Part 12 - Operation Manteline

Introduction

This is the twelfth article in a series on the Richard D. Hall case. Since Part 9, this series has been dealing, not with the Hall case itself, but, rather, with what the lawfare against Hall was intended to keep hidden.

The previous two parts of this series highlighted the central role played by the security services (most likely MI5) and Counter Terrorism in relation to the Manchester Arena incident. This includes the similarities between Exercise Winchester Accord and what took place on May 22, 2017, evidence that the City Room was turned into a controlled environment, anomalies regarding crime scene management, possible motives for a staged attack, and potential operatives.

One troubling aspect of Hall’s “staged attack” hypothesis is confirmatory evidence provided by Iain Davis and “Pighooey” that building damage was fabricated after the Barr footage was recorded at or around 22:35.

As discussed in Part 2, Davis demonstrates that damage to the hospitality suite doors, as presented by Operation Manteline (the criminal investigation into the alleged attack), is not present in the Barr footage.

Sources: Iain Davis and Manchester Arena Inquiry (03:06:02)

In case cognitive dissonance causes the four large black damage marks on the otherwise pristine white doors to disappear because of “pixelation,” then Pighooey’s evidence, presented in Part 10, leaves no doubt that certain building damage was fabricated overnight.

Pighooey demonstrates that the two black marks ringed in red below, which were visible the next morning, are not visible in the Barr footage.

Source: Pighooey

Furthermore, look closely at the evidence of “shrapnel damage” to the wall provided by Operation Manteline:

Source: Manchester Arena Inquiry (03:05:40)

The original Inquiry video can be watched below. Fast forward to the three hour mark.

All of the marks shown on the walls by Operation Manteline are very nearly identical in size and shape, in a right-angled "U" shape, rotated at different angles. Given the various items in the alleged shrapnel (nuts, bolts, cross-dowels), all of which would have impacted the wall in different ways, this is not what one would expect to see. It looks likes an amateurish photoshop effort. There are no photographs of the wall from a different angle to corroborate the damage (which would be very hard to fake from two different angles).

Compare the Operation Manteline photograph to a later photograph of the same section of wall. Clearly the brickwork was not replaced. Therefore, what happened to all the damage marks?

Sources: Manchester Arena Inquiry (03:05:40) and Wikimedia

Similarly, the Operation Manteline image below left, contrasted with the later image of the same section of wall, clearly indicates that the brickwork was not replaced. So again, where did all the pock marks go?

Sources: Manchester Arena Inquiry (03:05:55) and Wikimedia

The Operation Manteline imagery above was shown in a video played at the Inquiry but was not released separately. It may have been intended for the Inquiry legal team, rather than for wider public consumption.

In fact, the only evidence of building damage comes from Operation Manteline. Otherwise, as analysed in Part 2, there is no evidence of building damage whatsoever: no damage to glass doors, windows (including the giant skylight), lighting, walls, the floor, the merchandise stall and giant poster, the pillars in front the ticket office, etc.

Certainly, there is nothing in the primary empirical evidence to indicate that a TATP shrapnel bomb went off inside the City Room. However, as Davis (2024, p. 230) writes, we can deduce that someone had been tasked with “creating the false impression that a shrapnel bomb had exploded inside the City Room” and that “the pretend damage was manufactured sometime after the bang.”

The Inquiry report makes no mention of the “controlled explosion nearby at the Cathedral Gardens” that took place at 01:32 on May 23, 2017:

Source: YouTube

According to GMP, the controlled explosion related to “abandoned clothing, not a suspicious item.” Northern Rail’s Andrew Lowe (p. 4) and Claire Booth (p. 125) both mention it in their evidence, and Booth additionally mentions a police helicopter that was “so loud.” PC Dale Allcock (BTP) also mentions the police helicopter in Manchester: The Night of the Bomb. The controlled explosion and the police helicopter would have covered any loud noise coming from the City Room at the time.

This article, then, takes a closer look at Operation Manteline and how it may have served the overarching intelligence operation outlined in Part 10.

Operation Manteline

DCS Barraclough and DCI Pickering

Temporary Assistant Chief Constable (ACC) Russ Jackson appointed Detective Chief Superintendent (DCS) Simon Barraclough as the Senior Investigating Officer (SIO) for Operation Manteline “just after 00:00 on 23rd May 2017” (§23.134).

DCS Simon Barraclough. Source: Manchester Arena Inquiry

Barraclough was the head of the North West Counter Terrorism Unit (NWCTU), which became Counter Terrorism Policing North West (CTPNW) (01:00:20). The organisation “works very closely” with the North West regional station of MI5 (§24.13), meaning that the investigation fell under the aegis of MI5.

Paul Greaney QC remarked at the Inquiry that

As will be perfectly obvious, Mr Barraclough is aware of much operationally sensitive, and national security sensitive, material. Disclosure of that material publicly would be harmful to the national interest, because it would assist terrorists […] It might be that Mr Barraclough, from time to time, parks an answer […] (46:53)

Thus, Barraclough was not required to disclose certain information, in the interests of “national security.” The other way of looking at this is that Barraclough, and Operation Manteline, were shielded from effective scrutiny.

When asked at the Inquiry how the name for Operation Manteline was chosen, Barraclough claimed that it was “a randomly generated word” that has “absolutely no meaning” (53:00). Yet, “manteline” just so happens to be the French word (and old-fashioned English word, deriving from the Latin mantellum) for mantle, meaning cloak or “anything that covers completely.” Was there a clue in the name of the investigation that it was intended to cover something up?

Barraclough made a point of underscoring that he and his Operation Manteline team had been “wholly committed to this enterprise” (54:25). He even claimed to have delayed his retirement to be able to assist the Inquiry (52:30). He was clearly heavily invested in the enterprise.

Yet, despite his central role in Operation Manteline, Barraclough is barely mentioned in the Inquiry report, and receives only mundane treatment where he is mentioned, viz. his suggestion that it is “highly likely that SA [Salman Abedi] and HA [Hashem Abedi] fed off one another’s ideas and radicalised each other” (§22.61).

For the first two weeks, the investigation team worked around the clock, and ACC Jackson appointed Detective Superintendent William Chatterton and Detective Chief Inspector Andrew Meeks — both trained Counter Terrorism Senior Investigating Officers in NWCTU — to assist Barraclough (01:06:40), i.e. two more figures from the Counter Terrorism/MI5 nexus.

Vast resources were deployed from across the country during that initial period, leading to what Barraclough called a “colossal” investigation (§23.145). This created the impression that everything possible was being done to get to the bottom of who was responsible for the Manchester Arena incident and how it was facilitated.

We are supposed to be impressed by Operation Manteline because of metrics:

GMP estimated that more than 1,000 police officers, police staff and National Crime Agency officers were involved in the initial stages of the investigation. More than 16,000 actions were raised. During the course of the investigation, more than 17,000 exhibits were seized. In excess of 4,000 witness statements were taken. More than 20,000 documents were produced. There were 23 arrests under the Terrorism Act 2000. A total of 42 properties were searched. More than 900 digital devices were seized. (§23.143)

None of those figures say anything about the quality of the investigation, however. For example, none of the 23 arrests led to a prosecution. The last suspect was released without charge on June 6, 2017.

Davis (2024, p. 233) recognises that, despite the advertised scale of the investigation, only those at the very top would have known its true purpose, if that purpose were to conceal a conspiracy against the public. Compartmentalisation would have meant that the overwhelming majority of officers working on the investigation had no idea of the bigger picture.

Barraclough’s Deputy SIO was Detective Chief Inspector Sam Pickering (01:06:20).

DCI Sam Pickering. Source: Manchester Arena Inquiry

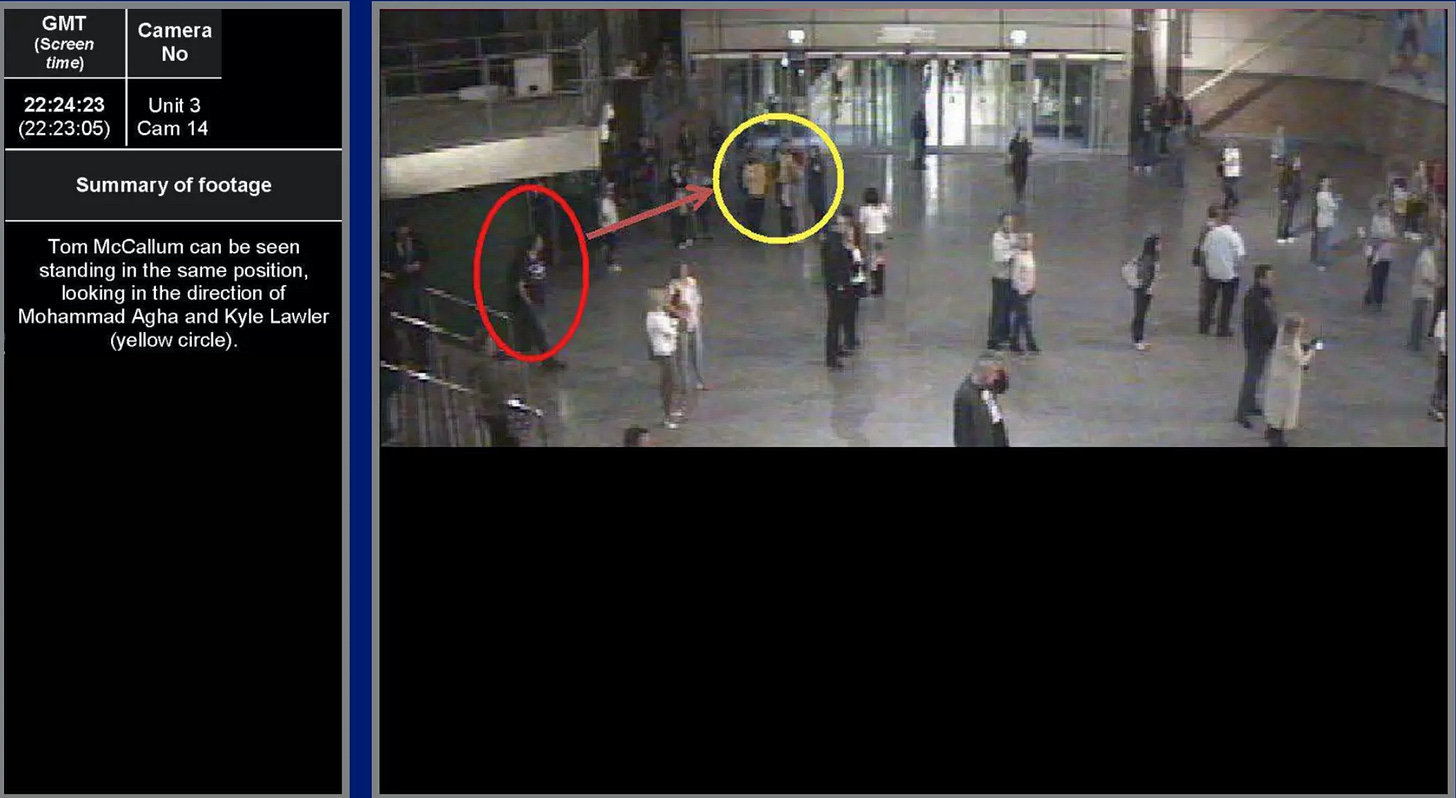

At the Inquiry hearings, DCI Pickering’s only role was to confirm the information shown on evidence provided by Operation Manteline, such as the layout of the Victoria Exchange Complex, Salman Abedi’s movements, and the content of the CCTV imagery provided. Mostly of his answers were along the lines of “yes, that is correct,” as Nicholas de la Poer QC described the CCTV imagery for the record.

DCI Pickering is not mentioned in the Inquiry report, thus going completely under the radar of the official account.

DS Teresa Lam and DI Michael Russell

Saunders writes in the Inquiry report:

The part of the Operation Manteline team supporting the inquests and subsequently the Inquiry was headed by Detective Superintendent Teresa Lam. Detective Inspector (DI) Michael Russell was responsible for those who gathered, collated and analysed the hundreds of hours of audio-visual material. (§19.60)

Saunders pays tribute to Lam, Russell, and those within their team for their “painstaking and protracted work” in “reconstructing the period post-explosion,” even though this must have been “highly distressing” (§19.61). Their work allegedly “enabled the clearest possible understanding of what happened to each of those who was killed following the detonation.”

As we will see towards the end of this series, there is a great deal of detail in the Inquiry report, particularly Chapter 18, concerning casualties and fatalities in the City Room, and the names of those who assisted (and in some cases covered) them. None of that information is independently verifiable by the public. It is important to note that DS Lam and DI Russell were primarily responsible for providing that information to the Inquiry.

We know that in at least one instance, that information was wrong. As we saw in Part 2, DI Russell told the Inquiry that Michelle Kiss and Ruth Murrell were standing next to each other at the moment of detonation, yet one second before the official detonation time on CCTV, we see Murrell standing on the steps to the mezzanine without Kiss by her side.

DI Michael Russell. Source: Manchester Arena Inquiry

DS Lam in early 2019 received the British Empire Medal for services to policing. She reportedly

led a team of 80 specialist officers providing personal support to families of the victims, was a key link between the police investigation and health service professionals and helped families to access the We Love MCR Emergency Fund.

Source: Manchester Evening News

As the primary point of contact between Operation Manteline and families accessing the emergency fund, and Operation Manteline and the Inquiry, Lam is a very important figure. Nevertheless, unless I have missed something, Lam was not called to give evidence to the Inquiry, and only gets two mentions in the Inquiry report.

Bomb Scene Manager Robert Gallagher

The first indication of the identity of the alleged perpetrator came at 01:58 on May 23, 2017, when a damaged bank card bearing Salman Abedi’s still intact name was officially discovered in the City Room by North West Counter Terrorism Unit Bomb Scene Manager, Robert Gallagher (§23.135). This was confirmed by DCS Barraclough at the Inquiry (p. 66).

Robert Gallagher taking the oath. Source: Manchester Arena Inquiry

The rapid discovery of perpetrator ID has been a motif in false flag terrorism since the (literally) unbelievable discovery of a hijacker’s passport on the day of “9/11.”

According to the police investigation, photographs were taken of Abedi, and an anonymous image assessment expert confirmed it was him (§23.136). Fingerprint analysis also confirmed it was Abedi, as did DNA comparison (§23.137). Barraclough confirmed all this at the Inquiry (01:39:30), as did Gallagher (pp. 78-79).

The precise timeline was given as follows:

Source: Inquiry report, p. 130.

Problematically, the public only has Barraclough and Gallagher’s word for it that Abedi’s body was present at the scene and identified through the means described. For example, if one wants to verify any of the information in the above table, then footnotes 104-110 display a variety of reference codes:

The live links for those codes can be found here. Although all the codes are different, they all lead back to the transcript of Gallagher giving evidence.

Therefore, it is important to be able to assess the credibility of Barraclough and Gallagher. Barraclough, for the most part, simply confirmed the statements made by Paul Greaney QC during the Inquiry hearings. His performance was deliberately bland and unremarkable.

Gallagher, on the other hand, made some specific, testable claims. For example, he claimed to have noticed “extensive damage to the fabric of the building” when he arrived in the City Room “at about 1.35 in the morning of 23 May” (p. 70). Yet, we know that there was minimal, if any, damage to the building at or around 22:35 on May 22, 2017 (see Part 2).

Even if we give Gallagher the benefit of the doubt that the damage had been caused before he arrived at 01:35 (perhaps by the “large group of officers” that entered the City Room at or around 00:58:47), then the damage was not “extensive.” Rather, it was confined to a single ticket office window and the area around it, the doors to the hospitality suite and the wall next to it, and the marks spotted by Pighooey. Gallagher must have known this, and appears to have exaggerated the extent of the building damage.

A “large group of officers” enter the City Room at 00:58:47 and line up in front of Inspector Michael Smith. Source: Richplanet.net

Conspicuously, Gallagher described the damage to one of the box office windows as looking “like gunshots” (p. 76). Were certain sections of the City Room (the box office window, the hospitality suite doors, and the wall next to them) shot up and later presented as having sustained shrapnel damage?

Gallagher told the Inquiry that the first broken glass panel from the skylight

came down around about 10 o’clock in the morning and then a second one came down. We had to vacate the City Room. We got extra PPE, hard hats, et cetera, to go back in. (p. 81)

However, drone footage from the start of June 2017 appears to show the City Room skylight completely intact:

Source: UK Critical Thinker (03:52)

Had the skylight been repaired, the media would almost certainly have propagandised the public with more stories about the alleged bombing. However, there do not appear to be any media reports of the skylight being repaired. Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that the skylight was not, in fact, damaged.

Gallagher’s claim about glass falling from the skylight was so poorly thought out that Paul Greaney QC had to preface a later session as follows:

Sir, as you will recall, the bomb scene manager, Mr Gallagher, gave evidence a little earlier today about a glass panel falling from the ceiling on to the floor at 10am on the 23rd. A concern has been expressed on behalf of some of the families to be assured that the glass panel did not fall on to their loved ones. I have had a chance to speak to Mr Gallagher and also to Mr Barraclough and they can be so assured, the panel did not fall on to any of the deceased. (pp. 133-134)

This rapid reassurance, which does not mention the second glass panel that allegedly fell, or the effects of the glass shattering on the floor, or what measures were taken to stop further glass panels from falling, seems fortuitous.

One would expect any panels that fell to have been closest to the detonation site, however, that could not have been the case:

Source: The Times, with my annotated estimation of the skylight’s position.

In sum, Gallagher does not appear to have been a reliable witness. Therefore, it is appropriate to treat his claims about the identification of Salman Abedi with caution.

Notwithstanding the aforementioned concerns, Gallagher was awarded a MBE in 2019 for his role in “manag[ing] GMP's forensic response to the attack including victim identification.”

After giving evidence to the Inquiry in December 2020, Gallagher made an unexpected career change, leaving his high-powered position in Counter Terrorism and joining the University of Central Lancashire in September 2021 as a lowly lecturer in forensic crime scene examination.

The Alleged Bomb

According to the Inquiry report,

The investigators recovered 29.26kg of metal nuts. A further 1.47kg of screws or cross dowels were also recovered. The investigation concluded that there were approximately 3,000 such items of shrapnel in total. (§23.142)

Thus, the nuts, screws, and cross dowels weighed 30.73 kg. The bomb mechanism, the TATP, and the rucksack materials would have weighed Abedi down still further. For context, Davis (2024, p. 195) notes that a large bag of cement in the UK typically weighs 25kg.

Abedi was young and fit, but also thin. The average male weight is 78.1 kg. Therefore, it is likely that Abedi was carrying the equivalent of over 40% of his own body mass on his back, if the investigation is to be believed.

Abedi can be seen walking on the station concourse and along the footbridge in this CCTV footage. Although the bag is heavy, he strolls along casually without gripping the front straps, as one would expect if he were carrying the equivalent of a bag and a half of cement.

Salman Abedi carrying his rucksack. Source: Richplanet.net

What happened to the 3,000 pieces of shrapnel? As analysed in Part 2, there is no credible primary empirical evidence of shrapnel damage to the City Room. For instance, in the image below, where are the nuts and bolts on the floor, or damage to the floor, or lighting damage, or damage to the walls and doors?

Source: Barr footage

According to the investigation,

The process of constructing the bomb was a complex one. It involved SA [Salman Abedi] altering the TATP from a relatively safe state to one that was highly unstable. It involved integrating that now unstable explosive into a device that SA was able to detonate. (§23.165)

Yet, it is evident that TATP was not used. A TATP explosion emits neither light, nor heat, nor smoke, yet Abedi’s device demonstrably generated all three (see Part 2).

Furthermore, if Abedi’s device were “highly unstable,” why would he wait around with it on the mezzanine for around an hour? What if it had accidentally detonated at the top of the McDonald’s staircase while the City Room was mostly empty?

At one stage, according to eyewitness Neal Hatfield, Abedi laid his rucksack horizontally on the ground (31:05). Why would he change its alignment from vertical to horizontal if it contained a “highly unstable” TATP concoction?

Saunders appeared to get irritated by such considerations at one point in proceedings, prompting a rapid shutdown of discussion:

Sir John Saunders: Okay, are there indications that, whoever did it, the Abedi brothers no doubt, that they followed the instructions to avoid blowing themselves up in the process?

Lorna Philp: Yes.

Pete Weatherby QC: I won’t take it any further. (p. 124)

All in all, Operation Manteline’s description of the bomb does not match the available evidence.

Therefore, there is no reason to trust the investigation’s claim that other bomb parts were discovered, including a Sistema 45910 switch (§23.160), a switch cover, a keypad, a micro chip, and pieces of battery.

Source: Operation Manteline

Given that building damage was fabricated, these items could easily have been planted.

Nuts and Bolts

The witness statements prepared by GMP repeatedly refer to nuts and bolts on the floor of the City Room. For example, PS Martin James Dunn (GMP) states

I recall at some point as we were treating her, a metal nut fell from her upper arm. [...] I noticed hundreds of metal nuts on the floor of the Foyer. (p. 3)

According to Robina Jones (ETUK), “I entered the City Rooms and saw [...] lots of bolts” (p. 2), and “I could see that she had shrapnel all over her” (p. 3).

PS John Whitaker (BTP) states

I had become aware that amongst the debris on the floor was a large quantity of nuts and bolts. I suspected these had been used in a device that had caused the explosion. (p. 2)

Member of the public Sarah Gullick’s witness statement contains the line “I saw metal nuts and bolts on the floor of the arena.”

Tacked onto the end of member of the public Helen Byrne’s witness statement is “Once [DPA] had got hold of her library book she showed me that there was a hole in it and to our shock there as [sic.] a nut/bolt stuck inside the book.” It reads as contrived.

At the end of member of the public Jean Forster’s witness statement we read: “I saw lots of nuts and bolts strewn all over the floor.” It, too, feels contrived.

In Travel Safe’s Philip Clegg’s second witness statement, we find “I had to move nuts and bolts from under myself, as they were imprinting on me.” Clegg’s second statement (dated January 23, 2019) is markedly different from his first (dated June 1, 2017), insofar it provides pages of detail with respect to events within the City Room (including the use of defibrillators). The original witness statement merely states that “On arriving at the foyer I began trying to provide assistance/aid to the victims and injured.”

Travel Safe’s Niall Pentony stated: “There were lots of nuts and bolts, shards of glass, some of the bolts were three inches long and had been sprained and bended.”

The sensible reply to such claims is to refer to primary observable evidence and to ask: Where is any clearly identifiable nut or bolt 12-15 minutes post-detonation?

Source: Hall, Table For Two (30:55)

Given that no nuts and bolts are clearly identifiable in the Barr footage or the Parker photograph, it is reasonable to question the reliability of the witness statements, and whether the references to nuts and bolts were introduced artificially.

Similarly, we might wonder about

CCTV

Operation Manteline made available to the Inquiry small amounts of CCTV footage (as opposed to still images). Some of it plays smoothly, e.g. this footage of Salman Abedi fluently crossing the footbridge with his rucksack on. Other footage plays more disjointedly, e.g. this footage from the City Room, or this footage showing Abedi walking down the Trinity Way tunnel at 18:34, both of which show approximately one image per second.

For the pre-detonation period, why was all the footage from every camera not released? What is there to hide?

For example, why was the 20:03 footage of Martin and Eve Hibbert entering the City Room not released (see Part 4)? Or, why was the 21:54 footage of Martyn Hett going to get a drink with his friend not released?

Martyn and Paul [Derrig−Swaine] went to get a drink at the bar shortly before the concert ended. Footage shows Martyn and Paul walking together on the concourse at 21.54. On the way back, Martyn stopped to chat to two women on the concourse as Paul went back into the concert. (pp. 7-8)

Instead, Operation Manteline went to great lengths to curate a “Sequence of Events” for dozens of specific individuals, typically based on selected CCTV images.

Example cover of a Sequence of Events. Source: Manchester Arena Inquiry (03:23:00)

As Davis (2024, p. 279) notes, the use of selected still images instead of video suggests a cherry-picking of evidence in an attempt to prop up the official narrative.

Even within the pre-detonation CCTV still images that were released, certain information is inexplicably marked “sensitive” and redacted:

Source: Richplanet.net

Source: Richplanet.net

What possible need was there to black out such a large area of the City Room six minutes and 37 seconds before the official detonation time?

One further anomaly relating to the CCTV imagery is the fact that Operation Manteline presented it using GMT (Greenwich Mean Time). As Pighooey has pointed out, the time should have been shown using BST (British Summer Time), which is one hour ahead of GMT.

What Time Was Detonation?

Further reasons to suspect that evidence was doctored by Operation Manteline have to do with the official detonation time of 22:31:00.

As noted in Part 2, the CCTV image below, officially captured one second before detonation, cannot be reconciled with the sparsely populated Parker photograph and Barr footage taken four minutes later, which show no evidence of a massive TATP shrapnel bomb having gone off in the middle of such a crowded room.

Source: Richplanet.net

Hall proposes that the actual detonation time was at or around 22:31:30, thirty seconds later than the official time (§4.13).

For example, the CCTV image below was captured at the war memorial on Victoria Station concourse at 22:31:09, officially nine seconds after the explosion, yet no one in it seems to have reacted.

Source: Richplanet.net

Virtually all of the CCTV cameras from which footage was seized displayed an incorrect time, which is why the Operation Manteline images show the “true” GMT time alongside the wrong time shown on camera. In other words, the necessary corrections to show the real time had been systematically made.

Nevertheless, at the Inquiry, Nicholas de la Poer QC, referring to the above CCTV image, claimed “It’s fair to say […] that this is one of the cameras in relation to which there is a very minor degree of doubt about the precise timing” and that it “may be immediately before or after the explosion” (01:37:00). DCI Pickering replied “I don’t believe it’s after, but there is room for manoeuvre.”

Any “room for manoeuvre,” however, simply means that the Manteline team did not do its job properly. Exact timings are essential for CCTV analysis. To be at least nine seconds out is inexcusable for a criminal investigation of this importance.

More likely, in my view, is that the correct timing adjustment was made, but that the significance of the nine-second discrepancy on this one image was not spotted.

The lack of response by those shown on the 22:31:09 image contradicts the Inquiry report’s claim that

When the bomb exploded at 22:31, four BTP officers were standing at the War Memorial entrance to the station concourse […] Within seconds of hearing the explosion, they began to move in the direction of the City Room. (§13.8)

This brings us to the responses of specific individuals to the sound of an explosion.

PC Jessica Bullough and PCSO Jon-Paul Morrey

BTP PC Bullough told the Inquiry that she left the war memorial “immediately” upon hearing the bang:

Paul Greaney QC: At the time of the explosion you were by the war memorial?

Jessica Bullough: Yes, correct.

Paul Greaney QC: Immediately on hearing it you ran onto platform 3?

Jessica Bullough: Yes, correct.

Bullough and PCSO Jon-Paul Morrey were captured running on CCTV at 22:31:37, at a spot approximately 30 metres away from the war memorial:

Source: Richplanet.net

Hall estimates that it would have taken seven seconds to cover that distance (§4.13), which is about right. For instance, if the average running speed for a 25-29-year-old female is 8.07 mph, or 3.61 m/s, it would take 8.31 seconds to cover 30 metres. As a policewoman, Bullough may have been marginally faster.

If the official timing of the bang at 22:31:00 were accurate, and if Bullough started running immediately (as she testified), she would have been in the position shown in the above image at or around 22:31:07, i.e., 30 seconds earlier than the time recorded on CCTV. From this Hall infers that the true time of the bang may have been thirty seconds later, i.e., 22:31:30 (§4.13).

Gareth Chapman

A similar example relates to Gareth Chapman, a ticket and merchandise seller (p. 26) who was on Victoria Station concourse at the time of the bang. According to the Inquiry report,

His [Chapman’s] child and the mother of his child were attending the concert. As shown [on CCTV], 52 seconds after the explosion, he is captured on the station concourse CCTV running to the City Room (§16.186).

Source: Richplanet.net

I have marked Chapman’s position above using the initials GC in the diagram below:

Unannotated Source: Volume 1 of the Manchester Arena Report, Figure 14

I have ringed the position of the war memorial and noted the 30 metre (7 seconds) distance ran by Bullough and Morrey, who were captured on CCTV at 21:31:37 in a similar position to Chapman 15 seconds later.

As a merchandise seller, Chapman would presumably have taken up a position in or near the shaded area, to capture concertgoers exiting from the walkway steps via the two entrances either side of the ticket office, i.e., not far from Bullough’s starting position.

He may even have been visible in the 22:31:09 image above, just a few feet away from Bullough near the war memorial:

Even if he had been located at the far end of the concourse, it would not have taken him more than 20 seconds to run to the position marked “GC.” So, why did it officially take him 52 seconds to reach that point?

More likely is that the bang happened around 22:31:30, Chapman saw the BTP officers nearby running towards the City Room, found someone to watch his T-shirts/bag (or just dumped them), and followed 15 seconds behind them.

Also, note the members of the public fleeing in the opposite direction:

Presumably, they were waiting on the train platforms when they heard the bang. Why did it take these women 52 seconds to run 30-60 metres? Based on the figures above, this should have taken 8-17 seconds. This, again, is consistent with a detonation time of 22:31:30, plus a brief time to react.

Niall Pentony and Phillip Clegg

Compare the two images below, taken at 22:30:56 and 22:31:32, respectively:

Source: Richplanet.net

Source: Richplanet.net

If the bang occurred at the official time of 22:31:00, why do Pentony and Clegg only just appear to be reacting at 22:31:32? The fact that they are only starting to leave their position is more consistent with a detonation time of at or around 22:31:30.

Pentony and Clegg are seen in front of the turnstiles at 22:31:32. Bullough and Morrey were there at 22:31:37. Chapman was there at 22:31:52. These three separate examples are mutually corroborating: those close to the turnstiles started to move at or around 22:31:30. It is unlikely that all five of these individuals, plus those fleeing in the opposite direction, chose to wait for 30 seconds or longer before running.

Kim Mckeown

Kim Mckeown, who attended the concert with her friend Izzy Aaron, told Hall in an interview that

Jo and Jane dropped us off and said we’d meet at these doors after the concert’s finished. So we met there, and we were there for about a minute after seeing them, and then the bomb went off. (§4.13)

“Jo and Jane” refer to Izzy’s mother, Jo Aaron, and her mother’s friend, Jane Tweddle. Here are the four of them captured one second before the official time of the explosion:

Source: Richplanet.net

18 seconds earlier, Kim McKeown and Izzy Aaron were not present in the City Room:

Source: Richplanet.net

Jane Tweddle and Jo Aaron met Kim McKeown and Izzy Aaron at 22:30:58 (p. 29). This, however, is not “about a minute” before detonation: it is two seconds. If detonation occurred at or around 22:31:30, however, there would have been a distinct time lag such as that recollected by McKeown.

According to the official account,

They then turned from the box office windows to walk to the Trinity Way exit. Jane was walking next to Joanne on her right and Isabella and Kim were walking next to Joanne on her left. (p. 29)

This is not what we see at 22:30:59, however. Again, the additional time would have allowed for the four of them to be seen in those positions.

The First 999 Callers

Had the detonation take place at 22:31:00, one might have expected the first 999 calls to have been made during the first minute. As it was, however, the first call was made at 22:32 (§14.12) and the second at 22:32:40 (§13.141). Again, this seems more in keeping with a detonation time of 22:31:30.

Implications of a False Detonation Time

If Hall is correct that the real detonation time was ca. 22:31:30, as opposed to the official time of 22:31:00, then not only is this further evidence of foul play in relation to Operation Manteline, but it also means that “no CCTV images have been released of the City Room, from a period 30 seconds before the actual blast time” (§4.13).

If so, then what was going in the City Room during those vital 30 seconds, and why has it been kept secret from the public?

For example, Hall contends that 30 seconds would have been long enough for stewards to divert the crowd away from the doors, as per eyewitness testimonies (31:20). This would have stopped the swell of people entering the City Room and given many of those present in the 22:30:59 CCTV images time to vacate the room, or at least the area close to the concourse doors and the official detonation spot.

That said, there were still numerous people (gathered mostly on the left hand side of the 22:30:59 image below) who were apparently waiting to meet concertgoers and they presumably would have remained where they were. I am not aware of any accounts by those people of having been instructed to exit, or of anyone noticing the City Room thinning out before the bang. Even if there are question marks over some of those people, such as Ruth Murrell (see Part 2), there would surely have been many people

Source: Richplanet.net

30 seconds would allow time for Salman Abedi to put down his rucksack and flee the scene, as reported by at least two eye witnesses (see Parts 2 and 6).

30 seconds would also allow time for any potential crisis actors to get in position. Lest this suggestion be dismissed as preposterous, remember that it only took 15 seconds or so for at least a dozen crisis actors in the Iraqi hoax shown in Part 4 to rush in from off stage and create the misimpression of first responders trying to help injured victims following a car bombing. That was one year before the incident in the City Room, establishing proof of concept. The controversial issue of crisis actors will be revisited later in this series.

The Strange Case of Hashem Abedi

As a result of Operation Manteline, Salman Abedi’s brother, Hashem Abedi, was extradited to the UK on July 17, 2019 (§23.140). Innocent until proven guilty,

HA [Hashem Abedi] refused to answer the questions asked of him by Operation Manteline investigators. He provided a statement. In that statement he denied holding extremist views or being a supporter of Islamic State. He denied any involvement in or knowledge of the [Manchester] Attack. (§23.141)

For reasons that remain unclear, Hashem Abedi bizarrely refused to testify at his own trial, and was found guilty by a jury, although we only have the Sentencing Remarks to go on and no details of what was said in court, apart from reports by an untrustworthy legacy media. Central Criminal Court case records are not released for at least twenty years after trial, so there is no prospect of this information coming to light in the near future.

Hashem Abedi’s refusal to mount a defence at this trial — he even sacked his legal team — seems most peculiar, given that he could, in theory, have mounted a very strong defence. For example, his legal team could have argued that he was not in the country when the attack happened; that he had no idea what his brother was up to; and that his brother had asked him to buy certain items, lying to him about what they were for. The fact that he made it as easy as possible for the jury to convict him (rather than vigorously protesting his innocence) suggests he may have been an asset, like his father, as does the fact that he has not appealed the guilty verdict.

A trial and a guilty verdict was necessary in law to establish that a crime had been committed. As we have seen with the Richard D. Hall case, that legal precedent can and has been used to silence those who question the official version of events.

Following his conviction, when interviewed by members of the Inquiry Legal Team (§23.149), including Nicholas de la Poer QC, Hashem Abedi “admitted that he was a supporter of violent jihad in that he supported the institution of Sharia law through violent means” (§23.150). Apparently, when asked “What actions have you taken to support Islamic State?” he answered “The Manchester attack” (§23.151). He even read out a new statement that Saunders describes as “Islamic State propaganda” (§23.153). All of this represents a complete U-turn on his previous statement.

We do not know of the circumstances under which that confession was obtained. If he was an asset, perhaps the whole thing was pre-scripted.

Alternatively, in a different context, approximately one third of the references in the flawed 9/11 Commission Report were based on confession extracted from Khalid Sheik Mohammed under torture. This is not to claim that Hashem Abedi was tortured. But it is to suggest that something may have happened to him between his trial — up to and including which point he had adamantly maintained his innocence — and his confession, by which point he had lost his freedom and was potentially open to extortion. As with the circumstances of his trial, the public has no way of knowing what really happened.

Saunders bluntly finds, however, that “HA admitted that he had played a full and knowing part in the planning and preparation for the Attack” (§23.152).

Timeline of key events relating to Hashem Abedi. Source: Inquiry report, Volume 3, p. 130.

Was Martin Hibbert Roped in by Operation Manteline?

At the Inquiry, Hibbert thanked GMP’s Michael Russell and Mark Crawley for putting together the Sequence of Events supposedly showing what happened to him after he had no recollection of being stretchered out of the City Room (1:17:15).

It was on the basis of having allegedly reviewed that Sequence of Events that Hibbert made his second witness statement to GMP on July 8, 2021, which dealt with events post-detonation, including his daughter Eve’s injuries.

Only on that basis was Hibbert called to give evidence to the Inquiry a fortnight later (see Part 7). Thus, Hibbert seems to have been deliberately positioned by DI Russell, and a script appears to have been handed to Sophie Cartwright QC for Hibbert to endorse at the Inquiry.

We should not forget, in that context, that while GMP was dealing with Hibbert on July 8, 2021, supposedly in relation to his Sequence of Events, it also asked him for his ex-wife Sarah Gillbard’s contact details so that it could investigate Hall’s visit to her home on or about September 1, 2019. GMP visited Gillbard on July 21, 2022, the day before Hibbert appeared before the Inquiry. It seems unlikely that the two matters are unrelated.

More likely is that matters with the Hibberts were only “stirred up” by GMP, as Hall’s barrister put it during his trial, because the impact of Hall’s book and film was beginning to become noticeable. It seems the groundwork was being prepared for the eventual coordinated attack on Hall, in which Eve’s injuries would be instrumentalised to play a central role (viz. her vulnerability to “harassment”).

According to Cartwright, Hibbert gave his first witness statement to GMP in April 2021. Then, on May 22, 2021, he posted a photograph of himself and Eve at San Carlo restaurant, the first time he had done so since 18:53 on May 22, 2017:

Then, in July, he gave his second witness statement in which Eve’s injuries were introduced. Was he told after his first statement that Eve would need to feature more prominently in his account?

Conclusion

There are numerous reasons to suspect the role of Operation Manteline.

We know that the evidence of building damage submitted to the Inquiry by Operation Manteline was fabricated.

North West Counter Terrorism Unit head, DCS Barraclough, who led the investigation, barely features in the Inquiry report, and his deputy, DCI Pickering, is not mentioned at all.

DS Lam and DI Russell were responsible for providing the Inquiry with the key information in relation to the post-detonation period. However, we know that at least some of that information was wrong, and we also know that other Operation Manteline evidence for that period was unreliable.

For example, although NWCTU’s Robert Gallagher told the Inquiry about “extensive damage to the fabric of the building,” including the dubious claim that the skylight had shattered, there is strong empirical evidence to the contrary. Why, then, should we trust Gallagher’s claims that Salman Abedi was identified through multiple means? Remember, all the evidence cited in the Inquiry report in relation to the identification of Abedi traces back to Gallagher.

The failure of Operation Manteline to release all the pre-detonation CCTV footage is suspicious, as are the pre-detonation redactions and the scale of the post-detonation redactions.

The investigation’s claim that Salman Abedi was carrying a bomb weighing well over 30kg on his back (approaching half his own body weight) does not comport with CCTV evidence that shows Abedi moving fairly fluently. Despite most of that mass officially consisting of bolts, screws, and cross-dowels, there is no evidence of shrapnel damage to the City Room as of 22:35 on May 22, 2017.

The official detonation time of 22:31:00 could be wrong. The number of people in the City Room one second beforehand cannot be reconciled with the 17 or so people lying on the floor in the Barr footage and Parker photograph. The cases of PC Jessica Bullough and PCSO Jon-Paul Morrey, Gareth Chapman, Niall Pentony and Phillip Clegg, and Kim McKeown suggest that the true detonation time may have been 30 seconds or so later, allowing time to manipulate whatever was happening inside the City Room.

The strange case of Hashem Abedi, who was extradited to the UK on the basis of evidence provided by Operation Manteline, raises questions regarding why he did not testify in his own defence, and why he completely changed his story after being found guilty. Given that the available evidence is inconsistent with a TATP bomb, the protracted backstory fed by Counter Terrorism about how the Abedi brothers built a TATP bomb on the Islamic State model seems questionable.

It seems likely that Martin Hibbert, whose Sequence of Events was curated by DI Russell, was roped in by Operation Manteline between April and July of 2021 with a view to making sure that his and Eve’s injuries featured at the Inquiry. It was probably not a coincidence that Manteline investigators first took an interest in Richard D. Hall at that time.

All in all, the various anomalies and discrepancies in the police investigation are consistent with the hypothesis of an intelligence operation orchestrated by MI5 and the NWCTU branch of Counter Terrorism.

Thanks for putting this together.

If I may, I'd like a further comment regarding the timelines.

It seems to me that police , and other, bodycam footage would be more likely to have verifiable timestamps.

I'm wary of jumping to conclusions hence a comment from yourself on the absence, accuracy, and integrity of any bodycam footage would be welcome.