Part 16 - Blood

Introduction

In Parts 14 and 15, we saw that primary empirical evidence supporting the official narrative around fatalities and injuries is weak to non-existent, despite the narrative itself being fashioned out of scores of mutually corroborating, and occasionally harrowing, witness testimonies.

When it comes to blood loss, the official narrative is much weaker. Claims of significant blood loss are primarily to be found in the legacy media. However, there is no evidence of blood pooling in the Barr footage or the Parker photograph, and in the Inquiry report, only 11 named individuals are to be found bleeding.

One of those named individuals is John Atkinson, who officially died from blood loss from his legs. Scrutiny of the Inquiry transcripts, however, reveals a surprising degree of ambiguity concerning the source and extent of Atkinson’s blood loss.

For some reason, it seems almost impossible to locate eyewitness testimony of active bleeding from an observed wound. Instead, casualties are to be found bleeding through clothing, or internally. Even at the Casualty Clearing Station, there does not appear to be any mention of active bleeding. This seems very peculiar for a mass casualty incident ostensibly caused by the detonation of a TATP shrapnel bomb in a crowded room full of people.

The City Room seems, from the available evidence, to be entirely free of blood spatter. Neither fake legacy media reports of Salman Abedi’s torso flying through the air, nor the debris generated by the detonation of Abedi’s device, provide any evidence of blood.

Potential blood trails visible on post-detonation CCTV imagery leading down to the Casualty Clearing Station also do not offer any convincing evidence of blood. They are too few, too faint, and there is no compelling reason to believe they show real blood.

The only two cases of alleged bleeding caught on camera (Amy Barlow and Ruth Murrell) both seem dubious.

Hall proposed that moulage and crisis actors were involved. Based on the evidence, that proposition deserves to be taken seriously. Not only does it fit the pattern of mock terrorist exercises leading up to the event, but it is hard to see how else to explain the radical disjuncture between the official version of events and what is clearly visible in the Parker photograph and Barr footage.

The Legacy Media and Blood Loss

The legacy media was keen to portray the Manchester Arena incident as a bloodbath.

For example, Kim Dick told the Sun on May 24, 2017, that Freya Lewis “lost pints and pints of blood in the time I was there,” while Philip Dick claimed “There was smoke and blood everywhere.”

There were media reports of people queueing to give give blood despite there being no appeal.

Source: The Sun

Martin Hibbert claimed in a Sunday Times interview of July 22, 2017,

there was a lot of blood. At that point I knew I was dying because the blood pool was just so big and I started shaking and going cold.

In ITV’s Manchester: 100 Days After The Attack, Hibbert claimed that he was losing blood from his left arm and neck “to the point that it was gathering in a pool.”

According to the Manchester Evening News on July 29, 2017, Joanne McSorley “suffered heavy bleeding from shrapnel entry and exit wounds around her stomach and groin.”

The BBC’s Manchester: The Night of the Bomb (May 22, 2018) features at least seven claims of blood:

Daren Buckley: “Blood hit the door, then just splattered, I remember having some on my face. […] I thought, well, where is it all from, this blood? Whose is it?” (10:10-10:43).

Eve Crossley: “My dad said, we can leave now, so we opened the door and there were [sic.] blood all over the [concourse] floor” (13:00). Her mother, Angie, confirmed that it was blood.

PC Jane Bridgewater: “The injuries were, if you can imagine, just holes, lots of holes, large holes, you found it difficult to stand up because of the slipping and the blood” (17:30).

PC Stephen Corke: “If you can imagine Hell, times it by a million […] I could taste blood […] This is where metal goes through flesh and bone like you cannot describe” (18:10).

Josie Howarth: “I could see blood coming down [her sister, Janet Senior’s] right shoulder, and I said ‘Janet, you’re hit,’ and she said ‘Yes, yes I know’” (24:20). Howarth claimed to have used her handbag strap as a tourniquet.

Police radio communications: “We’ve got massive blood loss. Massive blood loss to the chest” (37:40).

Robby Potter: “You could physically see the blood squirting out, and I thought, this ain’t good this [….] they tried using T-shirts on me to stop the flow, but it wasn’t stopping” (37:50).

A LADbible article from May 22, 2018, featured Martin Hibbert’s claim that “There wasn’t a part of me that wasn’t bleeding,” as well as BTP PC Jason Hague’s claim that

Blood was everywhere. In puddles on the floor, all over the walls, drenching the injured. There was literally a red tint in the air.

The BBC, on Feb 1, 2021, cited a member of the public, Rob Grew, who entered the City Room after the bang:

You look at those who are just lying there, bleeding out, and you have no idea what to do at all. So many injuries you’ve no idea where to start.

Grew reportedly “walked home covered in blood.”

Kim Dick told the BBC in February 2021, with reference to Freya Lewis: “This little girl just appeared. There was blood coming out of her mouth […].” She reportedly

managed to drag Freya towards the door of the foyer and lean her up against a wall. She knew she had to keep her upright to prevent her from choking on the blood which was still pouring out of her mouth.

Yet, photographic evidence shows Freya lying on her back at the Casualty Clearing Station with Kim leaning over her.

Source: The Irish Sun

Kim and her husband Phil also assisted another young girl, Aliya (presumably Aliya Rule, who attended the concert with Georgina Callander [p. 14]), who reportedly had leg injuries. “These girls were bleeding,” she claimed.

Lucy Jarvis told the Mirror on April 30, 2022, “I remember being on the floor and feeling really hot, but I didn’t think anything of it until I looked at my legs and saw all the blood.” She told the Inquiry “If he [John Clarkson] took my shoes off, I probably would have bled to death” (41:00).

Andrea Bradbury told the Sun on May 14, 2022, that she and Barbara Whittaker “had so much blood and glass in our shoes we were debating taking them off. I was covered head to foot in soot and blood.”

Clearly, with all this massive blood loss — blood spattering, blood coming out of mouths, legs, and feet, blood squirting out, victims losing pints of blood, bleeding out, blood pooling, the taste of blood in the air, first responders slipping in the blood, etc. — we would expect to find a very large amount of blood clearly observable in the primary empirical evidence.

So, what do we actually find?

Primary Empirical Evidence: No Blood Pooling

The alleged detonation of a TATP shrapnel bomb in a crowded room of over 300 people demonstrably produced very little evidence of blood, as we see in the Barr footage and the Parker photograph some 12-15 minutes post-detonation (see Part 14 for the timing).

Left: snip from Barr footage; right Parker photograph

Contrary to the blood and gore described by the legacy media, there were no pools of blood to be seen anywhere on the floor, and no indisputable evidence of serious injury.

Instead, there were some people lying on the floor, plus two red streaks which we are invited to believe came from John Atkinson (“At 22.31.08, as John Atkinson crawls along the floor, he can be seen to be leaving a large trail of blood behind him” [p. 7]).

Additionally, there are a few pieces of white gauze with red patches on them, the one in the foreground on the left having been casually thrown to the ground by Ruth Murrell (see Part 10).

John Barr claimed of the person next to him, who appeared to be injured:

a medical guy came around and looked at him and said right just hold that to your chest. (cited in Hall, 2020, p. 321)

Were red-stained pieces of white gauze being given to, or placed on, alleged casualties? Without the gauze, there are just people lying on the floor and others leaning over them.

Sources: Barr footage and Parker photograph

The Inquiry Report and Bleeding

It is noticeable that the words “blood,” “bleed,” and “bleeding” seldom appear in the Inquiry report in relation to specific casualties.

Blood and bleeding are not mentioned in Volumes 1 and 3 of the Inquiry report.

In Volume 2.1 of the Inquiry Report (Volume 2 being on the emergency response), only one named individual is identified as bleeding, and the only references to blood and bleeding are as follows:

The first two members of the public who dialled 999 at 22:32: “[T]here’s people everywhere, blood everywhere” (§14.12). “There’s loads of people bleeding” (§13.141)

“Ronald Blake noticed John Atkinson lying on the floor covered in blood” (§16.169).

PC Jessica Bullough at 22:34: “[W]e are going to need ambulances as well, we have a female bleeding — much blood” (§13.10).

Shortly after entering the City Room at 22:42:47, Ryan Billington broadcast a message over the ETUK radio channel […]: “This is a major incident. Follow major incident protocol. If people have no pulse, we can’t help; treat catastrophic bleeding” (§16.104).

Patrick Ennis at 22:57: “Basically, at the moment it’s going to be providing first aid […] to those that are bleeding heavily” (§14.129).

Unarmed GMP officers “had received no training in life-saving interventions, such as stopping catastrophic bleeding or opening an airway” (§12.356).

In Volume 2.2 of the Inquiry report, bleeding is mentioned in relation to named casualties in six sets of “survivor” testimonies:

Lucy Jarvis “was losing a lot of blood. Millie Tomlinson tied her jacket around Lucy’s leg to try to stop the bleeding” (§17.25).

“Dr Burke and his wife were bleeding from their legs. Dr Burke had shrapnel injuries to his right leg and left buttock. His wife had shrapnel injuries to her thigh and heel. His daughter’s right arm and leg were bleeding heavily, as was the right side of her head. Dr Burke took off his shirt and tied a tourniquet around his daughter’s arm and a coat around her leg” (§17.37).

Josephine Howarth’s “leg was badly injured, and there was blood gushing from it” (§17.47). “Janet Senior and Josephine Howarth were both seriously injured. Josephine Howarth told her sister to use her handbag strap as a tourniquet” (§17.49).

Martin Hibbert “noticed he was losing a lot of blood” and Eve Hibbert “was bleeding and gasping for breath” (§17.54-17.55).

Hollie Booth “had lost so much blood that she needed a blood transfusion at hospital” (§17.84). Her mother, Claire Booth, told the Inquiry that Hollie had been “left for 3.5 hours to bleed” (p. 128).

Bradley Hurley “could not move and was bleeding heavily” (§17.91).

The reliability of “survivor” testimony will be dealt with in Part 17.

Bleeding is also mentioned in relation to Atkinson, whose “leg injuries were associated with severe compressible bleeding” [§18.162]), and Roussos (“internal bleeding” [§18.192]). There are numerous references to bleeding in the sections relating to “survivability” for Atkinson and Roussos.

Over half the references to blood in Volume 2.2 come in three sections titled “Blood,” “Freeze-dried Plasma,” and “Tranexamic acid [TXA]” (pp. 115-117). These make the case that it is not practicable to equip all ambulances with blood, and that it would be better to ensure that mobile resources (e.g. air ambulances) are on hand with staff suitably qualified and equipped to transfuse blood. The case is made for HART paramedics to carry freeze-dried plasma, which has the potential help those with catastrophic blood loss even though it does not carry oxygen. Saunders recommends that a review be carried out into whether frontline ambulances should carry intramuscular TXA, which helps blood to clot.

In sum, across the 1,346 pages of the Inquiry report, which ostensibly investigates a mass casualty event, a maximum of 11 named individuals can be found bleeding. They are: Lucy Jarvis, Darah Burke, Catherine Burke, Josephine Howarth, Janet Senior, Martin Hibbert, Eve Hibbert, Hollie Booth, Bradley Hurley, John Atkinson, and Saffie-Rose Roussos.

The Inquiry was clear from the beginning that it sought to minimise reference to injury detail in order to avoid causing unnecessary alarm and distress (see Parts 13 and 15). That said, it means that there is very little positive evidence available to the public of named victims actively bleeding.

The Case of John Atkinson

The Official Cause of Death

The official conclusion of Dr Naomi Carter’s post-mortem examination of John Atkinson was that he

died principally of the effects of blood loss from his leg wounds. (§18.156)

The Blast Wave Panel of Experts, after allegedly being provided with CCTV and body-worn camera footage, found that Atkinson’s leg injuries were

associated with severe compressible bleeding. The video demonstrates catastrophic and continuing external bleeding […] (§18.162)

Who Saw The Stills?

According to Sophie Cartwright QC, first-hand sight of blood in the evidence was only available to “those who have been able to view the stills” (p. 101).

John Cooper QC told Saunders, in relation to the amount of blood that Atkinson was losing,

I’m reassured that you have seen certain images, sir, which we asked of you. Thank you. (p. 74)

This suggests that the Chairman, the legal team, and possibly Atkinson’s family had seen those images.

So too, it seems, had certain witnesses, viz. the following exchange between Saunders and ETUK’s Ryan Billington:

Q. The real thing is we have heard about a lot of blood. We have seen the pictures. You have seen the pictures.

A. Yes. (pp. 126-127)

The public has not seen the pictures.

Evidence Given During the Inquiry Does Not Match Claims of Extensive Blood Loss

Although the public was denied access to the primary empirical evidence allegedly seen behind closed doors, the evidence given during the Inquiry hearings does not support Atkinson’s “catastrophic bleeding,” as John Cooper QC referred to it (p. 78).

In a 999 emergency call made 52 seconds after detonation, Ronald Blake (a member of the public) described Atkinson as being “really injured and with blood pumping from his leg” (p. 9). Yet, although Atkinson is officially said to have been bleeding heavily from both legs, Blake for some reason did not see any bleeding coming from Atkinson’s left leg (pp. 63-64). Nor did Gareth Chapman, another member of the public, who adjusted the tourniquet that Blake had applied (p. 15).

Ronald Blake. Source: BBC

Another member of the public, Robert Grew, crouched next to Atkinson between 22:48:50 and 22:50:33. In a witness statement dated November 11, 2020, Grew describes Atkinson as

bleeding heavily from his leg [singular], which had a T−shirt tied around. I checked around for something I could use as a tourniquet, but nothing was immediately evident. Clearly, the T−shirt was ineffective and he was losing a lot of blood. (p. 17)

Grew’s recollection, however, is contradicted by Ryan Billington, who approached Atkinson nine seconds later, at 22:50:42. Billington told the Inquiry that

At the time of my assessment, when I put my eyes on John, he had no active catastrophic bleed at that moment. By that, I mean there was no bleed that was actively bleeding, spurting or pouring blood which needed immediate intervention. (p. 101)

Billington was insistent that “the bleeding was fully controlled” (p. 103), that Atkinson “wasn’t catastrophically bleeding” (pp. 132), and that “all bleeding from his limbs was controlled,” i.e., “he wasn’t actively bleeding” (p. 146). Atkinson was fully clothed at that point and Billington did not cut away his clothes (p. 102).

Billington claimed in his witness statement dated August 4, 2021, that he slipped on Atkinson’s blood, but he was not asked about that at the Inquiry. When John Cooper QC tried to get Blake to corroborate it, Blake replied “I don’t know” (pp. 78-79).

Cooper also asked Blake the following questions about Billington:

Q. […] Did he say anything to you about what he saw of John’s wounds?

A. I don’t recall, no, nothing being said.

Q. Did he give any acknowledgement to anyone, “Goodness me, there’s so much blood here, I’m slipping over it, we must help this lad”?

A. No.

Q. Nothing at all?

A. No.

Q. Did he seem concerned in any way over and above, of course, the general tragedy?

A. No. (p. 79)

The Sequence of Events for Atkinson includes many people participating in his care. Cooper asked Blake:

Q. For all those people coming and going, whether it’s the police, whether it’s British Transport Police, whether it’s ETUK, from what you saw, no one actually communicated with each other and said, “He’s catastrophically bleeding, we need to get him to hospital now”?

A. No. (pp. 83-84)

When paramedic Patrick Ennis came over briefly at 23:12:08, as he was triaging casualties, he attended to Atkinson’s friend, Gemma O’Donnell (who was well enough to be assisted out of the room) but did not look at Atkinson (p. 85). How could he have missed the “catastrophic bleeding” (p. 78) that meant Atkinson had left “an obvious trail of blood behind him” (§18.72)?

ETUK’s Marianne Gibson is cited repeatedly in the transcripts as having attended to Atkinson, yet in a witness statement date July 28, 2021, she claimed to have “no specific recollection of John or giving him assistance” (p. 30). She claimed in the conditional tense that “cutting clothes off would have been done as part of her casualty assessment” of Atkinson (p. 31), but not that she actually cut his clothes.

Yet, according to the official record, at 23:12:13, “John’s exposed torso and legs can be seen more clearly” (p. 29), and at 23:14:18, “John’s clothing has been removed, dressings can be seen to have been applied to both of his legs […]” (p. 31). It is not clear who applied the dressings, but we are invited to believe it was Gibson, who was seen with a red first aid kit at 23:10:56 (p. 28). This means that she would have seen active bleeding from both of Atkinson’s leg wounds, but strangely she has no memory of this.

According to the Inquiry report,

In order to help stem blood loss, police issue “leg restraints” were also applied around the top of both of John Atkinson’s legs approximately 43 minutes after the explosion. (§18.73)

However, PC Michelle Johnson (BTP) “only recalls applying one [leg restraint] to John’s leg but cannot be sure” (pp. 33-34, my emphasis).

So far, no eyewitness has reported seeing Atkinson bleeding from both legs, as would be necessary to explain the two red streaks in the Parker photograph. As Sophie Cartwright QC put it, “there was bleeding not just from his right leg but also from his left leg and that’s what the trail behind him suggested” (pp. 106-107).

Like Blake before her, Johnson was unable to identify the source of the bleeding, even though Atkinson’s legs were now exposed: “I recall he had blood coming from his legs, but couldn’t see exactly where it was coming from” (p. 33). And again: “I can’t recall exactly where he was bleeding from, it was kind of generally on his legs” (p. 154). Nor could she recall whether there was a significant amount of blood on the ground (pp. 156-157), even though Atkinson had supposedly been suffering catastrophic blood loss for almost three quarters of an hour.

At 23:17:58, according to DCI Russell, Atkinson was taken on a display board towards the exit doors to Victoria Station, leaving “a trail of blood along the route” (p. 41). If so, however, there was no obvious sign of that trail on CCTV:

Composite of post-detonation CCTV imagery. Source: Hall, Manchester on Camera (48:30)

When Sophie Cartwright QC asked Blake about “the trail of blood wherever John was taken,” he had no recollection of it (p. 72).

At the Casualty Clearing Station, the nature of Atkinson’s injuries did not become any clearer, judging by the following exchange between Cooper and Blake:

Q. Did they ask, for instance, what his injuries were?

A. No.

Q. Was John still bleeding out heavily at the time?

A. He was still bleeding, yes, but I couldn’t see how —

Q. So the paramedics simply want John’s name and that was it?

A. While they were assessing and then that’s when others came over and I went outside.

Paramedic Michael Ruffles claimed he “could not visibly see the injuries to John’s legs but there was no active haemorrhage, possibly due to tourniquet and dressings. All the dressings were left in place” (p. 167).

Thus, not one eyewitness was able to specify the source of Atkinson’s “catastrophic bleeding”; it just seemed to be coming through his trousers until dressings were applied without anyone recalling seeing any wounds. Blake, Chapman, and Grew claim to have seen blood but no wound. Johnson “couldn’t see […] where it was it coming from.” Billington and Ruffles denied that Atkinson was actively bleeding, and Ennis saw nothing to concern him, nor did ETUK or BTP. Gibson claims to have no recollection of Atkinson. There is no primary empirical evidence of Atkinson trailing blood from his makeshift stretcher across the City Room to the doors to the footbridge.

So, whilst it is possible that CCTV and body-worn camera footage may exist showing Atkinson’s catastrophic blood loss, as well as the corresponding post-mortem report, not only is that evidence not in the public domain, but at least eight eyewitnesses (including two paramedics and a first aider) failed to identify the sources of Atkinson’s bleeding or even that he was bleeding from both legs. This hardly offers the public reassurance regarding the nature and extent of Atkinson’s injuries.

Where Was The Blood Coming From?

Bleeding Through Clothing

Blake was unable to specify the source of Atkinson’s bleeding:

I remember seeing the blood pumping through John’s trousers, but don’t remember seeing any wounds and where it was coming from. (p. 14)

He claims to have applied an improvised tourniquet using his wife’s belt, presumably over the top of Atkinson’s right trouser leg, to which Gareth Chapman later added a T-shirt.

This was not an isolated case. Amy Barlow, in Manchester: The Night of the Bomb (15:13), is shown outside the Arena, her legs being held in an elevated position, with blood ostensibly dripping through her trousers onto the floor. In the clip, a man can be heard saying “tie it up with a T-shirt, don’t take nothing off.” Again, we are looking at bleeding through clothing.

In the case of Hollie Booth, when a T-shirt was pressed against her leg, “Hollie’s jeans started to go a deeper red with more blood” (§17.78). More bleeding through clothing.

Internal Bleeding

At 23:05:27, PC Danielle Ayers (BTP) claimed of Kelly Brewster that “She doesn’t appear to be bleeding anywhere,” to which Ian Parry replied that “It may be internal” (p. 11).

In the case of Saffie-Rose Roussos, off-duty nurse, Bethany Crook, told the Inquiry “I could not see where the blood was coming from” (pp. 37-38). According to member of the public, Paul Reid, ETUK’s Marianne Gibson “cut off Saffie−Rose’s leggings to look for bleeding but could not see any” (p. 16). Gibson told the Inquiry “I didn’t see any pools of blood” (02:37:00). This seems to have been because of internal bleeding. Paramedic Gillian Yates, for example, thought that “most of the blood loss was internal haemorrhage due to fractures and shrapnel wounds in her legs” (pp. 80-81). Only “about 50mls of blood” were left behind on the stretcher (p. 150).

The Greater Manchester Combined Authority stated “The evidence of witnesses who attended to Saffie was consistent: they saw no evidence of bleeding to indicate the application of a tourniquet.”

At Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, Dr Mohammed Ibrahim (consultant anaesthetist) told the Inquiry,

I don’t remember like pooling of blood or a significant, serious amount of blood [in the case Roussos]. There was a little blood and bruising over the thighs and in different parts of her body, but I don’t remember exactly that there was a massive amount of blood. (p. 254)

For some reason, Saunders felt the need to explain why Roussos “did not die sooner through blood loss” (§18.208).

Lack of Active Bleeding at the Casualty Clearing Station

Of the “survivors,” Lucy Jarvis, Josie Howarth, Janet Senior, Martin and Eve Hibbert, Claire and Hollie Booth, and Bradley Hurley were all evacuated as P1 or P2 casualties to the Casualty Clearing Station. There is also Emily Murrell, who “lay in Victoria Station until after 2 am in the morning, all the while losing blood” (p. 74).

Reading the descriptions of their injuries above (“losing a lot of blood,” “blood gushing,” “bleeding heavily,” “needed a blood transfusion”), there should, presumably, have been multiple testimonies from paramedics at the Casualty Clearing Station regarding catastrophic blood loss.

Instead, student paramedic Simon Butler, who arrived at 23:10:22 and was present at the casualty clearing station until around 02:30:00, told the Inquiry

I don’t recall seeing anyone in the concourse area who had a large active bleed […] There’d obviously been significant bleeding from the clothing and I saw blood on the floor in the concourse area, but I didn’t see a patient actually actively bleeding. (pp. 122-123; 44:50)

This, again, is consistent with the idea of bleeding through clothing and blood allegedly on the floor, but not with eyewitness testimony of having witnessed an active bleed directly from a wound.

Senior paramedic Joanne Hedges believed she had seen active bleeding at the CCS:

Q. Were there patients that arrived in the casualty clearing area who had active bleeding but had not had tourniquets applied?

A. Yes. I believe so.

Q. Again, those patients, what happened with those patients?

A. Two of them had police officers with them, who were then putting on pressure to the area while crew then were allocated immediately (p. 75).

However, she did not see active bleeding directly from a wound, just police officers applying pressure to an area.

Paramedic Helen Mottram was asked about dealing with catastrophic bleeding at the Inquiry:

Q. Just so it’s clear, it was a part of your triage role, is this right, to apply tourniquets where they needed to be in relation to catastrophic haemorrhage?

A. Correct.

Q. You also in your notes refer to something called TXA. Is that tranexamic acid?

A. It is.

Q. Is that also something that can be administered to deal with catastrophic bleeding?

A. It can, yes. (p. 56-57).

However, Mottram went on to state that she did not actually treat any casualty and that she did not administer any TXA (pp. 57-58, 67).

To reiterate, in over three hours spent at the Casualty Clearing Station following the alleged detonation of a TATP shrapnel bomb in a room full of people, these three paramedics offer no concrete evidence of any active bleeding, let alone catastrophic blood loss, having occurred. Why not?

The Severed Torso Myth

If we are to believe legacy media reports, a large amount of blood should have been generated by Salman Abedi’s severed torso and entrails flying through the air after he blew himself up.

The Sun, on May 28, 2017, featured Darron Coster’s claim that “It looked like he [Abedi] had been blown inside the doors. I didn’t want to look. His torso was through the doors and he had no legs.” We know this to be untrue (see Part 11).

Daren Buckley claimed in the BBC’s Manchester: The Night of the Bomb that

We seen the bomber he were just erm literally ripped in two cos I remember seeing his guts on the floor and stuff, do you know what I mean, but there was no top part of a body.

Again, there is no evidence to support this sensationalist claim: no entrails or blood pooling in the Barr footage, for instance, or people reacting in horror.

A third member of the public, David Lambert, told the BBC:

As we were going out, we looked to our left, and we saw half a body, or a torso or something. […] We walked past where the merchandise stand had been earlier on […] (cited in Davis, 2024, pp. 226-227)

Lambert also claimed to have seen “body parts everywhere” as he left the Arena and entered the concourse. Yet, we can see from CCTV footage that there were no body parts or blood on the concourse outside the City Room (see Part 11), and we know that the merchandise stand was undamaged.

Andrea Bradbury told the Sun in 2022:

His arms went this way and his legs that way and Barbara [Whittaker] watched his torso flying over her head. Shrapnel was flying out at different angles and you could hear the pieces scuttling along the floor, and my legs felt they were being hit by garden strimming wire.

Bradbury and Whittaker were by the merchandise stall at the moment of detonation. If Abedi’s torso flew over their heads, it would have ended up somewhere in the top right quadrant of Hall’s post-detonation composite image below. Evidently, it did not do so, nor is there any sign of shrapnel all over the floor. Therefore, there is no reason to treat any element of Bradbury’s account as reliable.

Source: Hall, Manchester on Camera (48:30)

What Was The Debris On The City Room Floor?

Camera phone footage shows that there was debris of some description on the City Room floor, although evidently not “nuts and bolts.” What was it?

Source: New York Times

Snippet from Hall’s composite image extracted from the Barr footage. Source: Hall, Table For Two (30:55)

Eye witness testimony gives us a better idea of where the black material on the floor may have come from.

According to Joanne McSorley, following the bang

There wasn’t a sound. It was an eerie silence and I had also never experienced that type of silence before. I could see stuff floating down in the air in a grey swirl […], small pieces of something on fire or singed around the edges within this swirl. (pp. 22-23)

Philip Dick recalled “There was smoke and ash, which looked like black leaves in the air” (p. 2).

Sarah Nellist told the Inquiry “he detonated the bomb — I saw him — the only way I can describe it, it was like black powder paint” (p. 39).

Thus, the black debris on the City Room floor was evidently generated by the device itself as it detonated. Perhaps Abedi’s rucksack was blown into small pieces. Perhaps, if Hall and Davis are correct that a pyrotechnic device was involved, the singed black ash/leaves/powder were generated by it. At any rate, we must be careful not to confuse that material with blood.

“Blood” Trails

The Inquiry released 806 CCTV still images. These include many post-detonation images. Many are heavily redacted, but there are also some which are not.

In particular, there are CCTV images of the City Room, the footbridge, and the station concourse which contain only minimal redactions and collectively show most of the floor area.

Given that 38 P1 and P2 casualties were evacuated to the Casualty Clearing Station, with some later reporting extensive blood loss, and that P3 casualties (the “walking wounded”) also crossed the footbridge, for a total of 59 people taken to hospital, we should expect to find significant evidence of blood along the route, notwithstanding tourniquets and bandages applied in the City Room.

Instead, we find the opposite, as the CCTV images below show.

The source for all the images below is Richplanet.net. The images are best viewed on the Richplanet viewing app and on a large screen to be able to see the level of detail necessary. The white box annotations of marks on the floor are mine.

The Footbridge (Looking From the City Room)

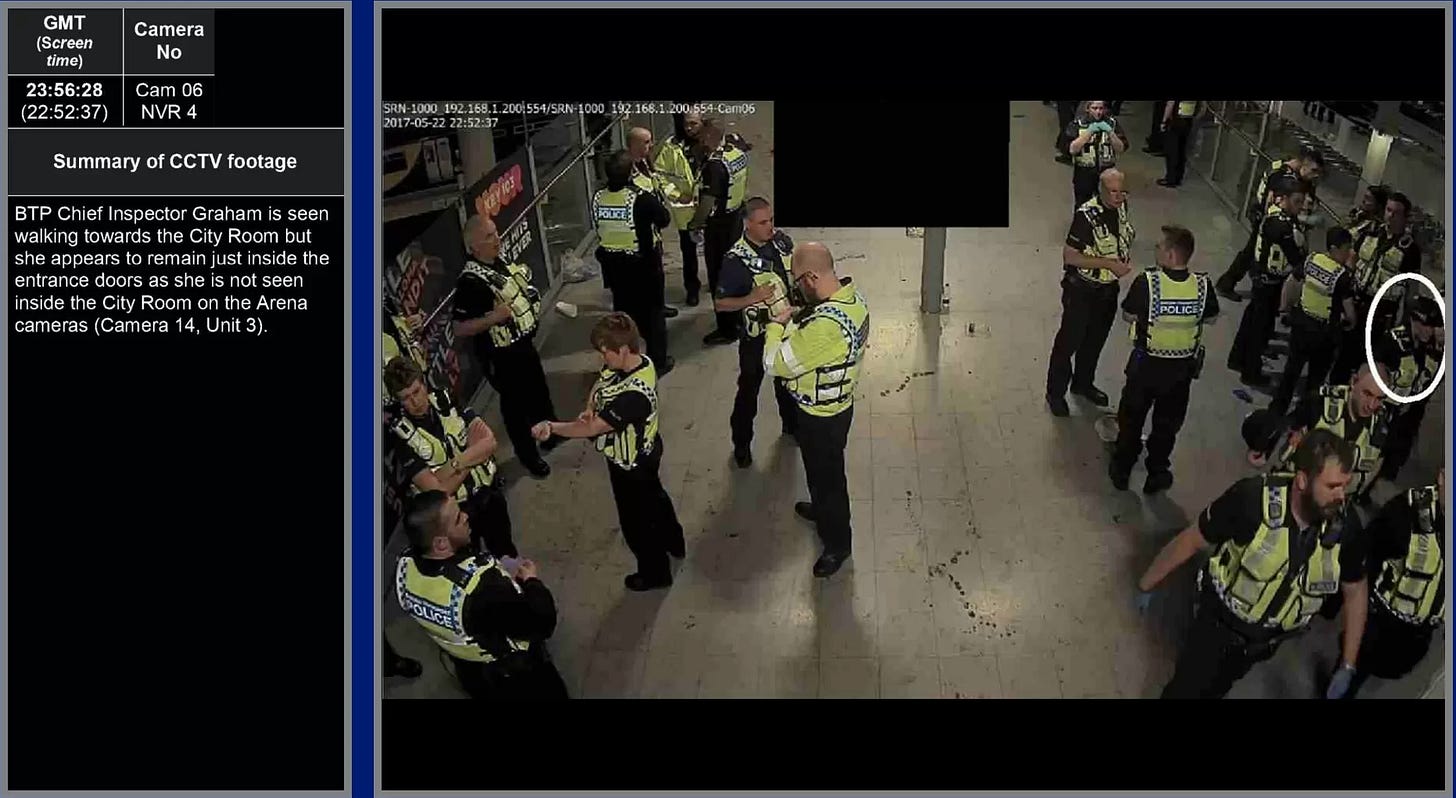

The last casualty was evacuated from the City Room at 23:39. But at 23:56:28, there is minimal evidence of blood on the footbridge just outside the City Room. There are just a few drops of something down the middle:

Source: Richplanet.net

That tiny amount of evidence was redacted in the 00:17:40 image below. I have also highlighted areas where there appears to be evidence of other marks on the floor. If it is blood, then it has not been redacted, the droplets are not as large as in the redacted areas, and they do not appear to have been smudged by the officers’ boots. Therefore, it is probably not blood.

Towards the Bend in the Footbridge

Moving further down the footbridge, looking towards the bend, we see that it was completely clear at 22:12:02, pre-detonation:

At 22:51:17, some minor marks are visible in the bottom left, bottom centre, and right of the image:

The 23:00:36 image below shows four areas of marking to the floor. Inspector Michael Smith was taking the decision to evacuate casualties to the CCS around that time (§13.429), so those marks will not be blood from seriously injured patients.

Once the evacuations to the CCS had taken place, only two small areas were redacted in the 23:47:01 CCTV image (suggesting possible blood), although police officers are standing in the areas marked in the image above.

The other post-detonation images from this camera are all blacked out left of the lamppost in the foreground.

Looking Towards the Top of the Steps Down From the Footbridge

Another CCTV camera close to the bend in the footbridge captures the area before the steps leading down to the station concourse.

At 22:36:39, over six and a half minutes after the official detonation time, there was no sign of blood in that area of the footbridge.

A trail of some description appears at 22:51:54:

Another trail has appeared by 23:25:02:

At 23:56:00, with all casualties having been evacuated to the CCS, no further possible trails have appeared:

Looking Back Towards the City Room

Looking in the opposite direction, back towards the City Room, we see that the floor area was pristine at 22:16:59, pre-detonation:

Within the first minute of detonation, at 22:31:57 a possible blood trail appears on the right-hand side of the footbridge. 57 seconds after the official detonation time, we see seven or eight people walking towards the City Room and two others standing sideways, but no one fleeing towards the camera.

At 22:32:02, two possible blood trails can be seen on the right and left:

Fast forward to 23:30:42, and only a couple of extra marks have appeared:

The next image, from 23:46:48, by which time all casualties had been evacuated to the Casualty Clearing Station, reveals that the lower marks in the image above form part of a trail:

Thus, on this section of the footbridge, only two potential blood trails appeared during the evacuation to the Casualty Clearing Station.

As noted in Part 11, despite ETUK’s Ian Parry and Ryan Billington both referring to “catastrophic bleeding” at the Inquiry (§16.102-16.104), CCTV footage shows ETUK staff leaving the scene with no obvious signs of blood on their uniforms:

The Steps to the Train Station Concourse (Top)

Below is the last available pre-detonation image of the top half of the steps leading down to the train station concourse:

Post-detonation, at 22:37:51, some additional marks have appeared:

By 23:31:21, two further trails have appeared either side of the centre hand rail, one quite pronounced:

Based on the above images, it would appear that six different sets of marks were left on these steps, four of them within the first seven minutes post-detonation, and two others during the evacuation of casualties to the CCS.

The Steps to the Train Station Concourse (Bottom)

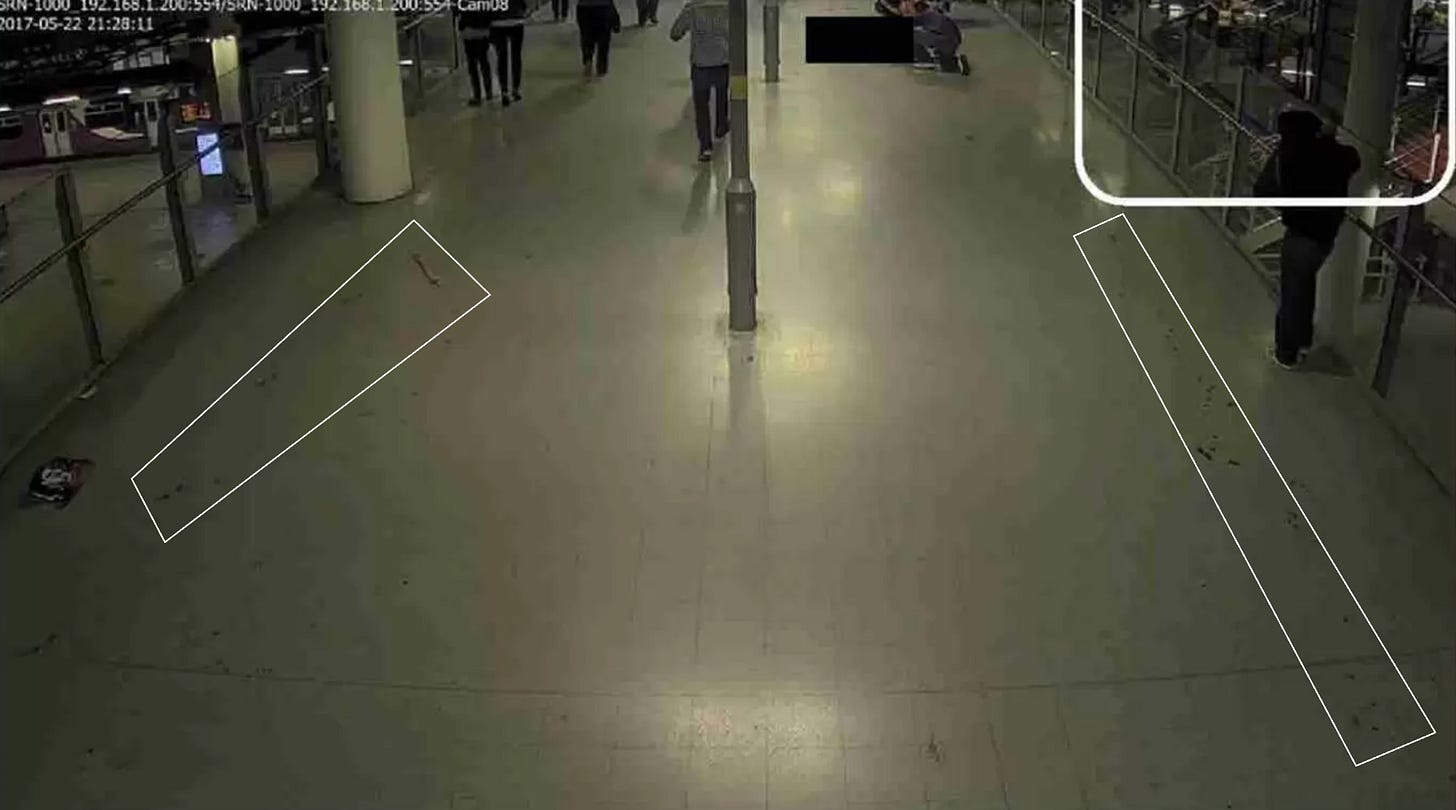

The image below, captured at 23:13:10, shows no evidence of blood from any of the nine patients hitherto evacuated to the CCS on around the steps at the bottom of the footbridge to the City Room:

Source: Richplanet.net, with my annotation in white

29 seconds later, however, there does appear to be some potential evidence of blood in the area I have highlighted in white:

Source: Richplanet.net, with my annotation in white

According to the official evidence, the only casualty to have arrived at the CCS at 23:13 was also the only casualty to have walked there, which we know from Pighooey’s evidence to be Ruth Murrell (13:44). Therefore, did Ruth Murrell leave the above trail?

At 23:46:14, four minutes after the last casualty had arrived at the CCS, a single trail can faintly be seen on the steps (again best viewed on the Richplanet app on a large screen):

The evidence indicates that only two people “bled” on the lower flight of steps or in front of them all night. Remember, 59 officially were taken to hospital.

The Station Concourse

Pre-detonation, at 22:01:55 (the times shown on the CCTV images themselves are wrong), the floor area at the centre of where the Casualty Clearing Station was set up was pristine:

By 22:38:10, a trail had appeared, though it is unclear where from:

By 23:03:17, a few more marks are visible:

Below is the same area at 23:54:44, twelve minutes after the last casualty arrived at the Casualty Clearing Station. It shows no signs of blood, although these may have been redacted:

I can find no further CCTV evidence of blood in the Casualty Clearing Station area. Readers are encouraged to select “Station” in the “Areas” section of the Richplanet app and to scrutinise the images for themselves.

Summary

Considering the legacy media’s portrayal of the Manchester Arena incident as a bloodbath, there is astonishingly little blood to be found in the CCTV evidence en route to the Casualty Clearing Station. I have plotted the sum total of evidence of possible blood trails in red in the diagram below.

Unannotated Source: Volume 1 of the Manchester Arena Report, Figure 14

In principle, all of that evidence could have been generated by just a handful of people: one walking or being assisted/carried along the left of the footbridge, one on the right, plus a few others.

Past the bend in the footbridge, there are only two trails, and on the lower flight of steps to the station concourse, as well as the CCS area, there is only one. Again, 59 people were taken to hospital, 38 of which were P1 or P2, requiring urgent treatment.

Given that a TATP shrapnel bomb had allegedly detonated in a room full of hundreds of people, and that “survivors” and first aiders alike reported “catastrophic bleeding,” and that there were not enough tourniquets, and that crowd control barriers were used as “makeshift stretchers,” it is hard to understand why there was not extensive evidence of blood on the footbridge, the steps, and the station concourse.

Crowd control barriers being used as “makeshift stretchers.” Source: Richplanet.net

Two Questionable Cases of Bleeding

There are only two publicly available examples, recorded on video, of casualties appearing to bleed, begging the question of why more such videos did not find their way onto social media.

Amy Barlow

One example is Amy Barlow, whom the BBC showed apparently bleeding through her trousers while sitting outside Manchester Victoria station.

Source: Manchester: The Night of the Bomb (15:13)

Hall (2020, p. 49) observes that Barlow can be seen, in three separate clips (00:34:00-00:36:00), “walking normally and briskly without any apparent injury” while exiting the Victoria Exchange Complex. It seems difficult to reconcile that with the apparently serious injury shown above.

Ruth Murrell

Ruth Murrell is captured in the Barr footage with what is obviously supposed to be a thigh wound bleeding through the right leg of her jeans:

Source of composite image: Hall (2020, p. 49)

Murrell here walks normally and is able to place her full weight on each foot. Her jeans do not appear to be torn by a projectile.

When the Queen visited Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital on May 25, 2017, Murrell told her, while pointing to her right thigh,

It was like nuts and bolts that everybody seems to be having […] and mine’s gone through 15 centimetres and out the other side, so I’m due in surgery later this afternoon.

Yet, she was not showing any obvious sign of injury or distress:

Source: ABC News

Recall Professor Anthony Bull’s description of blast fragments at the Inquiry:

Effectively, these cause anatomical deficit. They come into contact with the person and they disrupt the anatomy: they tear the anatomy, they push holes through the anatomy. This is like being hit by — being shot, but it’s typically worse than that because the fragments don’t only contain energy going in a straight line, they also contain rotational tumbling energy, which is a function of the shape of these fragments, and that tumbling energy causes more significant tearing of the anatomy that it comes into contact with. (pp. 25-26)

Clearly, Murrell’s observed gait in the Barr footage is inconsistent with the effects of a bomb blast as described by Professor Bull.

Davis (2024, p. 289) notes that

Soldiers in war zones with shrapnel injuries to their legs require medical assistance precisely because they cannot walk. Tourniquets are commonly applied to reduce the risk of arterial bleeding. Ruth Murrell had no such treatment provided to her either inside or outside the City Room.

Instead, Murrell walked across the footbridge and down the steps to to the Casualty Clearing Station (see Pighooey, 13:44). As we saw above, there is reason to suspect that she may have been responsible for the trail in front of the steps from the footbridge.

Once at the CCS, positioned in the war memorial entrance, Murrell can be seen in the image below, the “blood” from her original wound apparently drying out, but with the top part of her jeans, now including her upper left leg for some reason, also apparently damp. She appears to be applying pressure to an area that is higher than the original injury, and no blood has soaked through the white compress.

Source: The Irish Sun (snippet)

In sum, the source of the discolouration on Murrell’s jeans is unclear. We can infer, however, that Murrell did not sustain the injuries attributed to her by ITV News:

Source: Hall (2020, p. 49)

Moulage

As we have seen, irrefutable evidence of active bleeding in the Manchester Arena incident is unexpectedly difficult to track down, despite a TATP shrapnel bomb having officially gone off in a room full of hundreds of people.

Meanwhile, the only two pieces of video evidence appearing to show casualties bleeding (Barlow and Murrell) are beset with doubts about their authenticity.

As for the supposed “blood trails” captured on CCTV, it is important to remember Hall’s contention that “None of this is evidence of a genuine casualty or evidence of genuine blood” (46:50). We cannot tell from grainy CCTV images what exactly it is that we are looking at.

Hall told the High Court of Justice

I believe a number of members of the public, as many as a hundred or more, were recruited to take part in the mock terrorist attack, and part of their role was to report to the media and the public their experience of the incident. This involved some of the participants on the night exhibiting fake injuries using fake blood and other fake injury kits [§5.0]

The technical term for fake injury kits is moulage. Its application has become increasingly widespread since the rise of the crisis simulation industry in the last decade and a half.

We saw in Part 10 that mock terrorist exercises had been taking place in the years leading up to May 22, 2017, most notably Exercise Winchester Accord in May 2016, which involved hundreds of actors in moulage at the Trafford Centre, six miles away from the Arena.

Source: The Independent

But whereas the Trafford Centre simulation relied on volunteers, the real crisis simulation industry is a much more serious business.

To get a sense of the kinds of fake injuries that crisis simulation companies specialise in, readers with strong stomachs may wish to inspect the horrific facial injury kits used by the company Crisis Cast, or its use of amputee actors to create life-like simulations of soldiers with legs blown off in war zones. Discretion is strongly advised before viewing.

Simon Butler may have seen moulage when he witnessed one case where “at the time, the wounds weren’t actively bleeding, they were quite large and deep wounds, but they weren’t actively bleeding” (p. 136).

Brian Mitchell, the Lead Producer of Crisis Cast, stated the following in 2015:

Trained by behavioural psychologists, our specialist role-play actors — many with [national security] clearance — are rigorously rehearsed in criminal and victim behaviour. This level of expertise and accuracy is used to help police, government agencies, the military and the emergency services.

Thus, we are not just dealing with ordinary actors here, but, rather, psychologically trained specialists with national security clearance, working for the State. If such professionals were deployed during the Manchester Arena incident, they can be expected never to breathe a word about it.

Crisis Actors?

Despite the derision with which the public has been conditioned to treat claims of crisis actors being involved in “hoaxed” false flag terrorist events, only a fool would disregard all of the above evidence regarding the difficulty in tracking down real injuries/blood, plus possible fakery of injuries.

That is without getting into the Bickerstaff video, which demonstrates foreknowledge of the event and, thus, implies that Nick Bickerstaff was acting (see Part 2; Davis, 2024, pp. 196-204).

With such evidence in mind, let us look again at the Parker photograph.

I remarked in Part 14 that the Parker photograph shows mostly grown men, and none of the young females who predominantly made up the concert audience and the bulk of the named fatalities. Below is a close-up of three “casualties” in the foreground of the picture. The one closest and the one in the top right are obviously men, although it is harder to tell for the one on the left.

In theory, the casualty on the left, tended to by Michael Buckley, should be Kelly Brewster (see Part 14). If I have identified Brewster correctly on CCTV at 22:30:59 (see Part 14), then we cannot see her footwear:

We can, however, see that she is wearing a light cardigan that does not appear to be present on the person being tended to by Michael Buckley. She also appears to be wearing conventionally feminine clothing, whereas the person in the Parker photograph appears to be wearing trainers and jogging bottoms.

It is possible that I have misidentified Brewster, but it is equally possible that we are looking at three men lying on the floor. Who are they?

The only adult male fatalities were John Atkinson, Philip Tron, Marcin Klis, and Martyn Hett. Martin Hibbert claims to have been seriously injured. Other than that, I am not aware of any named adult males whom we should expect to find on the floor 12-15 minutes post-detonation.

Atkinson should be out of sight of the Parker photograph, near the pillar in the front of the box office (see Part 14). Klis should be next to his wife, Angelika. Hibbert should be next to his daughter, Eve. Tron should be next to Courtney Boyle. There does appear to be a woman in a pink top in front of the man in the top right, but she appears to be looking at her phone rather than lying fatally injured.

Hett was too slenderly built to be either of the two obvious men in the Parker photograph. So, again, who are the men on the floor?

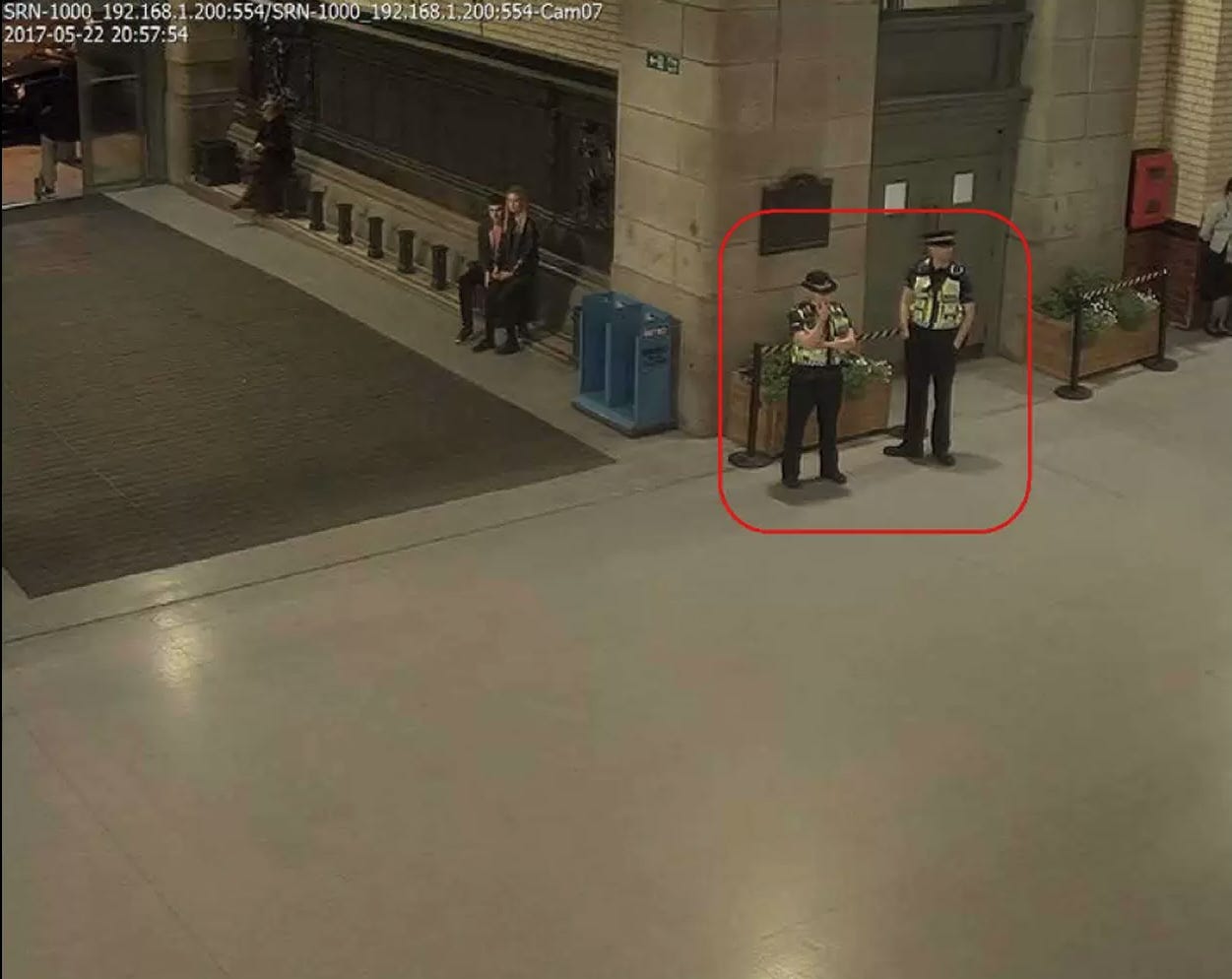

And, for that matter, who is the man front and centre of the Parker photograph in the Showsec uniform?

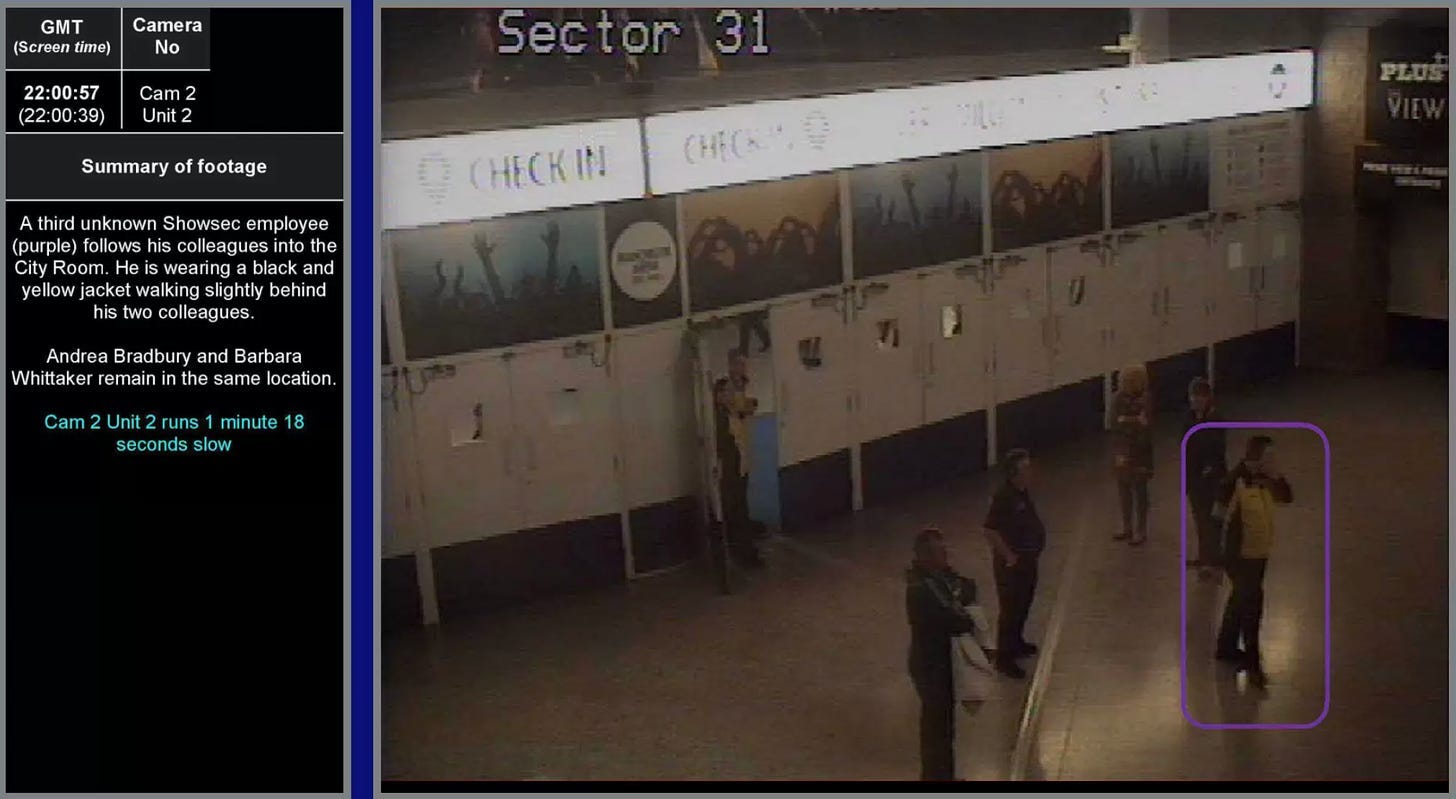

To this day, as far as I know, he has not been identified by anyone. For example, he is first seen on CCTV at 22:00:57, next to Andrea Bradbury and Dave Middleton (cf. Part 11), yet his identity is given as “unknown.” He appears on two more CCTV images at 22:02, again marked as “unknown.” Why did Operation Manteline not instruct Showsec to disclose his identity? Was he an operative?

Source:Richplanet.net

One of the many oddities about the Parker photograph is how few people in it are readily identifiable. Over the course of this series, we have encountered an enormous cast of characters, yet I can only identify two of them in the photograph, namely, Michael Buckley and Darron Coster.

I cannot see any of the named fatalities, or anyone who was taken to the Casualty Clearing station. Probably some of the BTP/ETUK/Showsec/Northern Rail staff would be identifiable with a bit of work, but in general the version of events codified in the Inquiry report simply does not match what appears in the photograph (or the Barr footage).

For example, who is the man on the left below? Is it Gareth Chapman (the man on the right)? It is hard to tell.

Who is the woman below, who appears to be tending to her lower left leg with her knee bent?

Returning to the thorny question of where the “blood” came from — particularly through clothing, rather than witnessed active bleeds — we have to take into account the extraordinary image discovered by Pighooey (01:35:35) on Getty Images, for which I have bought the permission rights (anyone wishing to help me with the cost of this can do so here.)

In it, a woman is seen carrying an object which is apparently connected by a wire/tube to her left lower leg area.

What is she holding? If it is a mobile phone, then what is the wire/tether/tube leading from it to her left calf? Could it be something like this, which then presumably would be leading down to the floor rather than her left calf? If so, was she working for the media, and is that how she gained access?

An alternative hypothesis is that this is some kind of fake injury kit, however, it would make no sense for the woman still to be wearing it if that were the case.

The photograph was taken by a long-lens photographer (Christopher Furlong) when fire and rescue officers were finally at the scene (top right), meaning that it is some time after 00:36 (p. 552).

Why were three apparently uninjured women in civilian clothing nonchalantly strolling through a cordoned-off area in the small hours of the morning? Who are they?

The full image, for reference

A Possible Preparation Zone

Recall Hall’s observation that the purple area below was inexplicably redacted on CCTV imagery after the bang (see Part 6):

Snippet from Hall, Manchester on Trial (1:02:25), plus my annotation in green

We know that Jane Tweddle and Gemma O’Donnell both officially collapsed in the area leading to the steps:

Joanne assisted Jane across the City Room as they went towards the City Room exit leading to Trinity Way. Jane reached the exit and collapsed on the ground just before the steps. (p. 29)

At 22.31.19, Gemma [O’Donnell, lifelong friend of John Atkinson] is seen to collapse on the floor, just around the corner from John and the stairs that lead down into the car park. (p. 7)

However, there is no obvious reason to redact the area in front of the lift. So, why redact it?

When Detective Chief Inspector Sam Pickering, Operation Manteline’s second in command, talked through this schematic with the Inquiry, the ringed area below was not mentioned (25:44).

Source: Inquiry report, Volume 3, p.132.

The last unredacted CCTV image of that area was captured at 22:09:50:

Source: Richplanet.net

The summary of footage here, indicates that Showsec’s Jordan Beak “heads toward the Disabled access ramp.” That ramp descends in three sections to the car park. The top part of the ramp is barely visible from the car park, and in theory it would not be difficult to park one or two vans that would completely block the view of the disabled access ramp area from the car park.

That area could, thus, in theory have been used as a preparation site if indeed any moulage were involved. Or, alternatively, any potential crisis actors could have down in the lift from the floors above. Either way, the redactions to the area in front of the lift would ensure that no one is seen emerging from that area.

Conclusion

Although the legacy media sought to persuade the public that the City Room was the scene of a bloodbath, evidence of blood in relation to the alleged mass casualty event of May 22, 2017, is remarkably hard to come by.

There is no evidence of blood pooling in the Barr footage or the Parker photograph, shot 12-15 minutes post-detonation (see Part 14).

Only 11 named victims in the 1,346-page Inquiry report can be found bleeding.

John Atkinson officially died from blood loss from his leg injuries (§18.156). However, close examination of the Inquiry transcripts proves surprisingly ambiguous when it comes to the source and extent of Atkinson’s bleeding.

Locating the source of casualties’ alleged blood loss proves unexpectedly challenging. The blood seems either to have been coming through clothing, or the blood loss was internal, and there appear to be few, if any, eyewitness accounts of active bleeding from visible wounds before casualties left for hospital.

Salman Abedi’s severed torso, falsely reported to have been hurled through the air by the legacy media, did not leave any visible blood spatter in CCTV or camera phone imagery — or indeed a torso.

The marks on the City Room floor, visible in the Barr footage and Parker photograph, are demonstrably not blood.

The potential blood trails visible on post-detonation CCTV imagery of the footbridge, the steps down to the station concourse, and the station concourse itself, are too faint and too few to account for the reported levels of bleeding following a TATP shrapnel bomb allegedly detonating in a room full of hundreds of people. Furthermore, it is far from clear that they are blood in the first place.

The only two cases of alleged bleeding caught on camera — Amy Barlow and Ruth Murrell — are both questionable, based on the evidence.

Therefore, we must take seriously Hall’s contention that moulage was involved, as it was in Exercise Winchester Accord, only this time involving trained crisis actors vetted by, and acting on behalf of, the State. After all, who exactly are most of the people seen in the Barr footage and Parker photograph? And where are all the named casualties and fatalities?

In the final analysis, while we should not be surprised by the coordinated deception on the part of the legacy media, it is, nevertheless, shocking that evidence of fakery is easier to find than irrefutable evidence of catastrophic blood loss. In that context, claims about crisis actors cannot readily be dismissed.