Part 11 - Operatives

Introduction

In Part 10, I introduced Hall’s schema showing how a national security agency, such as MI5, could intervene at multiple levels (including the emergency services, the police investigation, the Inquiry, and the media) to be able to stage a fake terrorist attack. I presented evidence that the Manchester Arena incident had much in common with an exercise, not least Exercise Winchester Accord, which preceded it a year earlier. I discussed Hall’s theory that the City Room had been turned into a controlled and managed environment. I noted the apparent fabrication of a crime scene after it was taken over by Counter Terrorism. And, following Hall, I explained the possible motives for staging such an attack.

In this article, I explore some of the individuals who were present in the City Room at key moments on May 22, 2017, whom Hall suspects of being operatives, i.e. secret players in the intelligence operation. They are:

Salman Abedi

Martin McGuffie

Andrea Bradbury

Dave Middleton

Darron Coster

Inspector Michael Smith

Ian Parry

I also ask questions about nine other ETUK Staff who were present in the City Room within minutes of the detonation.

Needless to say, I do not have any proof that any of these individuals were in fact operatives, nor am I accusing them of anything.

However, it is worth considering Hall’s evidence in relation to them, because a coherent picture does emerge that is consistent with his staged attack hypothesis.

Much of the evidence discussed here is taken from Hall’s Manchester on Camera (2023), to which I have not previously drawn attention. I strongly recommend that you watch it. In just over one hour, Hall explains the ingenious CCTV viewing app that he developed and highlights the most important evidence that he identified from the CCTV imagery.

We should be grateful for the months of work that went into this, as it involved Hall going through over 4,000 pdf documents released by the Inquiry, extracting 806 CCTV images and the accompanying “summary of footage” for each one, and putting them together in such a way that they can be viewed chronologically by area of the venue, CCTV camera, or item of interest (such as specific individuals or groups), or a bespoke combination of these things.

It is a brilliant way of countering the Inquiry’s attempt to obfuscate what the CCTV imagery reveals, and because the Hibberts are not present in a single one of the 806 images, the app does not appear to have fallen under the terms of the injunction.

Richard D. Hall, Manchester on Camera (2023)

Salman Abedi

Hall mentions 20 occasions between 2010 and 2023 when Salman Abedi was reported as being “on MI5’s radar” (§4.11). But, Hall asks, was Abedi merely on their radar, or was he actively working for the British security services?

We know, for instance, that Abedi and his father, Ramadan (rumoured to have been a MI6 asset), were part of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, and that the UK Government admitted it was “likely” still in contact with former members of that group despite it being banned in the UK.

We also know that every false flag operation needs its scapegoats, preferably Muslim ones in the “War on Terror” context, as we saw with “9/11” and “7/7.”

As always seems to be the case, the perpetrator was known in advance to the security services: “some time before the Attack, the Security Service had information which transpired to be relevant to SA’s [Salman Abedi’s] plan and yet took no action in response” (§24.9).

If Abedi were working for British intelligence, then his actions on the night of May 22, 2017, as theorised by Hall and described in Parts 2 and 6, would be entirely consistent with Hall’s “staged attack” hypothesis.

If Hall is correct, then, rather than being a real suicide bomber, Abedi set up a getaway vehicle, hid out of sight of CCTV, then, at 22:30, walked across the City Room, placed his rucksack below the CCTV camera near the merchandise stall, and ran off before the device it contained detonated. Judging by police radio communications from the night (time stamp 01:11:00), the getaway vehicle was driven off at or around 23:54 and was pursued by police. We do not know what happened to the driver.

Martin McGuffie

Some of the most remarkable observations Hall makes in Manchester on Camera have to do with Martin McGuffie, an innocuous figure who sits reading a book in the City Room for most of the duration of the concert, supposedly waiting to meet his partner and daughter. It seems doubtful that anyone would ever have noticed McGuffie, were it not for Hall. I certainly did not, despite spending hours carefully studying the CCTV imagery of the City Room.

McGuffie had 22 year’s service in the Queen’s Lancashire Regiment, and some time between May 2017 and October 2020 became “a police officer in Manchester.” So he is both ex-military and GMP — not your average civilian.

McGuffie can first be seen on CCTV walking along the footbridge, alone, at 19:17:48, about to enter the City Room. He told the Inquiry that his partner and daughter had entered the Arena at 18:45, but there is no CCTV evidence of him seeing them off. He told the Inquiry that it was too far for him to travel home and back again, so he chose to spend the next few hours sitting by the steps reading his book:

Source: Richplanet.net

In a series of CCTV images up to 19:59:32, McGuffie remains in the same spot reading his book, but at 20:04:02 he is no longer there. He is next seen back in position, reading his book, at 20:30:11. The Inquiry did not ask him where he went.

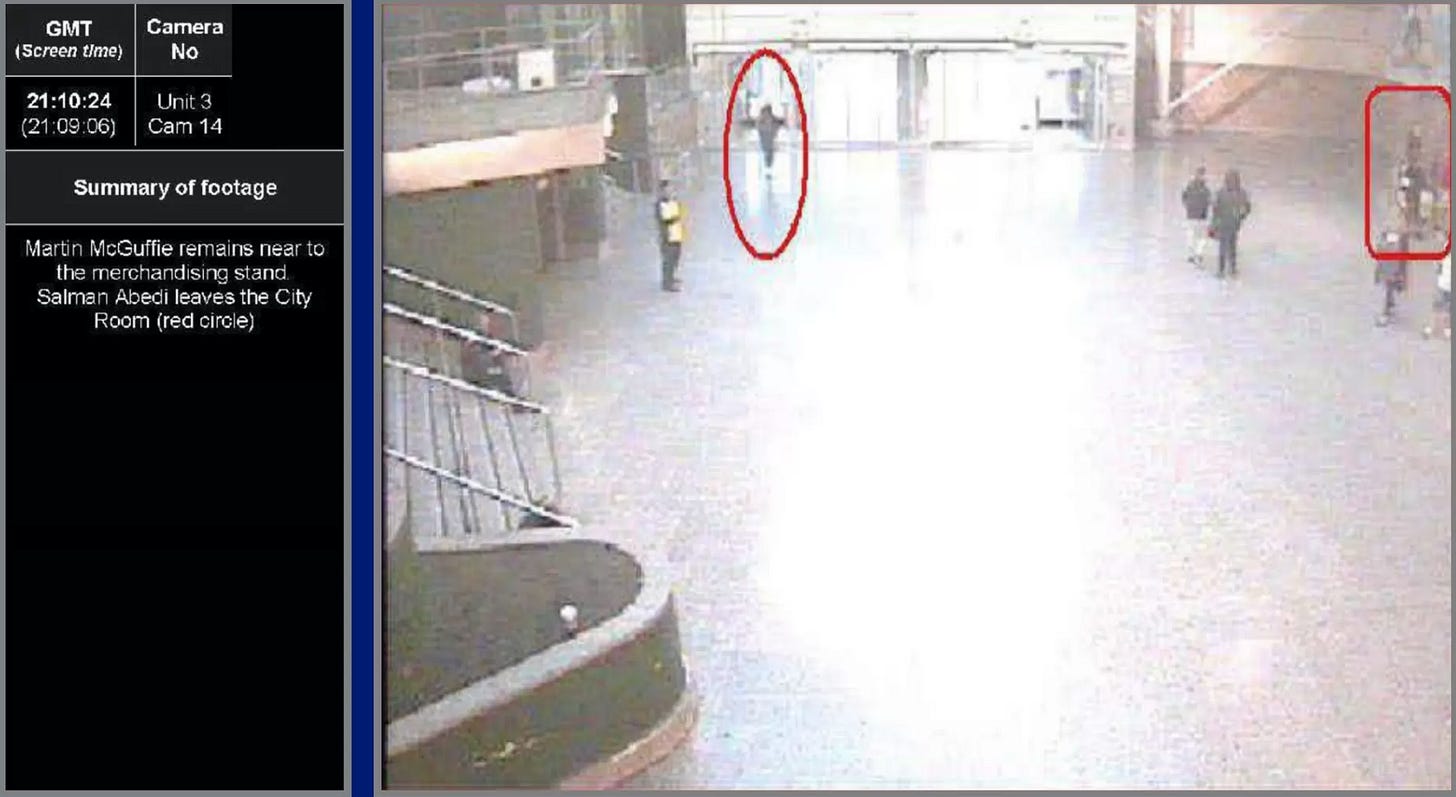

At 20:51:35, Salman Abedi is seen entering the City Room. He is then seen going up the steps next to McDonald’s, where he is thought to have waited at approximately the position marked by the green arrow below, before being captured on CCTV exiting the City Room at 21:10:33.

Source: Hall, Manchester on Trial

At 21:08:26, McGuffie is seen, rather oddly, at the corner of the merchandise stall. We know it is him because he is identified next to the merchandise stall at 21:04:21.

McGuffie is seen at the corner of the merchandise stall in the top right of the image. Source: Richplanet.net

What was he doing there? McGuffie told the Inquiry that he wanted to stretch his legs. Hall notes, however, that, from that location, McGuffie would have had an unimpeded view of Abedi at the top of the steps. This is correct. I have marked his line of sight to the top of the steps in blue below. I have also marked where else was visible from the merchandise stall in green:

Unannotated source: Volume 3 of the Inquiry report, p. 132.

Was he checking on Abedi? At the Inquiry, McGuffie explicitly denied having seen Abedi from that position (19:15). Yet, at 21:10:24, he is seen further towards the corner of the room with a clear line of sight to Abedi, who walks down the steps and towards the exit.

After Abedi left the City Room at 21:10:33, McGuffie is seen back in his original position reading his book at 21:14:25, where he apparently remained until 21:59:26.

Abedi returned to the City Room at 21:33:08, having apparently visited the Metrolink station for some unknown reason. As discussed in Part 6, it is Hall’s contention that between 21:33 and 21:52, Abedi went to move his getaway vehicle, a grey Audi, close to the Arena on Cheetham Hill Road. This presumably would have entailed him walking straight past McGuffie on his way back via the Trinity Way tunnel, but there is no publicly available CCTV imagery of Abedi during this period.

At 22:02:11, McGuffie can be seen heading towards the merchandise stall once more:

McGuffie is centre right in the CCTV image above. Source: Richplanet.net

The next available image of him, captured at 22:02:48, shows him walking back again. During the intervening 37 seconds, Hall speculates, McGuffie may have gone to check on Abedi again. However, he may not have seen him, as Abedi seems to have moved from the top of the McDonald’s step to a place in front of the JD Williams store, where eyewitnesses report that he lay down.

The cross marks Abedi’s location at 22:12, according to Volume 1 of the Inquiry report (Figure 3).

McGuffie is next seen heading up the main steps to the mezzanine at 22:09:20:

Source: Richplanet.net

He is seen turning right at the top of the steps at 22:09:32 (the CCTV time below is 18 seconds out):

Source: National Archives

At the top of the steps, McGuffie told the Inquiry (19:50) that he accidentally bumped into Salman Abedi, who was on the floor. Yet, from his position at 22:09:32, he would have a clear line of sight across the mezzanine. How did he “accidentally” bump into a man lying on the floor with a large rucksack?

McGuffie added that he was looking for the toilet, despite having already been told that the nearest one was at the train station downstairs. His testimony defied credibility when he claimed that Abedi asked him if he was looking for a toilet and that the nearest one was at the station downstairs (17:00). As Hall observes, if McGuffie really was trying to find a toilet, why did he first walk towards the merchandise stall?

McGuffie can be seen having descended the McDonald’s steps a minute later, at 22:10:26, and he told the Inquiry that he did indeed then go to find the toilet.

McGuffie can be seen returning to the City Room at 22:14:49, walking purposefully towards the bottom left of the image:

Source: Richplanet.net

However, 45 seconds later he has vanished, and CCTV imagery does not show him returning to position to read his book:

Source: Richplanet.net

Although McGuffie was officially present in the City Room at the moment of detonation, there are no further CCTV images of him waiting to meet his partner and daughter.

Suspiciously, even though McGuffie is named on CCTV imagery and gave evidence at the Inquiry, he is not mentioned in the Inquiry report. Public sightings of Abedi up until 22:00 are mentioned (§1.35), as is Christopher Wild’s encounter with Abedi at 22:15 (§1.48), but McGuffie’s encounter with Abedi at 22:09 is omitted.

Andrea Bradbury

Andrea Bradbury served for 30 years in the police, the last eight in counterterrorism, retiring two months before the Manchester Arena incident (§17.29; p. 73).

Bradbury officially drove her 15-year-old daughter with her friend and her friend’s mother, Barbara Whittaker, to the concert (§17.29). Not mentioned in the Inquiry report is that Whittaker’s husband, Mark, was also in counterterrorism, Bradbury knew him through work (p. 105), and she called him not long after the detonation (p. 142), before meeting him at GMP HQ.

Bradbury, Whittaker, and their daughters can officially be seen on CCTV entering the Victoria Exchange Complex via the Trinity Way tunnel at 18:22:27, although only Bradbury is clearly identifiable. She herself told the Inquiry “the girls are just ahead, you wouldn’t recognise them now because they’re so young. In fact, I struggled to recognise them this year, in August” (p. 108), which seems like a strangely distancing remark.

At 21:52:17, Bradbury and Whittaker are seen ascending the steps to the footbridge at the train station en route to the City Room. At 21:54:34, they are seen peering through the doors to the concourse:

Source: Richplanet.net

They remain at that approximate location for around 12 minutes, until 22:04:20, when they are described in the summary of footage as “leaving the City Room.”

Bradbury and and Whittaker are seen returning to the City Room from the stairs leading down to the Trinity Way tunnel at 22:15:35. Bradbury told the Inquiry that she had gone to try to move her car closer to the Arena “for the quickest exit” (24:30).

Hall astutely observes that this is precisely what Salman Abedi appears to have done with his getaway vehicle minutes earlier, between 21:33 and 21:52, and that Abedi, too, would have used the Trinity Way tunnel (see Part 6). Was Bradbury checking that Abedi had completed that task? She told the Inquiry that she did not actually move her own car, which would be consistent with this.

Hall asks whether Bradbury was “part of an operation which was conducting a staged attack, and there to observe and report back on the proceedings?” (§4.11). On the balance of evidence, that possibility cannot be discounted, nor can Whittaker’s potential involvement in it.

Further Information on Bradbury

Bradbury was one of just a few reported survivors called to give evidence at the Inquiry. What are the odds that she should be a Counter Terrorism specialist?

The Inquiry report notes that, at the time of the “massive blast,” Bradbury and Whittaker were “near to the merchandise stall” (§17.30), which, like the enormous poster behind it, remained completely undamaged (see Part 8). Bradbury described a “big white flash” and said it felt like her legs had been hit by a garden strimmer (§17.30).

According to Hudgell Solicitors, “When Salman Abedi detonated his device she [Bradbury] was just a matter of feet away.” Although Bradbury described her body as “peppered and dotted” with shrapnel and her calves as having been “strimmed with a wire garden strimmer,” she somehow managed to locate her daughter and her friend’s daughter, having “crawled to the Arena bowl to find them” (§17.31, my emphasis).

Seemingly unperturbed by her injuries, Bradbury went back into the City Room and “telephoned the on call counterterrorism officer in Lancashire [Mark Whittaker] to provide an account from the scene. She did this three times” (§17.32).

Despite the shrapnel in her body and the damage to her calves, and as though three phone calls were not enough, Bradbury then took a taxi to GMP Headquarters (where the counterterrorism unit is based) to explain in person what had happened (§17.33). There, she claims have spoken to a police officer who was “Gold,” yet Gold Commander Deborah Ford “said that this was not her” (§17.33). Bradbury’s recollection of events was, thus, inaccurate.

Only after performing her counter-terrorism duties did Bradbury go to hospital; she apparently has permanent nerve damage to her legs (§17.34).

Bradbury’s account is clearly implausible. If she were one of the closest people to Salman Abedi’s TATP shrapnel bomb, she would have been killed, or at least very seriously injured. She would not have been able to prioritise going to GMP HQ over going to hospital.

Later, Bradbury was involved with Manchester mayor Andy Burnham and Brendan Cox, the widower of the former MP Jo Cox, in pushing for Martyn’s Law, which, if passed, will introduce draconian new security measures to venues over a certain size in the UK.

In a Manchester Evening News article in 2019, Bradbury claimed that she had been knocked unconscious by the bomb, that the children were found at the nearby Arndale Centre and Printworks (not the Arena), and that her handbag had prevented a piece of shrapnel hitting the centre of her back, saving her life. As we saw with Martin Hibbert in Part 7, such shifting and exaggerated recollections of events give cause for suspicion.

In sum, Bradbury’s counter-terrorism background, her questionable account of surviving a TATP shrapnel bomb from close range, and her links to Hudgell’s, GMP, Burnham/Cox, and the Inquiry make her a figure of interest.

Dave Middleton

Middleton led the Showsec staff working in the City Room and on the footbridge. Showsec is described in the Inquiry report as “the crowd management and security company” utilized by the venue owner, SMG (p. vi).

Hall notes that if his staged attack hypothesis is correct, Middleton must have been a key player (31:40).

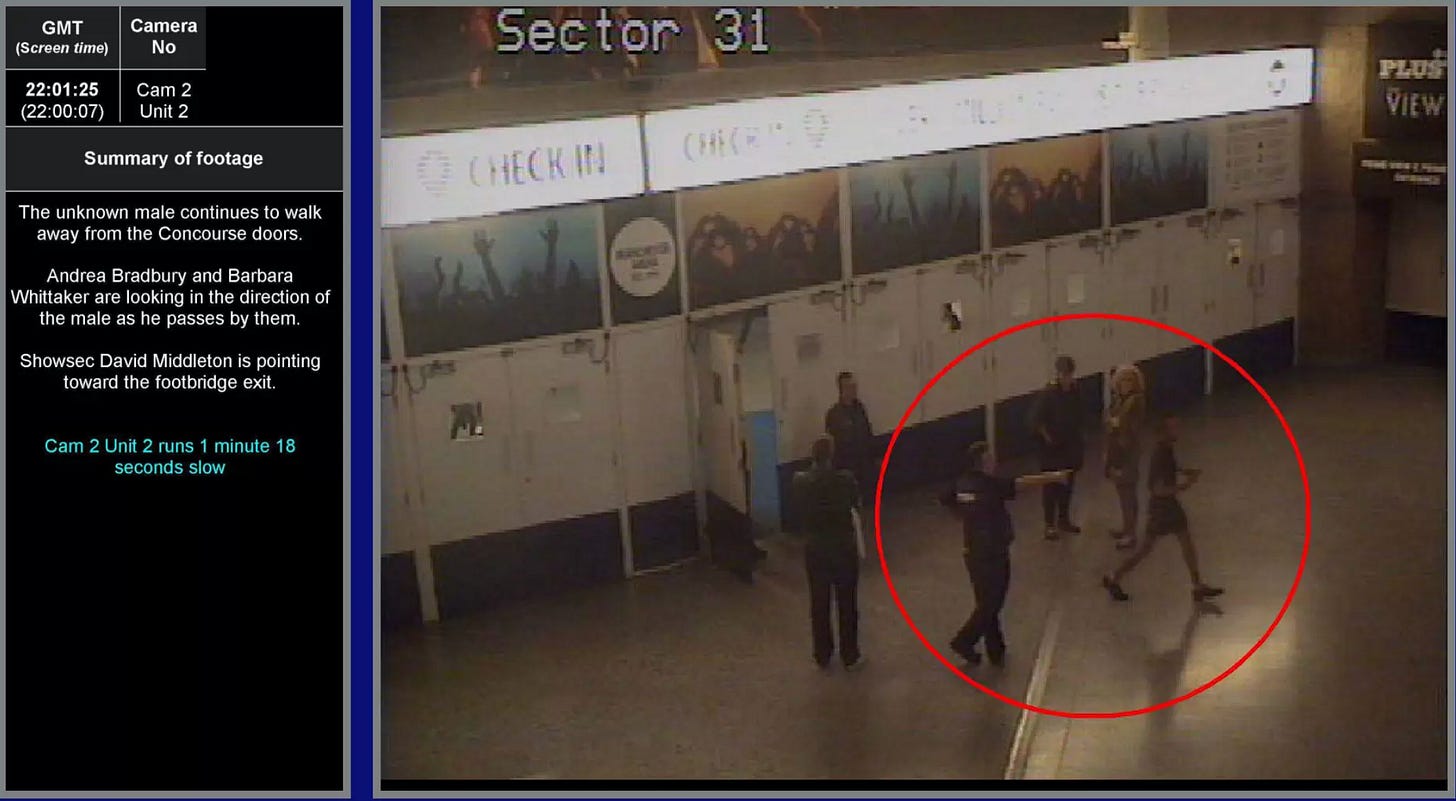

Middleton adopted a position in front of the doors to concourse about half an hour before the concert ended, next to where Bradbury and Whittaker stood for a time:

Middleton, Bradbury, and Whittaker, all within the red circle. Source: Richplanet.net

As the crowds exited at the end of the concert, Middleton appeared to signal to Jane Tweddle and Jo Aaron (at the bottom of the image below) to move towards the ticket office:

Source: Richplanet.net

Previously they and the person behind them had been standing to the left:

Source: Richplanet.net

Hall speculates that this could have been to clear a path for anyone approaching from the coloured area below, for which post-detonation CCTV footage was inexplicably redacted. Tweddle and Aaron’s change of position is marked by the red dots.

Source: Manchester on Camera (51:12)

Clearly, something of interest must have been happening in that area, otherwise why was it necessary to redact it for nine seconds, six minutes before the detonation?

Source: Richplanet.net

In Part 10, we considered three eye witness reports that “stewards” and “security men” had blocked access to the City Room from the Arena concourse before detonation. Although we cannot say for sure, they were most likely Showsec staff. For example, here are Showsec staff two minutes after detonation, with the crowds having apparently been directed away from the City Room exit:

Source: Richplanet.net

But if Showsec staff diverted the public away from the City Room before detonation, were they following a last-minute instruction by Middleton, or was Middleton’s entire team (or at the very least Jordan Beak and Daniel Perry as senior members of staff) in the know?

To my knowledge, none of Middleton’s team gave interviews to the media; unlike so many participants in the event, they maintained a low profile.

Mohammad Agha as Fall Guy?

Mohammad Agha was not an operative, but it is possible that he was set up to shoulder some of the blame for Showsec failing to stop Abedi from successfully detonating his device.

Agha was “told” — presumably by his supervisor, Dave Middleton — to stand in front of the Grey Doors the entire evening (§6.124), even though there was no need to do so (§6.125). This was the first time he had performed that role (§2.54).

Source: Volume 1 of the Inquiry report, Figure 15

For reference, the Grey Doors provided non-public access to the platform overbridge:

Source: Volume 1 of the Inquiry report, Figure 14

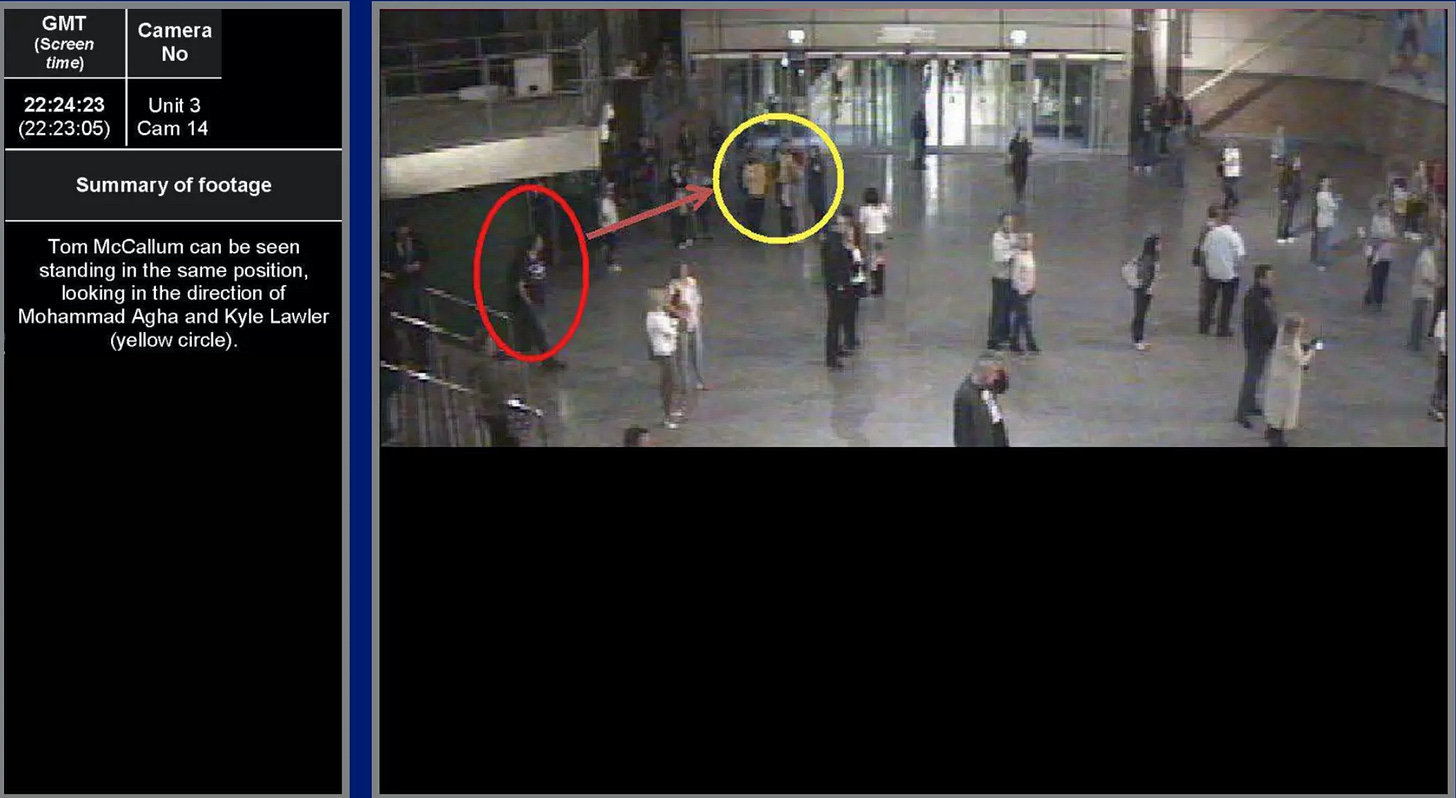

Agha is criticised in the Inquiry report for failing to take adequate action when notified of Salman Abedi’s suspicious behaviour at 22:15 by a member of the public, Christopher Wild, who claims to have been “fobbed off” by him (§1.50). This was corroborated by another member of the public, Thomas McCallum, who overheard the conversation and thought that Agha was “really quite dismissive” (§1.50).

Was this a fair assessment? At the Inquiry, Agha denied “fobbing off” Wild:

I was telling him not to worry, I’ll look into it [..] When it comes to the security role, you are not supposed to panic people [...] I would rather look into it myself and then tell someone a bit higher than myself to look into it. (01:17:30)

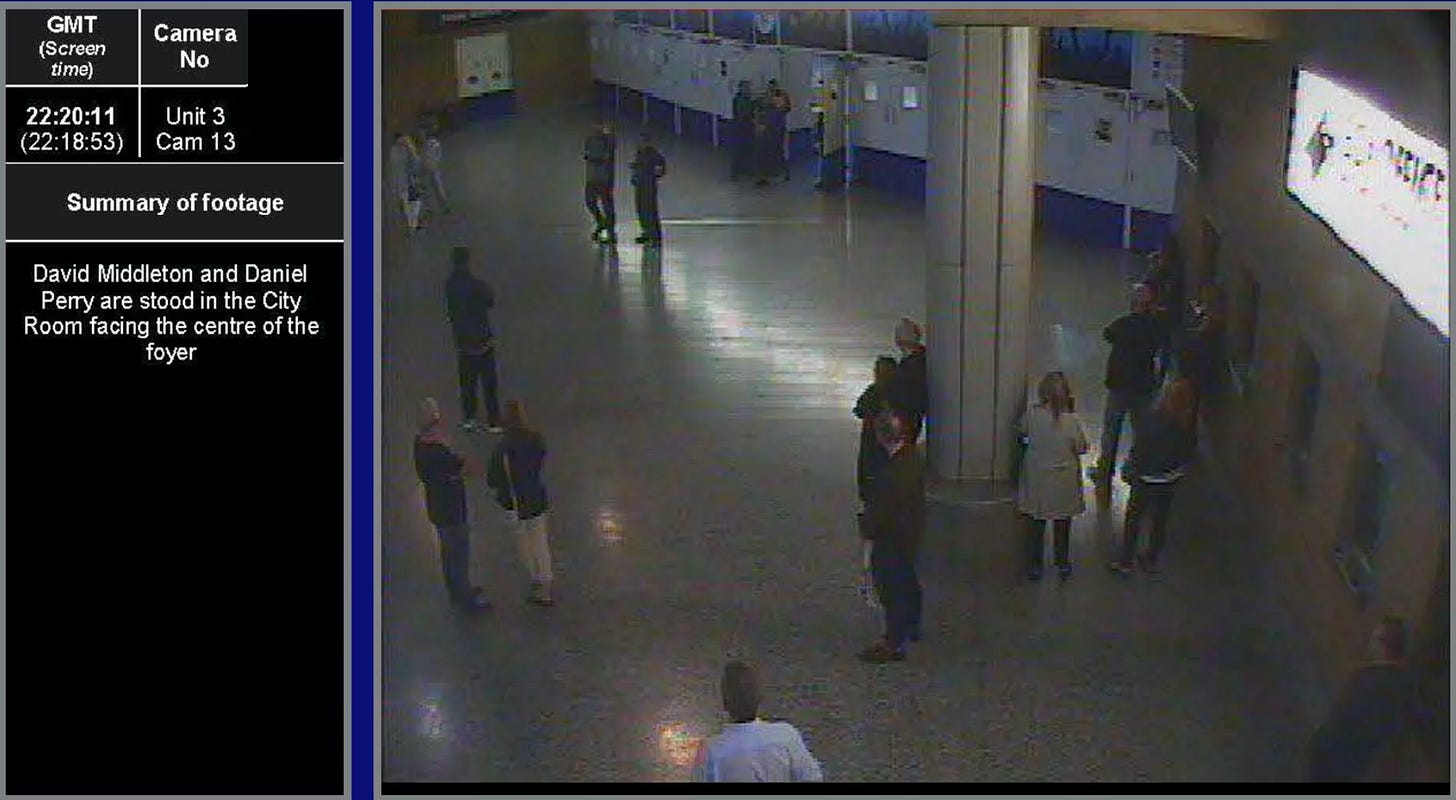

Agha can be seen on CCTV trying to attract Middleton’s attention by waving his arms three times, at 22:19:14, 22:20:03 and 22:20:11. Prior to that, Middleton can be seen on CCTV, at 22:17:00, 22:17:02, and 22:17:41, 22:18:26, facing away from Agha.

Unusually, the CCTV footage (as opposed to selectively released stills) for this sequence was played at the Inquiry. If one adds 68 seconds to correct for camera lag, it is clear that Middleton was not in a position to be flagged down by Agha between 22:17:00 and 22:19:14.

Wild is seen on CCTV walking away from Agha at 22:15:34. At that moment, Middleton was facing towards them. But it is possible that Middleton turned away as Agha was taking a moment to process what he had just been told. There is no publicly available CCTV imagery showing Middleton’s position between 22:15:35 and 22:16:59.

Agha told the Inquiry that, during one of his three arm gestures towards Middleton, “We’ve both got eye contact, we’re both looking at each other” (01:25:50).”

Middleton, however, did not respond to Agha’s signals, and told the Inquiry that he had not noticed them.

How did Middleton not notice? CCTV images of Middleton, available for all three exact times (at the request of Agha’s lawyer), show that he was staring straight out into a sparsely populated City Room. Presumably, he would have seen his own staff member, in a bright yellow top, repeatedly trying to attract his attention:

Source: Richplanet.net

Source: Richplanet.net

Source: Richplanet.net

Agha was in Middleton’s direct line of sight, at a distance of under 30 metres (both men were standing in front of their respective doors):

Source: Manchester Arena Inquiry (03:31:51)

Hall speculates that Middleton was aware of Agha but deliberately ignored him, so that Abedi would not be disturbed (35:20).

Having failed to attract Middleton’s attention, Agha walked a short distance to inform Kyle Lawler, who had a radio, of Wild’s report (§1.55). This was in keeping with his training. Agha told the Inquiry: “When someone raises a suspicion with yourself, you do have to report it to your nearest radio holder or your supervisor if you don’t have a radio yourself” (01:21:20).

Agha speaks with Lawler. Source: Richplanet.net

Lawler apparently “could not get through on the radio” (it is not specified to whom), he did not speak to Middleton, and he returned to his position on the footbridge (§1.55).

Thus, although Saunders finds that “Mohammed Agha should have done more immediately following his conversation with Christopher Wild” (§1.55), what else was Agha supposed to do? He had been instructed not to leave his post (and at the Inquiry expressed fear of losing his job if he did); his supervisor was apparently ignoring him; he did not have a radio; and even when he did report Wild’s concerns to a colleague with a radio, Lawler took no effective action (§1.57-1.59).

Therefore, was the hapless 19-year-old Agha scapegoated for Showsec’s failure to prevent the alleged attack? If the security services staged the attack, then crafting a “security failures” narrative would have been necessary to explain how the alleged terrorist got through. Such a narrative is also advantageous in making the case for more resources for the security services.

Darron Coster

Hall wryly remarks of McGuffie and Bradbury’s presence in a mostly empty City Room over half an hour before the end of the concert:

It’s clearly just coincidence that we have ex-military and ex-Counter Terrorism officers hanging around key positions at a teenage girls’ concert just before a surprise terrorist attack.

The coincidences continued to mount when Darron Coster entered the City Room within a minute or so of detonation. Ostensibly an ordinary member of the public coming to meet concertgoers, Coster just so happened to have served in a forensic capacity with the Royal Military Police for 22 years until 2008. As chance would have it, he was “familiar with the aftermath of a bomb explosion” (§16.180) and had battlefield first aid training, including applying tourniquets and applying pressure to wounds.

Coster’s immediate response was unlike that of an ordinary civilian: he immediately shut the City Room doors, because he did not want the public to see what was beyond the doors, was keen to preserve the crime scene, and did not want any potential shooters to have a line of sight into the room (§16.182).

At the Inquiry, Coster did not specify which doors he shut, nor is that information specified in the Inquiry report. However, we know from an interview that Coster gave to the Sun on May 28, 2017, that he is referring to the doors to the Arena concourse, through which Salman Abedi’s severed torso had supposedly been blown:

I sort of guessed it was a suicide bombing. Then I tried to close the doors because I could see the suicide bomber’s body.

I could see half of his body halfway inside. I went over and closed the doors because I didn’t want anyone seeing that.

It looked like he had been blown inside the doors. I didn’t want to look. His torso was through the doors and he had no legs.

At the Inquiry, Coster used the phrase “nobody needs to see that” (similar to “I didn’t want anyone seeing that”) in relation to “something” that was visible through the doors. We can infer from his Sun interview that the “something” was Abedi’s torso, although gory details were prohibited at the Inquiry.

We know that Coster’s account was fabricated, for the reasons given in relation to Inspector Michael Smith’s account of Abedi’s torso below. Coster had evidently learned of the torso’s supposed placement from the New York Times four days earlier and was fashioning his own story around it.

The Sun identifies Coster in a blurred version of the Parker photograph, which, however, shows some doors still open at or around 22:35, thus further undermining Coster’s account:

Source: The Sun

A fascinating feature of the Parker photograph is how difficult it is to identify anyone in it. For example, to my knowledge, no one has ever identified the man in Showsec uniform in the centre. Even though he can be seen in certain CCTV images, he is labelled by Operation Manteline as “unidentified” (could GMP not have forced Showsec to disclose his identity?). Similarly, for the three people other than Coster who are in civilian clothing and are apparently tending to those on the ground, who exactly are they?

Inspector Michael Smith

It is striking that everything about the emergency response conspired to hand Inspector Michael Smith effective control of the City Room. The fire service did not arrive for over two hours, only three paramedics entered the room before all the casualties had been evacuated, and there was no BTP Bronze Commander on the scene (see Part 9).

When asked at the Inquiry “Did you regard yourself as being the Bronze Commander for both GMP and BTP?,” Smith replied “yes” (01:08:30). He then confirmed that he gave instruction to Sergeant Hare (Tactical Aid Unit) and was commanding “about 30” officers in the City Room by 23:00. In other words, Smith was de facto in total operational command of the City Room.

Remember, too, that Smith appears to have been operating in splendid isolation from the other GMP commanders: not only did the Operational Firearms Commander, PC Edward Richardson, and the Force Duty Officer, Inspector Dale Sexton, not speak to him while in the City Room (§10.132, §13.159), but “no attempt was made by GMP strategic/gold or tactical/ silver command to obtain the views of Inspector Smith about the issue of safety in the City Room” (§13.399). The same was true of North West Ambulance Service (NWAS) Bronze Commander Daniel Smith, who not once thought to make the minute-long trip across the footbridge into the City Room to speak to his GMP counterpart about safety (§10.155, §14.232).

One could be forgiven for thinking that Inspector Smith was running an entirely separate operation from the other Commanders. Had they been ordered not to establish communication with him?

The police radio chatter from the night, which was leaked to Richard D. Hall, presumably by someone with GMP who suspected foul play, reveals that Smith made a very specific claim in real time (ca. 23:06 pm) about having discovered Salman Abedi’s body:

I think we may well have found our, er, our, er bomber. […] He’s very dead, completely, er, complete explosion on his body. There’s plenty of bolts and nuts and things around where he was. So, he’s actually outside Block 106 in the Arena foyer. […] I’ll seal the doors that are open, that’s probably where the explosion has gone in to there. (Timestamp 22:52)

Block 106. Snippet from Kerslake Report, Figure 3.

Did it really take 35 minutes (19 minutes after Smith first entered the City Room) before Abedi’s severed torso was discovered? Darron Coster claimed to have already sealed the doors so that Abedi’s torso could not be seen within minutes of the detonation (§16.182). Smith’s reference to “plenty of bolts and nuts and things” seems contrived. By “outside Block 106 in the Arena foyer,” did he mean in the Arena concourse, in the City Room, or somewhere in between?

Smith’s real-time account of discovering Abedi’s torso is demonstrably untrue. The area outside Block 106, for instance, is shown on the CCTV image below, captured at 22:40:29. It shows no severed torso.

Source: Richplanet.net

The Bickerstaff video was filmed outside Block 106, and there, no one in the background seems remotely concerned about a severed torso lying on the concourse floor (Davis, 2024, p. 236).

The “summary of footage” for the 22:49:46 CCTV image below states that

A large number of people have gathered at one of the entrances/exits from the Arena concourse into the City Room. This is the location GMP Inspector Michael Smith was seen walking towards a few moments ago.

Source: Richplanet.net

If Inspector Smith was already at that location at 22:49, why did he claim on police comms to have first discovered Abedi’s torso there at 23:06?

Nor was the torso located on the City Room side of those doors (for the location reported by the New York Times on May 24, 2017):

Source: The BBC’s Manchester — The Night of the Bomb (37:35)

Despite the lack of a torso in the concourse, PS Frederick Warburton’s witness statement indicates that he recalled

seeing something on the floor in the concourse eventually realising it was the remains of a body, the body of the attacker that had been blasted through the doors onto the concourse. [53]

Thus, we might wonder whether the “torso on the concourse” narrative was a wider GMP fabrication.

When asked over the radio where to set up a command post, Smith replied: “I don’t want any more in here who haven’t already been in here […] I don’t want anyone else coming in here now” (46:26). This is consistent with the idea of creating a controlled environment.

At the Inquiry, Smith was not asked about his claim on the police radio communications to have discovered Abedi’s body (22:52), and that information was omitted from the Inquiry report. Nor was Smith asked why he told the Control Room not to send anyone else into the City Room. Yet, other aspects of Smith’s radio communications on the night were asked about, such as his instruction to seal off the railway entrances and get NWAS staff into the City Room “as soon as” (§13.403). Did Operation Manteline only pass on certain sections of the police radio communications to the Inquiry?

There is no indication in the Inquiry report of what Smith did after midnight, when evidence of a crime scene was fabricated (see Part 10), but we know that he remained “at the scene” until after 04:00 (§13.433).

Ian Parry

Hall includes Ian Parry, the head of Emergency Training UK, on his schema alongside Showsec’s Middleton, Beak, and Perry as Arena staff potentially recruited by Counter Terrorism.

The evidence for this, however, is weaker than for those named above, not least because there are only two CCTV images available of Parry. The first, at 22:36:15, shows him on the Arena concourse heading towards the City Room. The second, at 22:36:31, shows him entering the City Room.

There is something odd about the 22:36:31 timestamp, however. For example, by comparing two images of the same location from the same CCTV camera at 22:04:20 and 22:36:31, respectively, Hall observes that there was smoke in the City Room when Parry entered:

Source: Hall, Manchester on Trial (28:34).

SMG Events Manager Miriam Stone was watching a CCTV monitor in the Sierra Control Room when, at 22:31, it went white, and “after a few seconds the monitors cleared. It was apparent to her that there was white smoke in the City Room” (§16.122). According to the Inquiry transcripts, “CCTV shows that at 22.31.05, as the smoke cleared after the explosion […]” (p. 7).

Did it really take over six and a half minutes for the smoke to clear, or did Parry enter the City Room before 22:36:31? It is possible that he entered almost straight away and that Operation Manteline officers changed the timestamp (cf. Part 12).

Another peculiarity relating to Parry arose when John Cooper QC asked BTP PC Danielle Ayers the following:

Q. One of the things you said in your statement, which you made on 22 July 2021, was that Ian Parry said to you […]: “An ambulance won’t be coming for her any time soon, so you might as well stop.” Do you remember him saying that?

A. Yes.

Q. […] And you say — this was in relation to Kelly Brewster: “I cannot recall anything more about the conversation other than me getting a little annoyed as I was thinking how he would know that no ambulance was coming.” (p. 47)

Ayers’ question was a good one. How did Parry know this?

In the Inquiry report, Parry is singled out for numerous criticisms, including: failing to make enquiries of emergency services personnel regarding the safety of the City Room for his staff (§16.36); holding out of date/expired qualifications (§16.45-16.46); employing underqualified staff (§16.50); not taking Major Incident table top exercises seriously (§16.65-16.67); failing to pass a METHANE (Major Incident) message to NWAS (§16.72); and failing to ensure that someone was acting in the EMTA (Emergency Technician Advanced) role (§16.94).

Most seriously, Parry had not adequately trained his staff in the application of tourniquets, which should been applied to John Atkinson’s legs, or haemostatic dressings, which should have been applied to his wounds. Atkinson officially died from his injuries.

Saunders finds that Parry “did not discharge his command role to an adequate standard” (§16.101) and that he was not a reliable witness during the Inquiry (§16.77).

We cannot be certain what Parry’s true role was on the night. We do know, however, that he and his family posed with Andy Burnham, possibly at the One Love Manchester concert in June 2017, which raised over £17 million for the Manchester Emergency Fund.

Source: X

Perhaps it was just a harmless photo op, but it does link Parry, like Bradbury, to Burnham, who would later be part of the push for two pieces of oppressive legislation off the back of the Manchester Arena incident, namely, Martyn’s Law and Eve’s Law.

Other ETUK Staff?

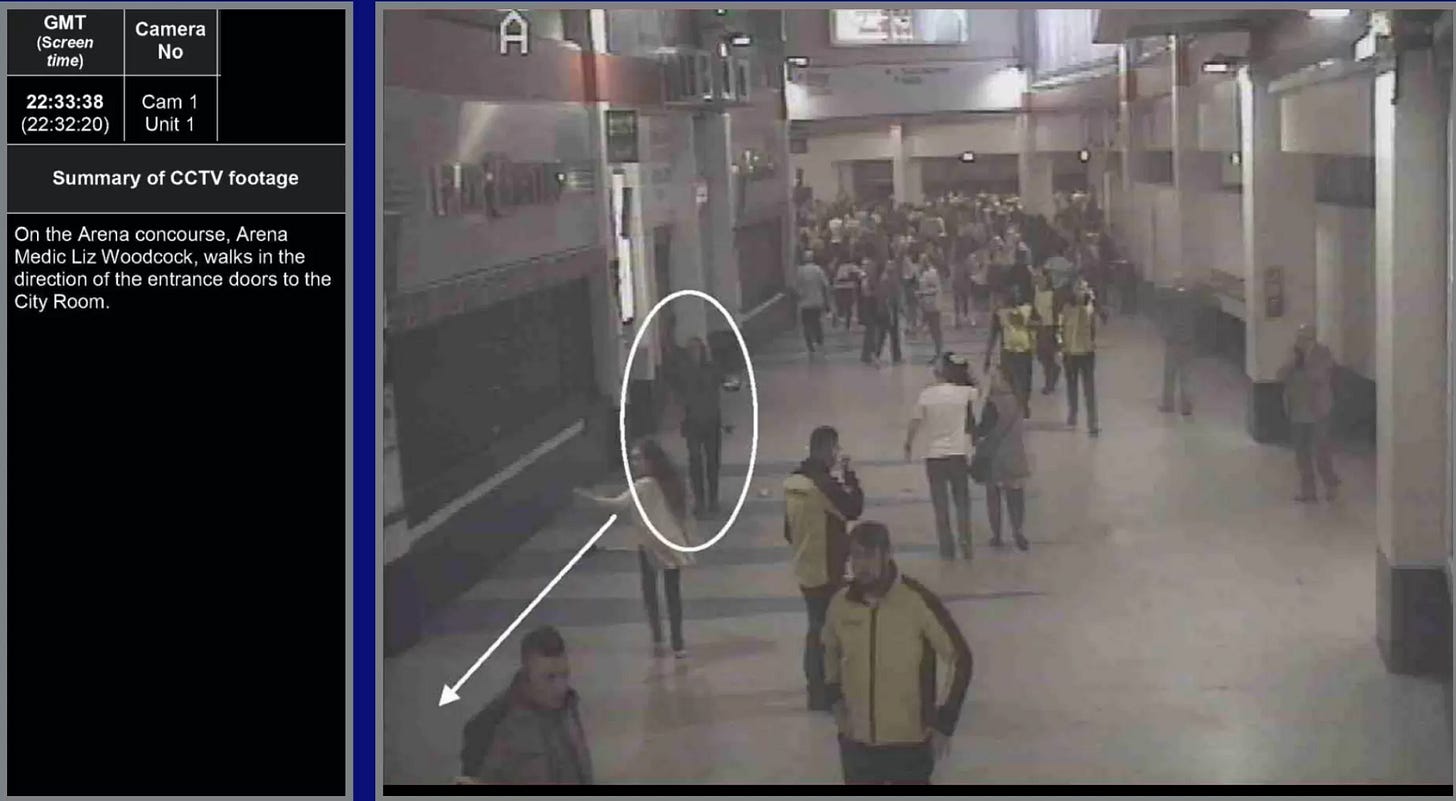

Sophie Cartwright QC told the Inquiry that “a large number of ETUK staff entered the City Room shortly after detonation” (02:17:10). Officially, the ten were: Liz Woodcock (at 22:34:35), Ian Parry (22:36:31), Marianne Gibson (22:40:30), Zack Warburton (22:40:24), Ken O’Conner (22:41:10), Craig Seddon (22:41:54), Ryan Billington (22:42:47), Kristina Deakin (22:45:02), Rabina Jones-Silly (after 22:45) and Sarah Jane Broadbent (after 22:45). Rabina Jones witness statement also places Jade Duxbury in the City Room [p. 3]).

Eight of those ETUK staff were on the scene within 14 minutes of the detonation — officially before Greater Manchester Police, NWAS, and Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service, although some British Transport Police officers also arrived within minutes. This makes ETUK by far and away the most important organisation when it comes to finding out what was going on in the City Room in the immediate aftermath of the detonation.

Yet, Operation Manteline showed no particular interest in ETUK’s actions in the City Room. Apart from the 22:36:31 image of Ian Parry mentioned above, the only other CCTV imagery of ETUK staff post-detonation shows Ryan Billington in the City Room (at 22:57:59, 23:05:30, and 23:11:44), nine ETUK staff exiting the City Room via the footbridge (23:51:31), plus some ETUK staff at the Casualty Clearing Station between 23:54:37 and 01:00:35.

Similarly, in terms of the Inquiry, only Parry, Billington, and Duxbury were initially called to give evidence — not about what they actually witnessed, but, rather, about protocols, training, following procedure on the night, etc. Liz Woodcock and Marianne Gibson were called later, in relation to their interactions with Saffie-Rose Roussos.

Instead of “hot tubbing” (the legal term for taking evidence from multiple witnesses simultaneously) all ten ETUK staff who were present in the City Room post-detonation, to find out exactly what was going on there, the Inquiry chose to ignore six of them and impose significant restrictions on what the other four were allowed to talk about. Why? Were the ETUK staff being shielded from effective scrutiny?

Joanne McSorley, a member of the public who present in the City Room at the moment of detonation, told the Inquiry

A woman, who I assume was some kind of first aider, dressed all in green, came over and told my mum to get down on the floor. (p. 23)

Because her mother was physically unable to do so, the woman told her she would have to leave. This all seems very peculiar. Why would ETUK be telling people to “get down on the floor” in the immediate aftermath?

If the Manchester Arena incident were an exercise run by the security services, as opposed to a real suicide bombing involving a massive TATP shrapnel bomb, then it stands to reason that ETUK staff must have known. Perhaps they, too, were sworn to silence under the Official Secrets Act.

At any rate, ETUK staff emerged from the City Room, the site of a reported bloodbath, with no blood on their uniforms at the end of the evening:

Source: Richplanet.net

As with Showsec, the ETUK employees did not give interviews after the event. An ETUK Facebook post from August 30, 2017, notes that “As a company and out of respect for the victims of the Manchester Bomb we have not taken part in any media stories.”

ETUK’s last company accounts were posted on November 30, 2016. Having been contracted to work at the Manchester Arena for well over a decade, it was reported that ETUK “dissolved a few months after the explosion.”

Conclusion

If, as Hall contends, the Manchester Arena incident were a staged event, with the City Room serving as a controlled and managed environment, then it follows that there must have been operatives present managing that environment.

Although nothing can be proved definitively, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that Salman Abedi, Martin McGuffie, Andrea Bradbury, Dave Middleton, Darron Coster, Inspector Michael Smith, and Ian Parry may all, in different ways, have been implicated in an intelligence operation. And that Mohammad Agha was an undeserving victim of that operation.

McGuffie (ex-military) and Bradbury (ex-Counter Terrorism) appear to have been handling Abedi. Had he failed to deliver in planting his device and making a getaway, then the entire operation, with dozens (Hall estimates over 100) people involved on the night, would have failed.

Although the City Room was quiet before 22:00, we know that Abedi was in position at 21:52, that McGuffie was sitting reading his book at that time, and that Bradbury, Middleton, and other Showsec staff had just gathered at the doors to the concourse:

Source: Richplanet.net

If this was a staged event, then the Arena staff who were first on the scene, i.e., Showsec and Emergency Training UK, must have been co-opted. There is evidence that Middleton’s Showsec team may have helped to secure the City Room pre-detonation. It is not credible that staff from both organisations attended the scene shown in the Barr footage and Parker photograph and failed to notice anything suspicious. Both organisations maintained a low profile after the event.

Meanwhile, with firearms officers guarding the doors, possibly within a minute or two of detonation (see Part 10), Inspector Michael Smith effectively assumed total operational command within the City Room. Praised to the skies by the Inquiry report, we know from leaked police radio communications (timestamp 22:52) that Smith made a demonstrably false claim in real time about having discovered Abedi’s body through the doors to the Arena concourse, a lie that was repeated by the New York Times and Darron Coster.

Not only those who were actively recruited into the intelligence operation would have known what really took place in the City Room that night. So too would dozens of other people who were present.

For example, we know the identities of at least 111 uninjured people who were present in the City Room post-detonation and who therefore witnessed the crime scene first-hand. As identified on CCTV and in the Inquiry report in the post-detonation period up to 00:58:47, they are:

GMP staff: Inspector McDonald, PS Corrigan, Inspector Hawksley, PC Ho-McKenna, PC Owen Whittell, Firearms Officer PS Lee Sharples, PS James McGowan, PS Linney, Sergeant Kam Hare, DI Neil Hayward, DI Natalie Dalby, DC Donna Haldane, CI Mark Dexter, Inspector Michael Smith, DS Denise Worth, Sergeant Anwyl (p. 33), bomb scene manager Robert Gallagher (§23.135), PC Lauren Moore (§17.99), PC Leon McLaughlin (p. 74), PC Hill and PC Ball (p. 76), PC Michelle Johnson (p. 77), PC Anthony Sivori (p. 10), PC Chelsea Meaney (p. 20), Special Constable Michael Dalton (p. 30), and PS Martin Dunn (p. 3). Special Sergeant Jared Simpson was reportedly “one of the first GMP officers on the scene of the arena attack” and was awarded a British Empire Medal, although he did not feature in the Inquiry. Off-duty PC Michael Buckley was waiting in his car for his daughter and was awarded the Queen’s Policing Medal for rushing to the City Room to help [§16.188])

NWAS paramedics: Chris Hargreaves, Lea Vaughan, Patrick Ennis, and Ian Devine;

Travel Safe officers: Phillip Clegg, Niall Pentony, and Reece McKay (§16.146);

BTP staff: PC Jessica Bullough (§13.44), PCSO Mark Renshaw, PCSO Lewis Brown, PC Matthew Martin, dog handler PC Philip Healy, PS Wildridge, PC Jane Bridgewater (p. 48), PS John Whitaker (§13.44), PC Simon Trow (§13.45), Medic PC Ben Davidson (§13.46), PC Stephen Corke (§13.47), PC Thomas Campbell (§13.48), PCSO Jon Paul Morrey (§13.48), DS Christopher Broad (§13.48), PC Mark Emberton (§13.48), PC Dale Edwards (§13.48), PC Michelle Johnson (§13.48), PC Danielle Ayers (§13.49), PC Richard Melling (§13.49), PC Lee Owen (§13.49), PS Peter Wilcock (§13.51), temporary DC Mark Haviland (§13.51), PC Lewis Adams (§13.329), CI Andrea Graham, PC Mark Conway (p. 6), and an unidentified Crime Scene Examiner (possibly CI Peter Kooper, who attended with PS Brian Dickinson);

ETUK staff: Ian Parry and Ryan Billington, plus six others mentioned by Sophie Cartwright QC (02:17:10), namely, Liz Woodcock, Marianne Gibson, Zack Warburton, Ken O’Conner, Craig Seddon, Kristina Deakin, Rabina Jones-Silly, and Sarah Jane Broadbent;

Northern Rail staff: Stuart Craig (§16.157), Owen Sanderson and Steven Hawksworth (§16.160), Andrew Lowe (p. 2), and Barry Chaudry, Luke Westall, Ian Johnson, and Matthew Greenhalgh (p. 4; §16.162);

Members of the public present in the City Room at 22:31:00: Jonathan Woods (§16.166), Michael Bryne (§16.167), Ronald and Lesley Blake (§16.168), Philip and Kim Dick (§16.171-16.172), Jolene Smith (p. 6), Thomas McCallum, and NCP employee Martin Kay (p. 74). To this we should add John Barr and his son, as well as Chris Parker. Paul Clarke is named as present “shortly before the explosion” (p. 8)

Members of the public who went to the City Room to help: Bethany Crook (§16.173-16.175), Daren Buckley (“The CCTV showed he was in there for over 21 minutes”) and his son [§16.178-16179]), Darron Coster (deceased), Gareth Chapman (§16.186-16.187), Paul Reid (§16.189), Robert Grew (§16.190-16.192), Sean Gardner (§16.193; p. 29), Daniel Cooper (p. 31), and Thomas Owen (§16.194).

Martin McGuffie claimed at the Inquiry to have been waiting for two family members, but is not seen on CCTV post-detonation and is not mentioned in the Inquiry report;

Showsec staff: Daniel Perry (§16.135), Megan Balmer (§16.140), Usman Ahmed (§16.144), Jade Samuels (§16.144), and Akeel Butt (§16.144). Dave Middleton (§16.135) and Jordan Beak (§16.137) were allegedly affected by the detonation but recovered quickly enough to help immediately seal off the City Room. Mohammad Agha is not specified as having been injured in the Inquiry report, despite appearing on CCTV one second before detonation;

SMG staff: Jacqueline Day (p. 14);

Those present in the City Room at 12:27pm on May 23, 2017: Home Office pathologist Dr Philip Lumb, his colleagues Dr Naomi Carter and Dr Charles Wilson, DCI Terry Crompton, and coroner Nigel Meadows (00:28:30-00:32:27).

Present in the City Room on May 23 and 24, 2017: Lorna Hills (née Philp) plus two of her laboratory colleagues (p. 102).

If there are any real investigative journalists left in the UK, then there is no shortage of people whom they might like to interview. Note that the above list does not include reported victims or their families, and is not intended to be exhaustive.

At any rate, given the very serious questions that arise in relation to the events of May 22, 2017, it is essential that investigative journalists are not deterred by the show trial of Richard D. Hall and keep the spotlight on exposing what really took place.

Thank you for this careful analysis. The compilation and ordering of the CCT footage/ imagery assembled by Hall really is very impressive indeed. It leaves no doubt that there was no shrapnel bomb as the inquiry wants people to believe. I just wonder how people can live with their consciences when they participate in a mass deception like this. What ‘greater good’ can they possibly think there are serving. Or are they just all devoid of any ethical / moral fibre, paid or rewarded in other ways to keep silent by a cynical deep state?

Dear David: Congratulations on this excellent addition to your series of articles about the Richard D. Hall case. I’m glad that you included Mr. Hall’s wry remark about McGuffie and Bradbury’s presence “at a teenage girls’ concert just before a surprise terrorist attack.” This touch of subtle humor creates a refreshing pause in a grim narrative and thereby provides your readers with psychological fortification to proceed to the finish.

Speaking of humor, you might get a chuckle of out a few of my observations with regard to British English.

I have pondered the use, in your prose, of the phrases “in hospital” and “in the hospital” — as you comfortably switch back and forth between them as only a Briton can! As you probably know (though you may not have paid much attention to it), here in the States the phrase “in hospital” does not exit. Nor do we use the phrase “going to hospital” (as you do in this article).

In the American idiom, we always place an article before the word “hospital,” regardless of the context.

In the States, our closest equivalent to the British phrase “in hospital” would be “hospitalized,” But the word is not used frequently to indicate what Britons mean when they say that someone is “in hospital.” We Americans just say “in the hospital.” And, yes, if we’ve been to visit someone who is hospitalized, we also say we have been “in the hospital” (meaning a *specific* medical facility).

Arguably, our idiosyncrasy in this regard makes no sense. After all, we Americans use both the phrases “in school” and “in the school” — and understand the difference in meaning.

So maybe Henry Higgins is on to something when, in “My Fair Lady,” he sings a song about the English language and scoffingly observes: “In America, they haven’t used it for years!”

But what would Henry Higgins say about your use, in this article, of the phrase “go hospital”? My online search for the phrase fails to turn up any reference to it as being representative of British English. So is “go hospital” a typographical error?

In closing, I’ll tell you that this article has provided me with my first-time encounter with something called a “garden strimmer.” Indeed, according to one online article, the term is one that “we have yet to see in the US.” Here it is. If you scroll down to “Key Finding #6,” you’ll find a funny depiction of 1770s Redcoats arguing with American colonial rebels about the issue. See: https://bit.ly/40cHZCK. Best wishes, P.A.