Part 17 - “Survivors”

Introduction

The last three parts of this series addressed the issues of fatalities, injuries, and blood. It has been shown that there is little, if any, primary empirical evidence available in the public domain which corroborates the official version of events. This is regardless of how powerful the “narrative” may be in terms of emotiveness, interlocking witness testimonies, legal authority, and promotion by the legacy media.

This Part and the next take as their theme the “survivors” of the Manchester Arena incident. This Part deals with some general considerations regarding the “survivors,” and Part 18 will examine individual “survivor” testimonies.

I place “survivors” in inverted commas, because it is far from clear, based on the preceding analysis, what, if anything, was survived. For example, there is no credible primary empirical evidence that a TATP shrapnel bomb went off in a crowded room full of hundreds of people (see Parts 2 and 15).

Here, I begin by considering why so few “survivors,” relative to their total number, were invited to give evidence at the Inquiry. What explains why some were chosen to give evidence but not others? Is it just a coincidence that six of the 13 “survivors” who gave evidence at the Inquiry regarding the post-detonation period also have their own pages on the Hudgell Solicitors website?

Injury details at the Inquiry were provided in relation to at least seven “survivors,” namely, Lisa Roussos, Martin and Eve Hibbert, Lucy Jarvis, Bradley Hurley, Hollie Booth, and Catherine Burke. Other “survivors” chose not to discuss their injuries. I place their testimonies in a broader perspective below.

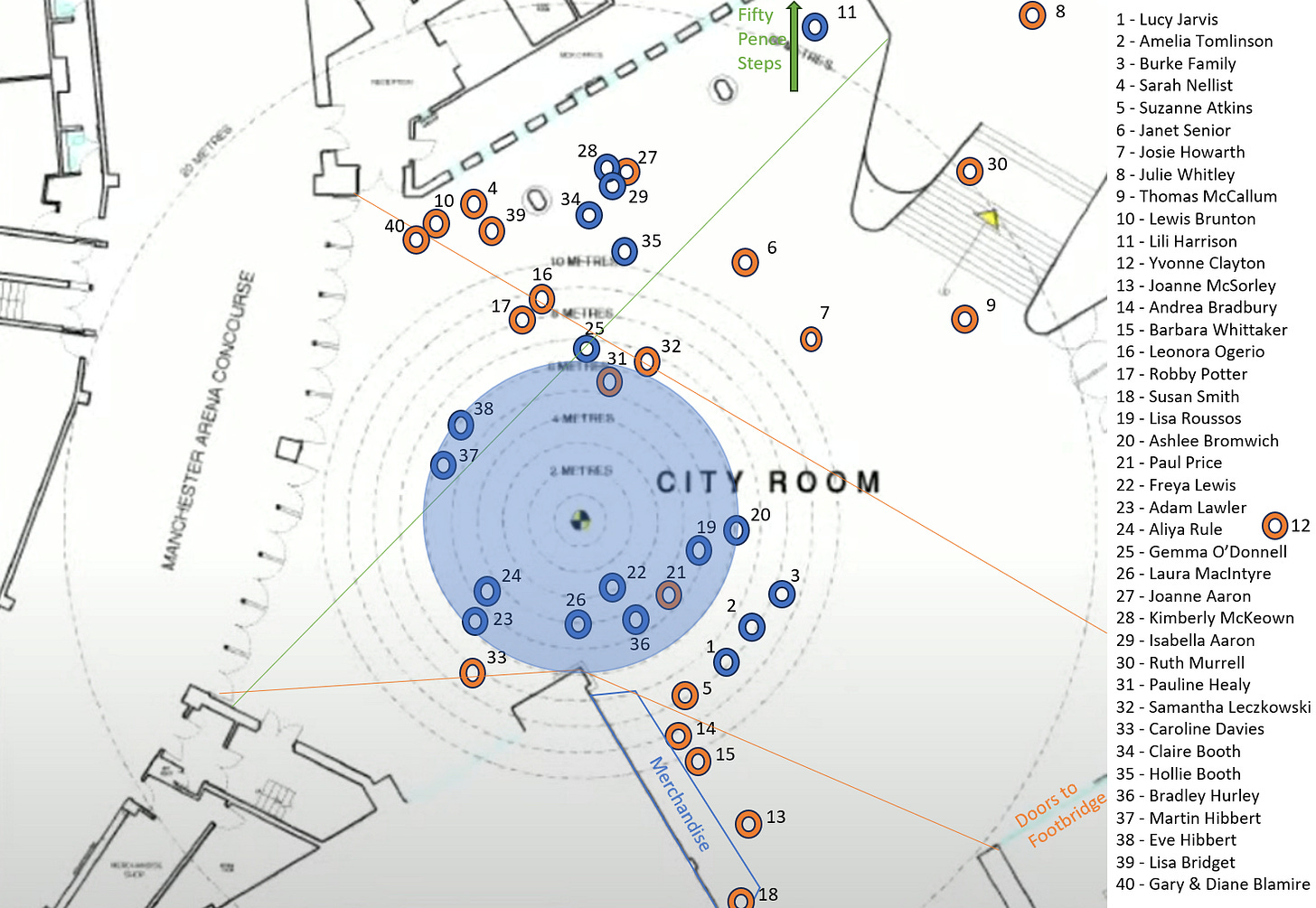

Who were the other “survivors,” and where were they located at the moment of detonation? Again, this is basic information that the public might reasonably expect the £31.6 million Inquiry to have provided. Yet, as with the 22 named fatalities, no attempt was made to show who was where when Abedi’s device went off. I have sought to pull that information together myself, based almost exclusively on information provided by the Inquiry. I also consider its implications.

Which “survivors” were definitely present in the City Room at the moment of detonation? Of the 40+ named “survivors” who I have managed to map, it is reasonable to expect that most should be readily identifiable on CCTV, which covered most of the area of the City Room, including the main entry point, i.e. the doors from the footbridge to the train station. Astonishingly, the opposite turns out to be true.

Finally, I consider the “survivors’” propaganda function. Even though it proves remarkably difficult to find primary empirical evidence that most of them were even in the City Room, their media influence has been disproportionately large. This began with the Queen’s visit to Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital on May 25, 2017, was exacerbated through two ITV and BBC documentaries, and continued through “survivor” appearances in various high-profile public spectacles and interviews.

Why Were So Few “Survivors” Invited To Give Evidence At The Inquiry?

Part 17 of the Inquiry report is titled “Those Who Survived,” and it claims to “describe the experience of some of those who were present in the City Room in the aftermath of the explosion and their recollection of the moment the bomb detonated” (§17.14).

“Before the attack,” it includes Josephine Howarth, Sarah Gullick, Janet Capper, and David Robson in three short paragraphs (§17.20-17.22).

“After the attack,” it includes Amelia Tomlinson and Lucy Jarvis (§17.24-17.28), Andrea Bradbury (§17.29-17.34), Darah Burke (§17.35-17.43), Janet Senior and Josephine Howarth (§17.44-17.52), Martin Hibbert (§17.53-17.61), Sarah Nellist (§17.62-17.63), and Suzanne Atkins (§17.64-17.68).

There is also a third category, i.e., “Those who were present in the City Room and survived the explosion but whose loved ones died in the Attack” (§17.17). This includes Paul Price, Claire Booth, Bradley Hurley, Lisa Roussos, and Andrew Roussos (who, however, was not present in the City Room at the moment of detonation) (§17.69-17.119).

Thus, the Inquiry report pays attention to a maximum of 16 “survivors” who were present in the City Room at 22:31:00 on May 22, 2017 (not double-counting Howarth and excluding Andrew Roussos). Hollie Booth and Eve Hibbert are covered in their parents’ accounts, taking the total to 18.

Three of the named “survivors” (Gullick, Capper, and Robson) are not cited in the post-detonation context, therefore, in terms of establishing what happened, “survivor” testimony is limited to just 13 accounts.

Remember, 59 casualties were taken to hospital in the early hours of May 23, 2017 (see Part 15), and 56 “survivors” later applied (unsuccessfully) for Core Participant status at the Inquiry (see Part 13). Therefore, less than a quarter of “survivors” appear in the Inquiry report, even though any of them, in theory, could have died.

Given that the stated purpose of the Inquiry was to “investigate how, and in what circumstances, 22 people came to lose their lives in the attack at the Manchester Arena on 22 May 2017,” one might have expected “those who survived” to have featured prominently.

Instead, consistent with the Inquiry’s general reticence to examine first-hand evidence relating to the post-detonation period transparently, there was a peculiar reluctance to hear from “survivors.” Considering how much time was spent confirming other mundane details (such as whether certain witnesses’ training records were up to date), the failure to hear more substantively from “survivors” about what happened seems suspicious.

Why Were Some “Survivors” Invited To Give Evidence But Not Others?

Short excerpts from the witness statements of at least ten “survivors” were read out at the Inquiry hearings, yet those “survivors” were not called to appear before the Inquiry in person. They were Jean Forster, Caroline Berry, Susan Smith, Joanne McSorley, Gary Blamire, Lauren Thorpe (regarding her eight-year-old daughter Lili Harrison), Robby Potter, his partner Leonora Ogerio, Lewis Brunton, and Yvonne Clayton (pp. 12-20, 44, 50). Why were they not called to give evidence?

Quoting Paul Greaney QC on Day 1 of the Inquiry, “survivors” were officially called to give evidence

where their experiences provide information, evidence or assistance to understand either the experiences of those who died or to ensure that lessons are properly learned, as is also a function of this inquiry. (p. 65)

For example, Martin Hibbert qualified by this logic, because he gave evidence regarding Eve being inappropriately covered, implying a lesson to be learned.

Yet, it is not entirely clear that all “survivors” who did appear before the Inquiry met Greaney’s criteria. For example, apart from Hibbert, it is unclear what any of the other “survivors” in the “After the attack” category contributed in terms of aiding the public’s understanding of the experiences of those who died or lessons to be learned.

In addition to Martin Hibbert, Greaney cited Andrea Bradbury, Gary Blamire, Emily Murrell, Lili Harrison, and Linda Carter as cases illustrative of where lessons could be learned (pp. 73-74).

However, of those six, only Hibbert and Bradbury were called to give evidence. Although Murrell and Harrison were minors, their parents who were with them on the night (Ruth Murrell, Lauren Thorpe, and Adam Harrison) did not appear before the Inquiry.

Therefore, there does not appear to be any obvious rhyme or reason why some “survivors” were called to give evidence but others were not.

This raises the possibility that ulterior motives may have been involved. For example, are we looking here at a cadre selected to portray a particular version of events to the public? This possibility cannot be discounted for reasons that will become increasingly clear over the course of this Part and the next.

Ruth Murrell mentioned in 2020 that “victims” were not supposed to give interviews without the approval of the GMP Family Liaison Officer, who was DCI Teresa Lam (see Part 12). Ostensibly, this was to avoid potentially upsetting other affected families, but clearly it reveals a form of narrative control by GMP.

It follows that if there is a cadre of “survivors” soaking up most of the public’s attention, then controlling the narrative around injuries and “survivors” becomes much easier.

The Role of Hudgell Solicitors

Over 150 “survivors” were represented by Hudgell Solicitors in their quest for “terrorism compensation.” As Hudgell’s Manager Terry Wilcox puts it,

Each and every person at the arena that night who suffered either physical or psychological injuries as a result of the bombing, or lost a loved one, deserves compensation for what happened.

No doubt Hudgell’s deserves its fees for helping them.

At least seven named “survivors” feature prominently on the Hudgell’s website. For example, below are Ruth Murrell, Sarah Nellist, Josephine Howarth and Janet Senior:

Source: Hudgell Solicitors

There are also individual pages for Martin Hibbert, Paul Price, and Andrea Bradbury. Given that the Inquiry report only names 13 “survivors” in a post-detonation context, it is conspicuous that six of them should also have their own pages on the Hudgell’s website.

Ruth Murrell has her own Hudgell’s page but was not called to give evidence at the Inquiry. She may have been deemed too risky for reasons given in Part 18.

Although interviews with countless “survivors” can be found in the legacy media, it seems that certain key individuals were chosen to play a central PR role. The Hudgell’s website also reflects this.

“Survivor” Injuries

Detailed injury accounts are provided in relation to at least seven “survivors” in the Inquiry report and transcripts. As with the three eventual fatalities who were evacuated from the City Room, those accounts contain some harrowing claims, and reader discretion is once again advised.

Although the legacy media contains other, similarly distressing accounts, it is a weak evidence source compared to sworn testimonies and will therefore be disregarded.

Lisa Roussos

According to the Inquiry report. “Lisa was so badly injured that she was put into an induced coma” (§17.118), in which she stayed for about two and a half weeks, undergoing a number of operations during that time as a result of the injuries she sustained (§17.110).

Her injuries were summarised as following by her lawyers:

Multiple projectile injuries to the limbs and body. Massive damage to the main artery at the back of the left knee, which required reconstructive surgery. Injury to right arm, including substantial complex fractures to the right forearm. A through and through injury to the palm of the right hand with bone loss. Fractures to both thigh bones. Fracture to cervical spine caused by foreign body. Penetrating injury to the right side of the chest caused by foreign body. Multiple additional soft tissue injuries to the trunk and limbs. A wound to right cheek. A ruptured membrane to the left ear. (pp. 155-156)

Martin and Eve Hibbert

Martin Hibbert was officially 5-6 metres from the seat of blast (§17.54) and suffered 22 shrapnel wounds, including one to the centre of his back which severed his spinal cord, leaving him paralysed from the waist down and with post-traumatic stress disorder (§17.61). Further details of his injuries, as he described them at the Inquiry, can be found in Part 7.

His daughter, Eve Hibbert, who was next to him, “was in hospital for ten months. Initially, her family were told that Eve would probably remain in a vegetative state, but she can now eat, talk and walk unassisted” (§17.61). Gory details of Eve’s head injury were put into the public domain by her father (see Part 7).

Lucy Jarvis

According to the Inquiry report, Lucy Jarvis underwent a 14-hour operation and was in hospital for eight weeks (§17.28). She concluded her evidence at the Inquiry by reading out a long list of her injuries:

I had multiple shrapnel wounds on the upper and lower legs. I had to have fasciotomies on my right leg on both sides to stop swelling. I had an injury to the common femoral vein and vascular system in my upper right thigh, which meant I almost lost my right leg. I had life−changing shrapnel wounds, shrapnel lodged deep in my left ankle in my talus bone, which required removal and bone grafts, and I had a fixator on my ankle for 10 months. I had a partially severed right big toe, which required fusing. I had multiple shrapnel injuries on both feet, including my metatarsal on my left foot, which — I now have like a gap where there’s a missing metatarsal bone. I had injuries to my left upper arm and forearm and my thumb. I had injuries on my left upper side of my torso, which went straight through my bladder into my right bum cheek. I had a damaged lower kidney, bowel and — sorry, severed urethra tube, which had to be reshaped and repaired. I had several shrapnel injuries to the bladder, which also had to be reshaped, and I had blood clots on my lungs due to the blast. (pp. 67-68)

Bradley Hurley

According to the Inquiry report, Bradley Hurley “knew straightaway that his legs were broken” (§17.88), and as he looked at his 15-year-old sister Megan, whom he knew had died, he “could not move and was bleeding heavily” (§17.91).

Sophie Cartwright QC read out a list of injuries sustained by Bradley Hurley, including: two broken legs; multiple entry shrapnel wounds presenting as wide holes in both legs, his feet, his left hand, and the left side of his jaw; second degree burns to his face and left arm; and a perforated left ear drum that has caused irreparable damage and will worsen with age (03:32:00).

According to Cartwright, apparently reading Hurley’s own evidence back to him, he spent over a month in hospital, two weeks of which were in the high dependency unit. He underwent four major operations on his legs and burns, and had to wear large external fixators on both legs for six months. Following two years of physiotherapy, his body had suffered irreparable damage and he remained in chronic back and leg pain.

Hollie Booth

The Inquiry heard that Hollie Booth, then 12 years old, was

very severely injured, [having] received around 13 shrapnel injuries or shrapnel wounds. She had a broken tibia and fibula in her left leg and a very badly broken left foot. […] The main nerve that travels down the left side of her body was damaged behind the knee, which meant she had no movement or feeling in her left leg and had a foot drop. Her right knee was very badly injured and she sustained damage to her bowels, which resulted in her requiring a colostomy. […] Hollie was an inpatient for 8 weeks initially, including time in the high dependency unit. […] She lost so much blood while she waited for help that she required a blood transfusion. […] She has so far required 17 operations. […] And has a number of operations left to come in the next few months. […] She was unable to walk unaided and wore a splint on her left leg for 2 years. […] Hollie’s knee has been reconstructed with a transplant bone from a donor […] She’s had a fusion to her left leg, although it was not directly injured in the bombing, and has ongoing problems with her bladder. (pp. 127-128)

Catherine Burke

Catherine Burke’s injuries were summarised at the Inquiry by her father, Darah Burke:

Catherine had […] multiple fractures of the right fibula, [plus] 15 other shrapnel wounds, including three on her lower leg, one on her right thigh, another one on her — well, two more on her right thigh. She also had a shrapnel wound to her right lower back and a soft tissue injury to her upper left back and two entrance and exit shrapnel wounds on her right forearm, causing significant muscle loss and two on her right bicep. She had a chest contusion and an open shrapnel wound on her chest and a linear abrasion, which was the bleeding to the right side of her head, and a laceration to her right ear as well, so that was in my opinion probably caused by shrapnel. That would have almost certainly led to complete permanent deafness affecting her right ear (pp. 72-73).

Despite the extent of his daughter’s injuries, Darah Burke GP sought to assist other casualties and accepted a P3 (“walking wounded”) classification for Catherine (who could not walk), until she was eventually upgraded to P2 (p. 78).

Analysis

As difficult as these reports are to read, it is important to provide some context.

For example, the Inquiry appears to have accepted uncritically any and all injury claims made. Not once, to my knowledge, was a witness challenged to provide proof of their injuries, nor am I aware of any statement made by the Chairman or his Counsel to the effect that all injury details had been checked and ratified against medical records by the Inquiry legal team or other competent authority.

On the contrary, the Inquiry was actively disinterested in medical evidence from Day 1, when Paul Greaney QC told Saunders that he was not being asked by “survivors” to consider any issue relating to their medical treatment (p. 65). This set the tone. First-hand medical evidence did not feature during the Inquiry, only second-hand reports from those claiming to have seen such evidence. As a result, the public has no way of independently assessing claims made about injuries.

Instead, the public is presented with a narrative about injuries and told by propagandists that questioning the narrative is shameful.

When Sophie Cartwright QC noted that Robert Potter, in his statement, “gives a large amount of detail about the medical treatment he received on the night at hospital,” Saunders replied “We don’t need to hear that. It’s really just how has he been affected in his daily life now” (p. 13). Cartwright then cited Potter’s claim that he had been “disabled for life,” and Potter’s word was good enough for Saunders.

Unless I have, in good faith, missed something important, the witnesses could have said anything about their injuries, and it would have entered the official record as fact simply because it was said under oath.

This in turn raises questions about the nature of the oaths taken. My understanding is that it is possible to commit perjury at a public inquiry. However, given that we seem to be dealing with an intelligence operation (see Part 10), are there national security provisions for being “allowed” to lie under oath without fear of punishment? And, if there are, are those provisions public knowledge?

Lest such questions seem preposterous, keep in mind that the UK Covert Human Intelligence (Criminal Conduct) Act (2021) gives 14 government agencies the mandate to commit crimes with impunity under certain circumstances. Thus, legalised criminality already exists in the UK.

We know that Martin Hibbert, whose evidence accounts for two of the seven cases above, was an unreliable witness (see Part 7). Therefore, we should be open to the possibility that some, or all, of the other five accounts above may also have been unreliable.

Even if we assume that all seven accounts are genuine — i.e., not only are the injuries real, but they were sustained as a direct result of Salman Abedi detonating a TATP shrapnel bomb in the City Room on May 22, 2017 — then they are too few in number to offer a statistically significant cross-section. For example, if at least 59 casualties were taken to hospital (excluding those who were privately transported), then at least 52 samples would need to be taken to achieve the standardly accepted 95% confidence level. Even dropping the confidence level to 90% still requires 49 samples. Seven cases cannot be regarded as representative of the full cohort of “survivors.”

Of the 38 casualties taken to the Casualty Clearing Station, 21 were labelled as P1, i.e. requiring immediate life-saving interventions (§12.404), and Hollie Booth was later upgraded to P1 status. Bradley Hurley was triaged as P2. This means that there were 17 P1 casualties out of 22 from or about whom the Inquiry did not hear evidence. So, again, the official evidence base in relation to P1 casualties is far too small to be statistically significant.

The only detailed descriptions of injuries in the official record relate to the seven “survivors” above, plus the three evacuated fatalities (Saffie-Rose Roussos, John Atkinson, Georgina Callander) — only ten cases in total. Given that we are dealing with an alleged mass casualty event involving 22 fatalities plus hundreds of self-reported “victims” (see Part 15), ten detailed injury descriptions constitutes a tiny sample size.

In the case of Lisa Roussos, Lucy Jarvis, and Bradley Hurley, the accounts of injuries given at the Inquiry were literally scripted, i.e. read out from a script. Perhaps this was necessary to ensure medical accuracy, but it does nothing to mitigate the impression that we are dealing here with a narrative, rather than empirically verifiable evidence.

Locating the “Survivors”

Diagrammatic Evidence

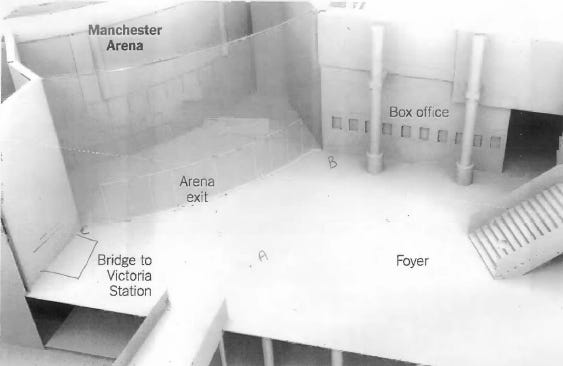

Strangely, given the difficulties in locating where in the City Room the 22 named fatalities fell (see Part 14), Operation Manteline asked some of the named “survivors” to plot their approximate location at the moment of detonation on diagrams of the City Room.

Lucy Jarvis and Amelia Tomlinson are marked by “LJ + AT” below. This information was provided by Tina Tomlinson, Amelia’s mother.

Source: National Archives

Darah Burke marked his family’s position as follows:

Source: National Archives

Sarah Nellist marked her position at the moment of detonation with the letter “B”:

Source: National Archives

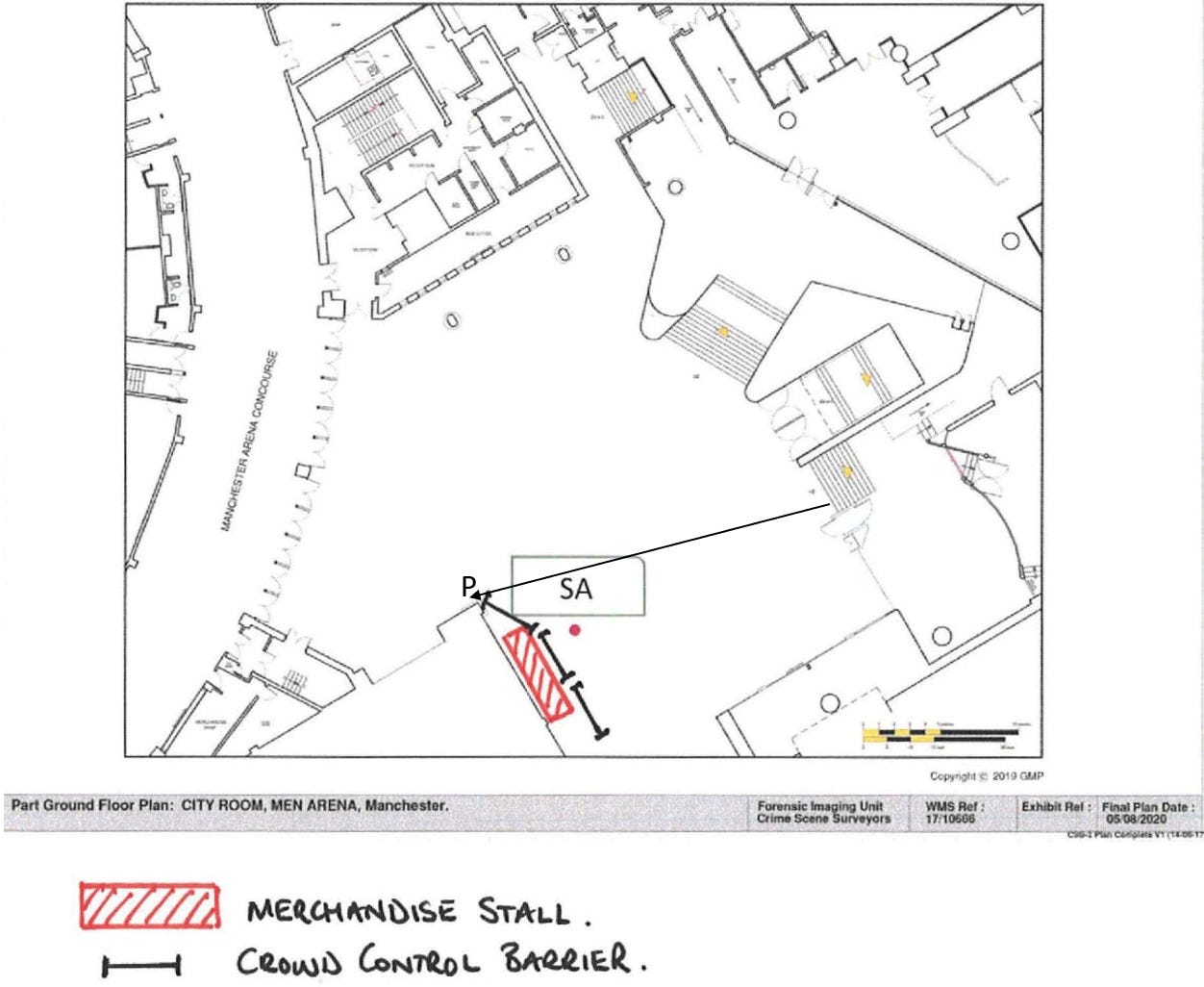

By 2020, when the Inquiry began, a proper scale map had been drawn up by “Crime Scene Surveyors” (see below).

Suzanne Atkins placed herself and her mother next to the merchandise stall as Salman Abedi (SA) allegedly passed them (p. 33), corroborating Davis’s contention that Abedi was headed towards “Point P” and not the official detonation site (see Part 2):

Source: National Archives, with my annotation of Abedi’s path and Point P

Janet Senior, who claims to have a photographic memory (p. 21), marked her position with an “x” below:

Source: National Archives

Her sister, Josie Howarth, who was with her, marked a different position, but which was nevertheless consistent with their described movement from the McDonald’s steps towards the box office (p. 20):

Source: National Archives

Witness Statement Evidence of “Survivor” Locations

In addition to the “survivors” who were asked to plot their positions on the diagrams above (all of whom were called to give evidence at the Inquiry), the witness statements of other “survivors” give clues regarding their locations at the moment of detonation. For example:

Lewis Brunton: “I moved towards the right corner, not too far from the box office on my right−hand side. I would say I was around 3 to 4 metres from the nearest exit door, which is in front of me” (p. 46).

Gary Blamire and his wife, Diane, “waited quite close to the box office” (p. 34). Gary was “blown off [his] feet on to the floor,” while Diane ended up “about 3 feet away from me […] in the doorway of the arena” (p. 35).

Lauren Thorpe (mother of Lili Harrison): “We came straight out into the box office area and headed left from the exit towards the stairs to take you down to the car park […] We were near the stairs when I heard it go off” (pp. 48-49).

Yvonne Clayton (partner of Andrew Scullion): “We got to the foyer having come through the doors linking the arena and Manchester Victoria and stood near to the steps at the back that were next to the doors leading to the station” (p. 53). Clayton also gave evidence corroborating the claim that Abedi deposited his rucksack at Point P: ”Having thought about the explosion since, I think it came from the far left near to where the T−shirt stand was” (p. 55).

Joanne McSorley was “near to the merchandise stall” with her mother, Susan Smith (p. 17). Smith was “leaning against a lip on the wall” (p. 42).

Andrea Bradbury and Barbara Whittaker claimed to have been “near to the merchandise stall” (§17.30).

According to Leonora Ogerio, “I was stood with my partner [Robert Potter], about two car lengths (approximately 9 metres) away from the doors into the arena, in the centre of the area […] I then felt an impact and was thrown and fell on my back” (p. 28).

According to Robert Potter, “When we initially returned to the arena foyer, we stood at the back by some steps. We were close to a pillar […] As time ticked on, we moved a little further forward and were now more towards the middle of the foyer […] When the bomb went off, Leonora was standing to my right and I had my right arm around her (p. 8).

Christopher Wild and his partner, Julie Whitley, can be seen on CCTV on the mezzanine to the front right of the doors to the JD Williams store. Whitley was injured: Wild drove her to hospital (along with his daughter and her friend), where she remained for 11 days (p. 51).

Lisa Bridget claimed to have been standing “approximately 20 feet (6.1 metres) from the main concert doors towards the right side near to the box office.”

Thomas McCallum, who is seen in front of the Grey Doors on CCTV, claimed to have been “significantly injured” and was assisted out of the City Room in a wheelchair (pp. 9-10).

Those Accompanying the 22 Named Fatalities

It is reasonable to expect that those standing next to the 22 named fatalities at the moment of detonation would also have suffered serious injuries. Here is what we find:

Samantha Leczkowski and Pauline Healy were Sorrell Leczkowski’s mother and grandmother, respectively (p. 71). There is no mention of injuries to Samantha Leczkowski in the transcripts or the Inquiry report, but at the Hashem Abedi trial she reportedly stated “I don’t care that my leg doesn’t work — the pain in my heart [from the loss of Sorrell] is the worst pain that won’t go away.” Pauline Healy was taken to the CCS as a P2 casualty.

Caroline Davies was with Wendy Fawell (pp. 17-18). The two were standing “apart from each other in order not to miss their children”; there is no official mention of what happened to Davies, but the legacy media claims she was “injured in the blast.”

Bradley Hurley was with his sister Megan and was taken to the Casualty Clearing Station as a P2 casualty (§17.87, §17.101).

Lisa Roussos and Ashlee Bromwich were the mother and sister of Saffie-Rose Roussos (p. 12). Lisa Roussos officially sustained major injuries (see above), yet Bromwich was able to walk to Hunts Bank close to Chetham’s School of Music; she was “stable, but injured and confused” (§17.113).

Paul Price (partner of Elaine McIver [pp. 45-46]) was “seriously injured by the explosion” (§17.70).

Freya Lewis was with her friend, Nell Jones (p. 25). The only mention of Lewis in the transcripts is that “She describes walking past a man with a backpack on at the same moment that she pressed send on a text message to her father” (p. 61). Legacy media reports state she was three metres away from the seat of blast and was seriously injured.

Adam Lawler was with Olivia Campbell-Hardy [p. 16]). Although it is noted that “they walked across the City Room together” (pp. 16-17), no official mention is made of what happened to Lawler. According to ITV’s Manchester: 100 Days After The Attack, “a bolt passed through his cheek, and another through his chin. He lost seven teeth” (27:55) and “Both of Adam’s legs were also fractured” (28:20).

Aliya Rule, who was with Georgina Callander (p. 14) is not mentioned in the Inquiry report and is only referred to as Callander’s “friend” in the transcripts (p. 6). The BBC claims she had “awful injuries to her leg.”

Claire and Hollie Booth, who were with Claire’s sister, Kelly Brewster (p. 4), were both taken to the CCS as P2 casualties; Hollie was later reclassified as P1. Claire Booth (and possibly Hollie) can be seen on CCTV at 22:30:59 (see Part 15).

Gemma O’Donnell was with John Atkinson (p. 7) and at 23:01 was assisted down the stairs to the Fifty Pence area by two police officers (p. 25).

Eilidh MacLeod was “walking just behind her friend. Eilidh was approximately 4 metres away from the bomber at the time of detonation” (p. 65). No official mention is made of what happened to the friend, Laura MacIntyre, but the legacy media reports “serious injuries to her hands and legs.”

Joanne Aaron, her daughter, Isabella Aaron, and her friend, Kim McKeown were with Jane Tweddle (p. 28). The transcripts state that “following the explosion, Joanne assisted Jane across the City Room,” crouched next to her at 22:33:27, assisted her at 22.34.49, put her arm in the air to summon help at 22:42:29, and encouraged her at 22:53:10 (p. 29). Officially, there is no indication that Joanne Aaron was injured, and no mention of what happened to the two girls.

Ruth Murrell (standing to the left of Michelle Kiss [p. 23]) walked to the CCS as a P2 casualty (see Part 16). Murrell’s daughter Emily was also taken to the CCS as a P2 and should have been a P1 (p. 74).

Martyn Hett, despite entering the Arena concourse with Lewis Conroy when the concert finished, was seen filming himself in the City Room shortly prior to the explosion and was not unmistakably next to any named person (pp. 8-9).

Alison Howe and Lisa Lees were together and with no one else (p. 4).

Liam Curry and Chloe Rutherford were together and with no one else (p. 99).

Marcin Klis and Angelika Klis were together and with no one else (p. 105).

Philip Tron and Courtney Boyle were together and with no one else (p. 8).

Thus, ignoring untrustworthy legacy media reports, the official account lists injuries to Pauline Healy, Bradley Hurley, Lisa Roussos, Ashlee Bromwich, Paul Price, Claire and Hollie Booth, Gemma O’Donnell, and Ruth and Emily Murrell. In all cases apart from Bromwich and O’Donnell, the injuries were P1 or P2, as we would expect.

The official documentation does not speak to the reported injuries of Samantha Leczkowski, Caroline Davies, Freya Lewis, Adam Lawler, and Aliya Rule, nor does it have anything to say about the condition of Laura MacIntyre, Joanne and Isabella Aaron, and Kimberly McKeown.

Plotting the “Survivors”

Putting all of this evidence together, we can plot the approximate locations of the above “survivors” as follows. The locations of those who were next to the 22 are based on the corresponding map in Part 14.

Approximate locations of 40+“survivors” at the moment of detonation. The map does not extend far enough to show Clayton’s [12] location towards the far corner of the City Room.

In addition to the 40+ survivors that I have plotted based on evidence from the Inquiry, Hall (2020, pp. 36-38) identifies the following 27 “injured victims,” presumably from media reports: Gabrielle Price, Charlotte Fawell, Natalie Senior, Emilia Senior, Adam Harrison, Lauren Thorpe, Millie Robson, Laura Anderson, Millie Mitchell, Evie Mills, Lisa Arnott, Jade Arnott, Andy Wholey, Ella McGovern, Hannah Mone, Yasmin Lee, Gary Walker, Maria Walker, Pietr Chylewska, Rob Hay, Julie Thomas, Lizzie and Olivia Murtagh, Acacia Coward, Paul Greenan (cf. p. 19), Adrian Thorpe, and Phil Hassall. Of these, Hall attributes the most serious reported injuries to Mitchell, Mills, McGovern, the Walkers, Chylewska, Thomas, Greenan, and Hassall.

As far as I can ascertain from searching the National Archives (using the search bar in the top right), none of these individuals features in the Inquiry’s records. I therefore do not propose to include them in my analysis, since media reports alone tell us nothing reliable. The most effective criticisms are of the official version of events as established by the Inquiry.

Analysis of the Distribution of “Survivors”

At one level, the spread of the “survivors” makes sense, given the dominant exit path between the orange lines. Those making their way out are marked in blue; those waiting appear in orange. Those in blue above the green line are known to have been making their way towards the Fifty Pence Steps.

However, there are some important inconsistencies. For example, 19 of the 22 fatalities were located within six metres of the seat of detonation (the blue circle; see Part 14), but so too were 11 “survivors.” Why, then, were those 11 not also killed?

Remember, we are dealing here with not only with the primary shock wave (which, Professor Anthony Bull told the Inquiry, tears flesh from bone), but also the impact of the shrapnel and the crushing impact of the tertiary blast wave, whose collective effects, as Colonel Peter Mahoney told the Inquiry, are in a “league of their own” compared to a “very mutilating road traffic accident” (p. 70). It is hard to see how anyone at close range could have survived this.

For that matter, why were many more people not killed or seriously injured as a result of a TATP shrapnel bomb detonating in the middle of the City Room (see Part 15)?

Why do the effects of the blast appear to be selectively distributed? For example, why was Jane Tweddle killed, yet there is no evidence in the Inquiry records that anyone in the group she was with was injured (see Part 15)?

Why was Michelle Kiss, officially, killed at the top of the JD Williams steps, yet Ruth Murrell, who was standing right next to her, was not? Why was Julie Whitley, standing in roughly the same location as Murrell and Kiss, hospitalised for 11 days, yet her partner, Christopher Wild, who was standing next to her, was fit to drive her and two children to hospital? How come Jean Forster and her partner, Dave Robson, who were also standing in the same approximate location, did not feel the blast and were unharmed?

The officially recorded injuries and fatalities are too sporadic to be consistent with concentric waves of damage caused by a bomb blast.

Which “Survivors” Were Definitely Present?

The Problematic Case of the Hibberts

One of the most disturbing things that came to light during the Richard D. Hall trial was the possibility that the claimants, Martin and Eve Hibbert, may not even have been present at the Manchester Arena on May 22, 2017.

As discussed in Parts 3 and 7, Hall could find no photographic, CCTV, or other evidence proving that the Hibberts attended the concert. Despite claiming to have had a box seat, they uploaded no photographs or videos of themselves to social media from inside the venue. They do not appear in anyone else’s photographs, nor can they be seen on publicly available CCTV imagery, or in the Barr footage, where one should expect to find them moving from the Arena concourse doors towards the camera.

The easiest way of settling that dispute, to Hall’s detriment, would have been for the High Court of Justice to order the release of the 20:03 CCTV image that officially includes Martin and Eve Hibbert entering the City Room. Hall’s request that this be done, however, was not met, suggesting that the image, in all likelihood, does not exist (see Part 3).

Hall also requested to see medical evidence that Martin Hibbert sustained his injuries on the night of the concert. This, too, was not forthcoming (Part 3).

Thus, following a three-year public inquiry and a high profile case in the High Court of Justice, the public has still not seen any positive proof that the Hibberts attended the concert. This is highly suspicious.

Lack of CCTV Evidence for Most “Survivors”

If there is good reason to doubt that the Hibberts were present at the Arena on the night, what about the other “survivors”? Davis (2024, p. 291) notes that

Among the most seriously injured survivors were said to be Eve Senior, Bradley Hurley, Paul Price, Lisa Roussos, Eve Hibbert, and Martin Hibbert. None of them are seen in any CCTV images and none of them can be placed within the City Room.

Eve Senior can at least be seen outside the Arena afterwards in the iconic image that featured in news reports everywhere, even if her injuries do not appear consistent with the large number of shrapnel wounds reported by the BBC.

However, the lack of publicly available CCTV, photographic, and other evidence placing other “survivors” in the City Room is a real problem. Claire and (I think) Hollie Booth can be seen at 22:30:59 (one second before the official detonation time). Ruth Murrell can be seen at 22:28:14. Andrea Bradbury and Barbara Whittaker can be seen at 22:28:01, but not immediately pre-detonation. Joanna and Isabella Aaron and Kimberly McKeown can be see at 22:30:59, but there is no official evidence that they were injured.

Josephine Howarth can be seen at 22:30:28, 22:30:32, and 22:30:41, and her sister, Janet Senior can be seen alongside her at 22:30:32 and 22:30:41 as they emerge from the bottom of the McDonald’s steps just ahead of Salman Abedi (p. 16).

Josephine Howarth and Barbara emerge from the McDonald’s steps just ahead of Salman Abedi and cross the City Room. Source: Richplanet.net. Snippets, with my annotations in white

Otherwise, it is not clear, from publicly available primary empirical evidence, that any of the other 40+ “survivors” named above was actually present in the City Room at the moment of detonation.

Why are only six of them (Booth, Murrell, Howarth, Senior, Bradbury and, to a lesser extent, Whittaker) given as injured in the official records and definitely identifiable on CCTV? And of those six, why is only Booth definitely visible at 22:30:59?

This seems more than a little odd, given the large area that was covered by CCTV pre-detonation (shown in vanilla below, with grey marking the CCTV blind spots).

Unless someone can demonstrate otherwise — and I would be glad to receive new evidence — we appear to be missing over 30 named “survivors” on CCTV. It stretches credulity to suggest that none of them were seen entering or crossing the City Room, or that they all took up locations in CCTV blind spots.

The lack of publicly available CCTV and other evidence confirming the presence of “survivors” in the City Room begs the question: how many named “survivors” were present in the City Room when Salman Abedi’s device went off?

“Survivors” And The Media

“Survivors” As Propaganda Instruments

Following the Strategy of Tension, the public in the “War on Terror” must not be allowed to forget about the ever-present threat of Islamist terrorism, which could strike anywhere, any time, against even the most innocent, such as teenage girls at a pop concert. Only then will it acquiesce to oppressive social control (“security”) measures deceptively sold as keeping it “safe.”

Even though so-called terrorism experts tell us that the psychological impact on the public is more important than taking lives in the eyes of terrorists, the legacy media plays the key role in getting messages of fear into the minds of the public. Which begs the question of who the terrorists really are.

Rather than being afforded the privacy to piece their lives back together following a major traumatic event, many “survivors” of the Manchester Arena incident were thrust into the media spotlight. Some, like Martin Hibbert, have remained there ever since. Regrettably, their propaganda function cannot be ignored.

The Queen’s Visit to Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital

A classic example of “survivors” being instrumentalised for propaganda purposes is the visit of Queen Elizabeth II to Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital on May 25, 2017. She met four named victims, all female: 15-year-old Millie Robson, 14-year-old Evie Mills, 12-year-old Amy Barlow, and Ruth Murrell (mother of 12-year-old Emily Murrell).

This high-profile event created the impression in the public mind of the deliberate targeting of young teenage girls by Islamist terrorism.

I noted Richard D. Hall’s evidence-based doubts about Amy Barlow and Ruth Murrell’s injuries in Part 16.

Despite the Mirror’s claim that Millie Robson had been “blown up by [a] terrorist” and was “left with savage injuries, including ‘holes’ in her legs where shrapnel burnt through her skin,” she did not appear overly distressed some 60 hours later:

Source: The Royal Family

Note the staged appearance of the scene: two soft toys shoved next to Millie (one with an Ariana Grande tag on), matching balloons probably bought from the same shop, no sign of cards or flowers, no medical records at the end of the bed, and an Ariana Grande T-shirt rather than a hospital gown. For some reason, her mother is not expected to stand in the presence of the Queen. The whole scene looks inauthentic and created for the cameras.

Manchester: 100 Days After The Attack

Two important propaganda programmes designed to etch the official narrative into public consciousness in the UK were ITV’s Manchester: 100 Days After The Attack (August 29, 2017) and the BBC’s Manchester: The Night of the Bomb (May 22, 2018). “Survivors” featured prominently in both.

The ITV programme features Martin Hibbert extensively, as well as two teenagers said to have been seriously injured, namely, Adam Lawler and Lucy Jarvis. There are additional appearances by HART paramedic Lea Vaughan, Travel Safe Officers Philip Clegg and Niall Pentony, Lucy Jarvis’ parents, Olivia Campbell-Hardy’s parents, and a friend of Eilidh MacLeod, among others. Eight-year-old Lily Harrison is reunited with PC Cath Daley (BTP), who officially saved her life by taking her to hospital in a police van; her mother, Lauren Thorpe, becomes tearful. Sentimental music plays through most of the programme, which is clearly designed to play on the emotions. The outpouring of public grief at Manchester St. Anne’s Square is also shown, and “survivors” are shown piecing their lives back together.

Manchester: The Night of the Bomb

The BBC programme, at the beginning and end, features teenage girls who attended the concert: Amelia Tomlinson, Acacia Seward, Ella McGovern, Emilia Senior, Eve Senior, Eve Crossley, Tegan Sinnott, and Ashley Ogerio. The purpose of this is to stoke public outrage at the evil terrorist attack on innocent young girls and thereby to encourage emotional investment in the official narrative.

A leitmotif is the girls brushing their lovely hair. This intentionally jars with Tomlinson’s stated desire to know whether the ear which she found in her hair belonged to Salman Abedi (56:00) and McGovern’s claim, supported by her mother, that when washing her hair afterwards, the plughole got “blocked with so much flesh” (56:20). This is truly vile propaganda, but interestingly, it echoes Abby Mullen’s claim in the Mail on May 23, 2017, that “I’m still finding bits of god knows what in my hair.” This suggests that the idea of teenage girls finding parts of human remains in their hair was pre-scripted.

Greater Manchester Police and Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service declined to take part in the programme. However, numerous British Transport Police staff are featured, including PC Jessica Bullough, PC Stephen Corke, Superintendent Kyle Gordon, PC Jane Bridgewater, PC Matthew Martin, PC Thomas Campbell, PC Dale Edwards, PC Dale Allcock, and CI Andrea Graham. Graham ludicrously claims to have identified Abedi as the perpetrator on the night based purely on CCTV imagery (56:03; cf. Davis, 2024, p. 246).

The BBC seeks to justify the lack of ambulance staff in the City Room by having Stephen Hynes (39:00) and Daniel Smith (40:15) of North West Ambulance Service (both Bronze Commanders on the night) talking about protocol that prohibits ambulance staff from working in a hot zone; it is for police to secure the area first. This attempted vindication of the emergency service response does not hold water, however, in view of the evidence presented in Part 9.

The programme’s treatment of injuries, which is without any sound evidential foundation, is discussed in Part 15.

With the help of Salman Abedi’s former head teacher, Ian Fenn, David Anderson QC, and two of Abedi’s former acquaintances, Abedi is painted as violently misogynistic, disrespectful of authority, and an ISIS sympathiser, while sinister music plays in the background. BTP Director of Intelligence DS Nick Sedgemore links Abedi to TATP, which was demonstrably not used (see Part 2).

Lord Anderson, as he now is, authored a 2017 report assessing MI5 and police internal reviews regarding four terrorist attacks in London and Manchester that year. However, he does not inspire confidence as an intelligence expert. For instance, he told the BBC that Abedi “detonated his suicide vest,” yet Abedi was not wearing a suicide vest.

There is footage relating to Eilidh MacLeod’s funeral (49:00). It is interesting that both ITV and the BBC chose to focus on this one funeral, perhaps because it was the first, but the BBC also used it to convey the message that no one is safe from terrorism, not even in the Outer Hebrides (where the funeral took place), thus turning it into an opportunity to spread “War on Terror” propaganda.

The BBC programme concludes with multiple reminders of the supposedly ever-present danger of terrorism. Neal Keeling, Chief Reporter for Manchester Evening News, claims “We are a target. That’s an uncomfortable truth we’ve got to live with.” Eve Senior states “these terrorists are everywhere.” Another of the young girls states “they think it’s okay to kill kids at concerts.” Superintendent Kyle Gordon claimed that his 21 years of policing in Northern Ireland did not prepare him for what happened in Manchester.

Such was the “War on Terror” propaganda which “survivors” were co-opted to promote.

“Survivors” in Public Spectacles

“Survivors,” mostly young and female, featured in high profile public spectacles, such as the Pride of Britain Awards (November 2017), where they met Prince William and Ed Sheeran, with numerous celebrities in the audience. The full clip can be seen here.

From left to right: Ed Sheeran, Catherine Burke, Ann Burke, Emilia Senior, Adam Lawler, [?], Eve Senior, Natalie Senior, Ruth Murrell, Hollie Booth, Lauren Thorpe, Lili Harrison, Prince William, and presenter Carol Vorderman. Source: BBC

Freya Lewis gave an emotional performance at the NHS Heroes Awards in May 2018.

Source: The Mirror

Hollie Booth featured on the prime time talent show, Britain’s Got Talent (April 2018).

Source: Daily Mail

Note the Manchester bee on the girls’ T-shirts, which was used as a propaganda symbol to manufacture solidarity around the official narrative. Like the “I love Manchester” slogan, it appeared everywhere after the incident, from social media profiles, to murals and graffiti, to merchandise and tattoos, to the Bee The Difference choir set up for “survivors” — almost certainly an exercise in “controlled spontaneity” by the Government. Arianna Grande’s tweet after the attack was, at one stage, the most retweeted message in the history of Twitter (53:10), something which does not happen by accident.

Some “survivors” were kept in the public eye by fundraising campaigns. For example, Gary Blamire and his wife Dianne helped publicise the rehabilitation programme for “survivors” that was funded by public donations. Freya Lewis took part in the 2022 Great Manchester Run to raise funds for Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital, which she credits with “saving her life,” and was honoured by Prince William for her efforts. Martin Hibbert scaled Mount Kilimanjaro to raise funds for the Spinal Injury Association in June 2022.

“Survivors” also became public faces for charitable organisations, e.g. Hibbert as Vice-President of the Spinal Injury Association, Leonora Ogerio as ambassador for the Scar Free Foundation, and Lucy Jarvis in her work with the National Emergencies Trust.

Hibbert alone had made 160 media appearances by mid-2023 (05:30), averaging one a fortnight for six years while also training for the 2018 Great Manchester Run, going to Australia for treatment in 2019, scaling Kilimanjaro in 2022, and instigating a legal case in the High Court of Justice which enhanced his visibility even further. He now ranks in the “Disability Power List top 10.” Evidently, he is no mere “survivor”; he is a powerful influencer of public perception and opinion.

According to Davis (2024, p. 287), Ruth Murrell gave “more interviews than most of the so-called ‘victims.’” For instance, she appeared on Pride of Britain in 2017, thanking emergency responders (02:20), and she featured in the first “Story” of the Manchester Emergency Fund’s first annual report (p. 17).

There are countless legacy media articles on other “survivors.” Such articles serve as a constant remember to the public of the danger of terrorism and, thus, of the implicit need to surrender civil liberties in exchange for “security.”

Conclusion

There is no good reason why the Inquiry should have been so reluctant to hear from “survivors.” Given that its stated purpose was to investigate the circumstances surrounding the deaths of the 22, “survivor” accounts should have been front and centre.

Instead, evidence from relatively few “survivors” was buried in Part 17 of the Inquiry report, right after evidence from the “Blast Wave Panel of Experts” that largely contradicts it.

There is no obvious rationale behind the choice of “survivors” called to give evidence at the Inquiry. Instead, it appears more likely that we are dealing with a cadre selected to act as the public face of the “injured” for purposes of narrative control.

Even though the injury details provided by some of those “survivors” are harrowing, the public has still not seen any primary empirical evidence proving that the injuries came about as a direct result of Salman Abedi detonating a TATP shrapnel bomb. The “Inquiry” simply took all injury claims as read and made no attempt to verify them. Seven testimonies of serious injuries is, in any case, too small an evidence base on which to establish that at least 59 casualties were taken to hospital and hundreds more people were injured.

The Inquiry failed to plot where the “survivors” were located at the moment of detonation. Doing so leaves many unanswered questions in terms of the scale and distribution of injuries.

As best I can ascertain, only six injured “survivors” can definitely be seen on CCTV pre-detonation, and only one of them is identifiable one second before the official detonation time. Where are all the others? There should be scores more.

Instead, the “survivors” are far more visible on television afterwards than they are in the primary empirical evidence. They met the Queen, appeared in high-profile “documentaries,” featured in awards shows and talent shows, engaged in fundraising activities, fronted for charities, and engaged in a steady stream of interviews. Since when has maintaining visibility been the natural response to experiencing a major traumatic event?

All in all, the “survivors” fit the logic that has become ever clearer since Part 14, i.e., they are part of a narrative that has remarkably little primary empirical evidence to substantiate it, at least not in the public domain.