrier and trestle tables and carried precariously along the footbridge and down two flights of stairs, before being left on a cold floor. Although there is strong witness evidence available in relation to the treatment of Atkinson, Callander, and Roussos, those three cases do not serve as a representative cross-section of the casualties, and there is no primary empirical evidence in the public domain to support the witness accounts.

In the final analysis, the evidence strongly indicates that the public has not been told the truth regarding what really took place in the City Room on May 22, 2017. The incident may well have been a deep state fabrication, as Hall contends, for the purpose of generating “War on Terror” propaganda used to legitimise oppressive measures against the public.